Philippa RoxbyHealth reporter

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAction is needed now to reduce ultra-processed food (UPF) in diets worldwide because of their threat to health, say international experts in a global review of research.

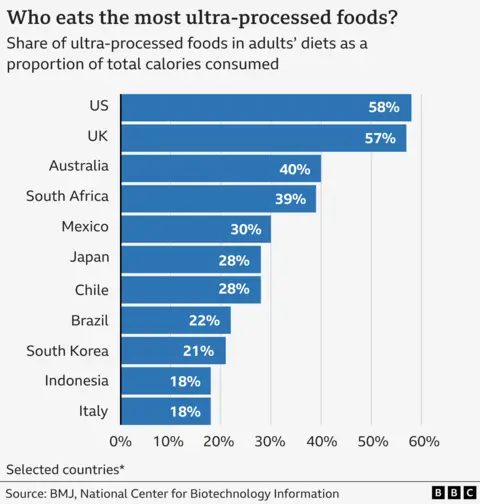

They say the way we eat is changing – with a move away from fresh, whole foods to cheap, highly-processed meals – which is increasing our risk of a range of chronic diseases, including obesity and depression.

Writing in The Lancet, the researchers say governments need “to step up” and introduce warnings and higher taxes on UPF products, to help fund access to more nutritious foods.

However some scientists say this review can not prove that UPFs directly cause health harms and more research and trials are needed to show that.

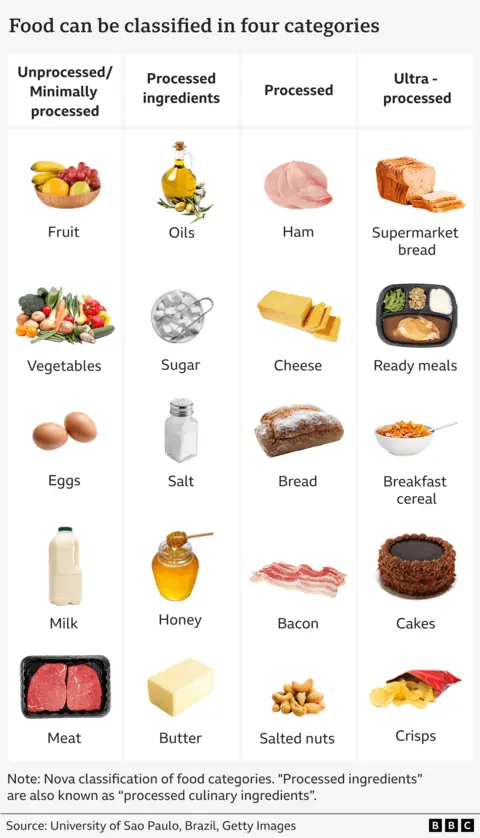

Ultra-processed foods are defined as containing more than five ingredients which you would not find at home in your kitchen cupboard, such as emulsifiers, preservatives, additives, dyes and sweeteners.

Examples of UPFs include sausages, crisps, pastries, biscuits, instant soups, fizzy drinks, ice cream and supermarket bread.

Surveys indicate these industrially-manufactured foods are on the rise in diets around the world, worsening the quality of what we eat with too much sugar and unhealthy fats and a lack of fibre and protein.

This review of evidence on the impact of UPFs on health, carried out by 43 global experts and based on 104 long-term studies, suggests these foods are linked to a greater risk of 12 health conditions.

These include type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, depression and dying prematurely from any cause.

Review author Prof Carlos Monteiro, from the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil, who set up the Nova classification system for categorising food, said the growing consumption of ultra-processed foods “is reshaping diets worldwide, displacing fresh and minimally processed foods and meals”.

“This change in what people eat is fuelled by powerful global corporations who generate huge profits by prioritising ultra-processed products, supported by extensive marketing and political lobbying to stop effective public health policies to support healthy eating,” he added.

Co-author Dr Phillip Baker, from the University of Sydney, said the answer was “a strong global public health response – like the coordinated efforts to challenge the tobacco industry”.

The review acknowledges a lack of clinical trials showing exactly how UPFs damage health – but says that should not delay action to protect people worldwide from potential health harms.

Some scientists have commented that it is difficult to untangle the effects of UPFs in people’s diets from other factors in people’s lives, such as lifestyle, behaviour and wealth.

Critics of the Nova classification system say it relies too much on the level of processing in foods, and not on how nutritious that particular food is. For example, wholegrain bread, breakfast cereals, low-fat yoghurts, baby formula milk and fish fingers all count as ultra-processed but have lots of good in them.

Prof Kevin McConway, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University, said: “A study like this can find a correlation, but it can’t be certain about cause and effect.”

He said there was still “room for doubt and for clarification from further research”.

“It seems to me likely that at least some UPFs could cause increases in the risk of some chronic diseases. But this certainly doesn’t establish that all UPFs increase disease risk.”

It is still not clear what it is about ultra-processed foods that could be causing or contributing to diseases.

Prof Jules Griffin, from the University of Aberdeen, said there were some positive sides to food processing, and more research to understand how it influences our health was “urgently needed”.

The Food and Drink Federation says UPFs can form part of a balanced diet, like frozen peas and wholemeal bread.

“Companies have been making a series of changes over many years to make the food and drink we all buy healthier, in line with government guidelines,” says Kate Halliwell, chief scientific officer at the Food and Drink Federation, which represents industry.

The amount of sugar and salt in products on sale in shops and supermarkets has gone down by a third since 2015, she added.

Current UK government advice on diet is to eat more fruit, vegetables and fibre, and cut back on sugar, fat and salt.

Source link : https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cy4pjjzd784o?at_medium=RSS&at_campaign=rss

Author :

Publish date : 2025-11-19 12:53:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.