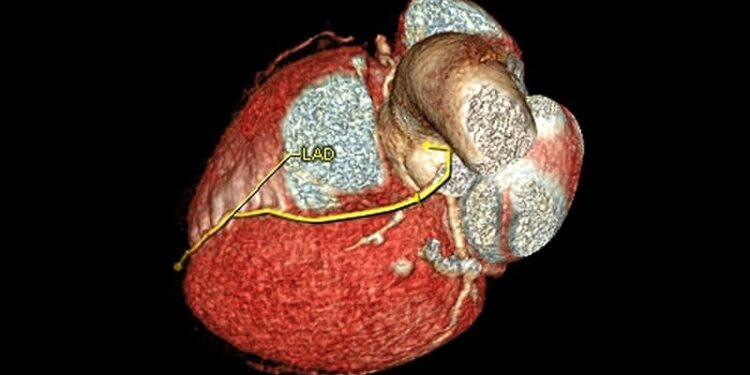

People with intermediate-risk scores on coronary artery calcium testing who received statins and intensive health coaching experienced less progression of arterial plaque and lower cholesterol levels after 3 years compared with people with similar calcium scores who did not receive a statin, researchers have found.

Previous research suggests that coronary artery calcium testing can detect subclinical atherosclerosis early enough to encourage lifestyle changes that lower cardiac risk, and that providing visual evidence of calcification improves lifestyle choices. The randomized clinical trial, which enrolled Australian adults aged 40-70 years, was published earlier this month in JAMA.

“It’s not simply a test of an imaging tool; it’s a test of a strategy,” said Thomas Marwick, MBBS, PhD, MPH, head of imaging at the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne and senior author on the study. The nurse-led intervention increased rates of adherence to statin therapy, Marwick said.

“This study really needed to be done. Being informed about risk — not only do you have risk, but you have early signs of disease — really helps with patient empowerment,” said Anita Kelkar, MD, a preventive cardiologist with the W.G. (Bill) Hefner Salisbury Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Kernersville, North Carolina. Kelkar was not involved in the study.

Lower Cholesterol, Less Plaque

Participants in the CAUGHT-CAD trial were at intermediate risk for developing coronary artery disease based on Australian risk calculators and a family history of premature cardiovascular problems. Of the 1091 people recruited to the trial, none was eligible to receive statins per Australian guidelines.

Coronary artery calcium scans were conducted on all participants. Then, 591 people were excluded because their score was 0; 30 people were excluded because their score was above 400, putting them at high risk for coronary artery disease; and another 12 withdrew consent.

Poor image quality excluded more participants, leaving 365 people for final analysis. This group included 179 people who received 40 mg of atorvastatin per day plus intensive health coaching and regular follow-ups from a nurse, which included viewing their calcium scans, and 186 patients with similar calcium scores who did not start statin therapy, received only cursory health education, and did not see their calcium scans.

All participants underwent coronary computed tomography angiography at baseline and after 3 years, along with cholesterol screenings. After 3 years, the people who received the statin plus health coaching had lower plaque volume than those not taking the drugs, and their cholesterol levels had declined.

“We have evidence that taking a statin will slow the progression of plaque,” in intermediate risk patients, said Puja K. Mehta, MD, with the Division of Cardiology at Emory University and director of Women’s Translational Cardiovascular Research in Atlanta.

Seeing evidence of calcification in one’s own arteries is compelling, Mehta added. “It really helps the patient; it’s the power of seeing something,” she said.

Michael Blaha, MD, a cardiologist at the Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Baltimore, wrote an editorial lauding the results of CAUGHT-CAD.

“If you take a relatively low-risk, healthy patient and say, ‘I think you should take a statin,’ they usually give a little bit of pushback. We know that continuation rates are as low as 50% at one year,” Blaha said, adding that the results of CAUGHT-CAD suggest that boosting adherence is possible.

Blaha called for greater insurance coverage of calcium imaging, noting that people sometimes pay for the test out-of-pocket. Although cost is not necessarily a deterrent (Blaha said Johns Hopkins charges $75 for a scan), he said adding the testing to insurance coverage would probably increase uptake by physicians who may hesitate to order the test if insurance coverage for their patient is not available.

“One of the drawbacks of the coronary artery calcium score is it detects calcified plaque; it doesn’t detect soft plaque. A lot of people, especially women, die from soft plaque eruption,” Kelkar said. Coronary CT angiography can detect soft plaque, Kelkar said, but that test exposes patients to more radiation than coronary calcium tests and is often not covered by insurance.

Despite the drawbacks of assessing coronary artery calcium, Kelkar said she believes the benefits of the test warrant wider use.

“There’s so much underdiagnosis of heart diseases in women, they may not experience chest pain or arm pain,” Kelkar said. “Even if the coronary artery calcium score does not detect soft plaque, using it can still help some women get treatment who would otherwise be dismissed,” Kelkar said.

Still, at least one cardiologist is skeptical.

“Plaque imaging is a surrogate measure of coronary artery disease. It’s difficult to measure, as evidence by exclusion of 13% of individuals excluded because of technical imaging issues,” wrote John Mandrola, MD, a cardiologist at Baptist Health in Louisville, Kentucky, and a contributor to Medscape, in a recent blog post about the trial.

Blaha reports advisory relationships with Novo Nordisk, Bayer, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Agepha, Vectura, New Amsterdam, Genentech, and Idorsia. Kelkar is medical director for Ventricle Health, which offers remote patient management in cardiology. Marwick and Mehta reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Marcus A. Banks, MA, is a journalist based near New York City who covers health news with a focus on new cancer research. His work appears in Medscape, Cancer Today, The Scientist, Gastroenterology & Endoscopy News, Slate, TCTMD, and Spectrum.

Source link : https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/cac-scans-statins-and-coaching-can-lower-plaque-volume-does-2025a100069l?src=rss

Author :

Publish date : 2025-03-14 19:46:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.