Christopher Chiu conducted the first human challenge trial for covid-19 in 2021

Thomas Angus/Imperial College London

At first glance, you would think it was a modest hotel. There are en-suite bedrooms, a socialising area with table tennis and pool tables and even on-call staff. Despite appearances though, this unassuming glass-fronted building on the outskirts of Antwerp, Belgium, isn’t a place where people come to rest their heads ahead of a day’s sightseeing. Instead, inside, healthy volunteers are swallowing virus-laced drinks, being sprayed with pathogens and waiting to deliberately fall ill.

Welcome to Vaccinopolis, a €20-million facility built by the University of Antwerp for a singular purpose: to infect people with diseases. The building, completed in 2022, specialises in running “human challenge trials”, experiments in which small groups of volunteers are exposed to diseases under tightly controlled conditions with the aim of fast-tracking vaccine development and monitoring infections as they unfold in real time.

Deliberately infecting people with nasty diseases in the name of science isn’t a new idea: human challenge trials have helped us understand and treat diseases such as typhoid for decades. But they have long existed on the margins because they were too rarely used for most researchers to be aware of them, as well as due to ethical concerns. Now, that’s beginning to shift. The urgency of the covid-19 pandemic adjusted the calculus of many scientists and policy-makers, bringing fresh attention to the idea of challenging people with some of the world’s most persistent pathogens and diseases, like norovirus and malaria.

The draw of these trials is speed. Their design allows scientists to test a candidate vaccine with a fraction of the participants of conventional trials and often in a matter of weeks. Now, with bespoke centres like Vaccinopolis facilitating such research, far more people are getting sick on purpose in the hope of speed-running new treatments.

Tackling persistent diseases

There is a long history of scientists deliberately infecting people in the name of progress. Edward Jenner famously developed the first smallpox vaccine after purposefully infecting a young boy with cowpox and then repeatedly exposing him to smallpox to create immunity. But such history includes much darker episodes. During the second world war, German and Japanese researchers used prisoners of war as test subjects, infecting them with diseases like tuberculosis and plague. Many of them died.

Against this backdrop, as well as amid fears of causing long-term damage to participants, human challenge trials have seemed troubling. The covid-19 pandemic – with its grim death toll and rampant economic damage – shifted the conversation, however. “There’s been a step change in the recognition that these studies have value and can be ethically acceptable,” says Christopher Chiu, an infectious disease researcher at Imperial College London. “I think any doubt about that has largely disappeared.” In 2021, he led the world’s first covid-19 challenge trial, in which he exposed 36 healthy volunteers between the ages of 18 and 30 to the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus.

Challenge trial volunteers are deliberately exposed to a controlled dose of a pathogen

Guido Mieth/Getty Images

Eighteen developed an infection and were closely monitored for four weeks. The study yielded invaluable insights, showing that even low doses of the virus can cause infection, but that younger people were more likely to have milder symptoms. Chiu is now leading a new project that will test the next generation of covid-19 vaccines, with trials scheduled to begin by the end of the year. “We are trying to accelerate the development of vaccines which stop infection completely and therefore stop transmission,” he says.

And it isn’t just covid-19. These trials are increasingly being used to test cutting-edge vaccines against some of humanity’s most enduring pathogens. Take norovirus, the notorious winter-vomiting stomach bug. It kills about 200,000 people a year and mutates fast enough to outpace the immune system, making it a tough target for vaccines. Earlier this year, scientists at San Francisco biotech firm Vaxart decided to try a new approach to working out a vaccine’s efficacy. In a clinical trial, more than 100 volunteers were asked to drink norovirus-laced shakes. About half had been given a tablet of the company’s experimental vaccine a month earlier.

By tracking who got ill, and how severely, scientists were able to assess how well the protective pill worked in just over a week. The results were promising. Vaccinated volunteers showed milder symptoms and shed less virus from both ends of their digestive tract, suggesting the vaccine could both protect individuals and reduce transmission.

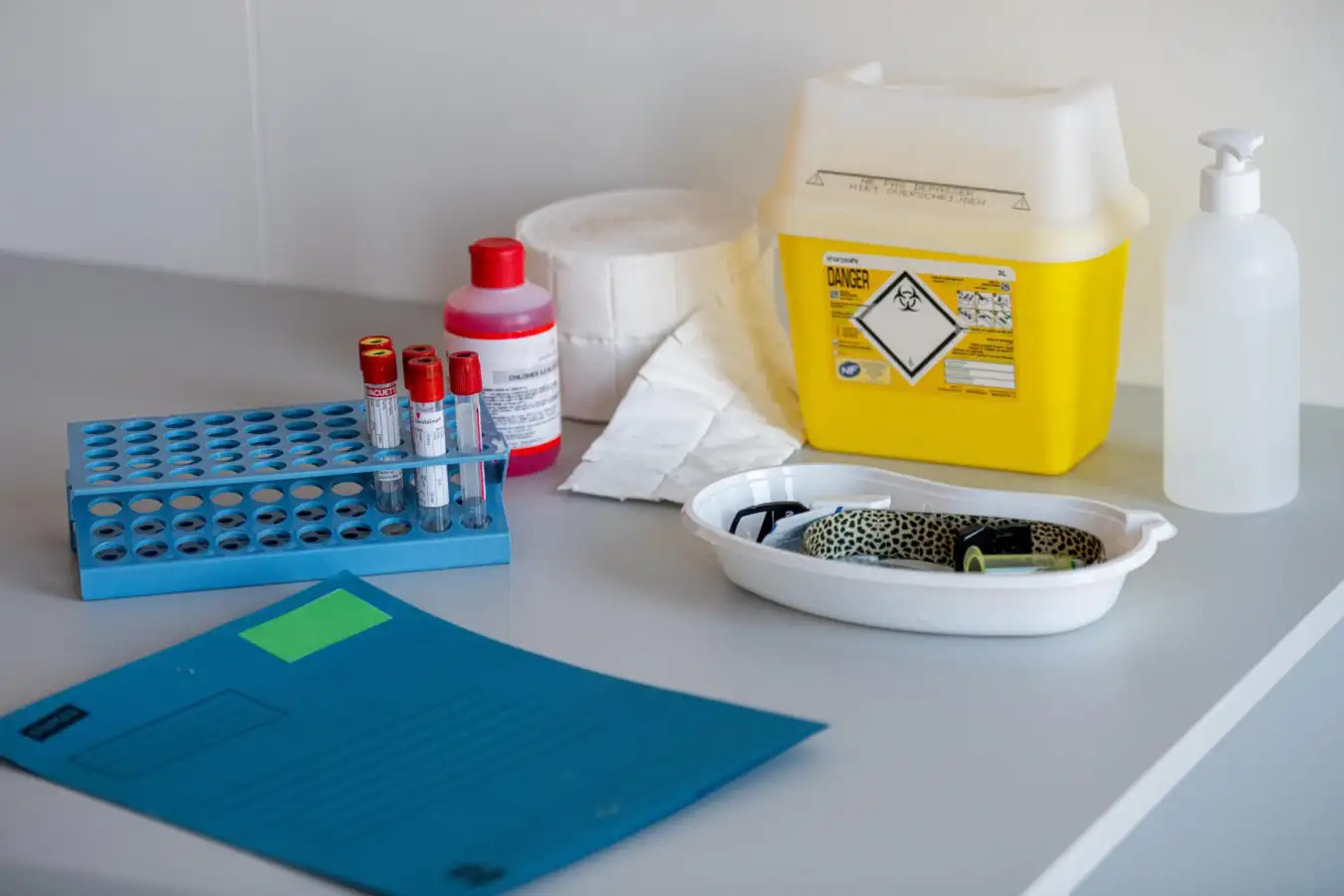

Human challenge trials allow scientists to collect samples from infected participants to track disease progression

JONAS ROOSENS/Belga News Agency/Alamy

Collecting this sort of data in such a short amount of time sounds especially impressive if you contrast it with the timelines of conventional vaccine trials. These require large numbers of participants in the hope that enough people will naturally contract the disease to generate statistically meaningful comparisons between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups. That can be a problem when the infection rates are naturally low, as was the case in past Ebola outbreaks. Often, so few people caught the virus that vaccines couldn’t be effectively tested – not because they didn’t work, but because there weren’t enough cases to prove that they did.

By controlling who gets infected, challenge trials sidestep this issue, with far fewer participants needed to get early answers. While challenge trials won’t replace large-scale clinical trials entirely – regulators will still want to see real-world results at scale – they help researchers prioritise which vaccine candidates are worth pushing forward. Both currently approved malaria vaccines were identified in these kinds of challenge studies, says Chiu, before progressing to broader trials.

But speed isn’t the only advantage of challenge trials. Because participants are infected in carefully controlled settings, with researchers able to dose a participant with exact amounts of a pathogen, tracking a disease from the moment it takes hold becomes possible. That level of detail offers a window into how pathogens behave and how the body responds, paving the way for future treatments and offering the potential to shape public health policy.

Vaccinopolis

That’s the promise of Vaccinopolis, the residential quarantine facility in Antwerp built to host human challenge trials. The facility has 30 private bedrooms, each with a bathroom, fridge and microwave and is equipped to test pathogens up to biosafety level 3, the category that includes the coronavirus, as well as the nasties responsible for plague and tuberculosis. While participants in trials involving those sorts of diseases will be confined to their air-filtered, negative-pressure rooms, during tests of less dangerous diseases, such as influenza, they will be able to mix in social areas, provided they wear masks to avoid influencing each other’s immune responses.

Vaccinopolis is dedicated to testing vaccines against diseases like influenza, strep and malaria

JONAS ROOSENS/Belga News Agency/Alamy

This more relaxed approach awaits volunteers in mid-2026, when Vaccinopolis will host a study on how influenza spreads, part of the effort to sharpen our tools and understanding before the next pandemic threat emerges. Pierre Van Damme at the University of Antwerp is the research centre’s director. In the upcoming flu study, his team will focus on a localised response called mucosal immunity – the body’s front line of defence in the nose, throat and lungs against airborne pathogens. Van Damme and others think that boosting this initial immune response could be the best way to develop vaccines that not only prevent illness, but also block further transmission.

Conventional vaccines train the immune system to stop people from falling ill, but that doesn’t mean they prevent the spread of infection. A vaccinated person may still carry and transmit the disease to others, even while they don’t show symptoms themselves, something the anti-vaccine movement used to falsely claim that covid-19 vaccines were ineffective. Mucosal vaccines, usually delivered via nasal spray or oral tablets, take a different tack, aiming to trigger immune responses in the common entry points for bacteria and viruses. Stop a pathogen there, and you may prevent both illness and its onward spread.

“Then I think we are really moving to vaccinology 2.0,” says Van Damme. “You open a completely new dimension because herd immunity will then be obtained much more easily.” Human challenge trials are, for now, the only way to study mucosal immunity with the precision required to track the subtle immune responses involved, he says. “This is the first step to better understand mucosal immunity in a controlled situation.” Several mucosal covid-19 vaccines have already been approved in countries including China, India and Russia. But so far, there is little data on whether they block transmission. That’s what Chiu hopes to find out in his new challenge trial. “We’ve asked for developers to come to us with their vaccine candidates, which we will test,” he says. “We’ll try and show they do a better job at preventing infection and transmission than the injected vaccines.”

Getting sick for science

If the idea of coming down with a horrible infection while physically isolated from everyone you know and love doesn’t have you gagging to join a challenge trial, you wouldn’t be alone. Learning to select the right volunteers is something Van Damme and his team have picked up from previous trials. Attitude is key. “What is important is that the people complain as little as possible,” he says.

One such candidate is Jake Eberts, who joined a 2022 challenge trial run in a dormitory by the University of Maryland to test a vaccine against Shigella, a bacterium that causes dysentery. “The idea sounded a little bit nuts to me. It sounded medieval,” says Eberts, now a consultant based in Washington DC. But Eberts says he was motivated to join anyway for the chance to move the needle on a disease that takes 600,000 lives every year, with the highest incidence among children under the age of 5.

“I was a guy born in Texas in a clean, safe hospital who never had to worry about the dozens and dozens of horrible, horrible diseases that regularly plague children across the world,” says Eberts. The money he got as compensation for joining the study – $7350 – also helped make the decision easier. “I’m not Mother Teresa. I would not have done this for free,” he says.

A month after receiving a shot of either a vaccine or a placebo – he still doesn’t know which – Eberts was called into the isolation facility with about 15 other volunteers and given a glass of Shigella solution to drink. “Then for the next day or two, it was like Chekhov’s gun was hanging on the wall and I was just waiting for it to fire,” he says. Bang. “It hit me at midnight on a Friday,” he says. “I was one of the sickest in the cohort. The doctor told me I was a real overachiever.” Once the illness was confirmed the following day, Eberts was given antibiotics and rehydration, and by Monday, he was fine and working remotely. He was discharged two days later.

As brutal as his experience was, Eberts says he is very aware that it was nothing compared with what most of the 165 million people who contract Shigella infections each year worldwide go through. Eighteen months later, he volunteered again, this time for a Zika challenge trial. “Zika was much more chill than dysentery,” he says. “I did try to do a third, for malaria, but that was cancelled.”

“

I kind of had won that cosmic lottery and it felt good to give back

“

The results from his Shigella vaccine challenge trial were published last year. The vaccine showed modest benefits: diarrhoea rates dropped from 82 to 68 per cent, and fever from 68 to 55 per cent. The biggest effect was against severe symptoms of dysentery, such as diarrhoea combined with other symptoms like fever, nausea or pain, with a reduction from 55 to 18 per cent. The vaccine is still being investigated and was recently tested in a field trial in Kenya, including in 200 infants under the age of 1.

Challenge trials are designed to minimise the risk to volunteers like Eberts: short-term effects only and a guaranteed “rescue” treatment that can halt the disease if participants get too sick. But not all pathogens are considered suitable. In 2017, ethicists blocked a proposed Zika trial on the basis of “concerns that it could cause lasting paralysis or be transmitted unknowingly to sexual partners.” By the time of Eberts’s Zika trial, the risk of men with the virus infecting their sexual partners was considered to be lower, although he and other participants were still told to abstain from sex or to use protection for several weeks afterwards.

The line between acceptable and unacceptable risk remains central to how future human challenge trials will be run. Unlike conventional trials, volunteers often receive no direct benefit to their health. They may not be at risk from an ongoing outbreak, or may not be sick and hoping for a cure. Indeed, some ethicists remain uneasy. Charles Weijer at Western University in Canada argues that early covid-19 challenge trials ignored long-term uncertainties, including the risk of long covid. “There are important ethical constraints on challenge studies, and I think that in the context of covid-19, people were just not paying attention to those constraints,” he says. “There was virus everywhere, so doing big field trials was actually really straightforward.”

Chiu disagrees, saying that with so much transmission already happening in the UK, most volunteers would have become infected at some point anyway. Follow-up studies also showed long-term effects were rare for the young, healthy people who volunteered. In Chiu’s covid-19 trial, the only lasting complication reported was a single case of loss of sense of smell, which was later recovered. Like Eberts, volunteers were paid for their time, to the tune of £4500. That might sound like a lot, but given they spent up to 16 days in quarantine, it works out at less than £12 per hour.

“I do think it’s appropriate to compensate people for their time,” says Weijer. “Generally speaking, that’s benchmarked at something like minimum wage.” Incentives to keep bringing in the volunteers needed to power these trials are crucial. A database of trials maintained by 1 Day Sooner, a US-based research advocacy group, shows more than 60 ongoing or planned challenge studies aimed at developing potential treatments for diseases like gonorrhoea and yellow fever, as well as tropical parasites like the whipworm and hookworm.

Still, Eberts maintains that altruism is his biggest motivator. “I kind of had won [the] cosmic lottery and it felt good to give back.”

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2505159-how-deliberately-giving-people-illnesses-is-supercharging-medicine/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-12-03 16:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.