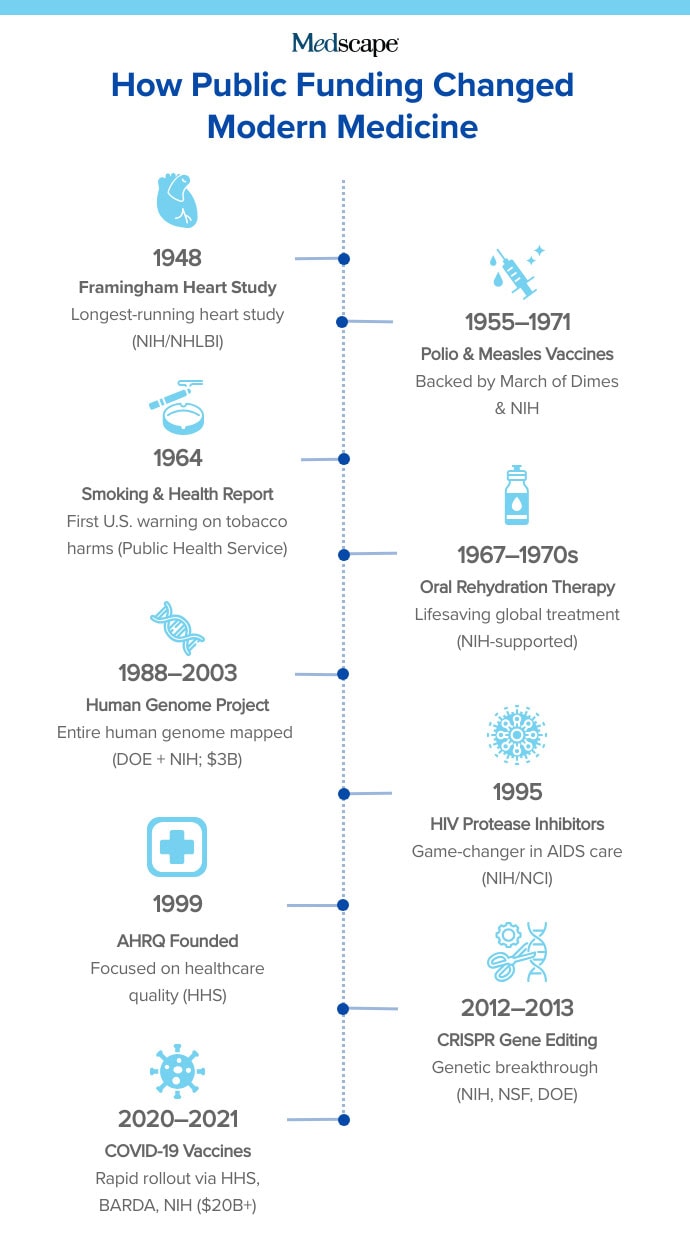

Since World War II, a quiet partnership between the US government and academic researchers has helped shape the course of modern medicine. Public funding has underwritten discoveries that changed how we detect, treat, and prevent disease — sometimes in ways that were barely imaginable when the research began.

This relationship traces its roots to the 1945 report Science, The Endless Frontier, written by Vannevar Bush, who was then the head of the wartime Office of Scientific Research and Development. Bush argued that continued investment in basic research — the kind driven by curiosity, not short-term profit — was essential not only for national security but also for public health and economic growth.

“Basic research is the pacemaker of technological progress,” Bush wrote. His report helped shape the creation of the National Science Foundation and guided peacetime funding efforts at agencies like the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which would go on to support generations of US scientists.

In 2023, the federal government spent nearly $200 billion on research and development (R&D), much of it through NIH and other science-focused agencies. That money supports everything from molecular biology to drug development to health data infrastructure, often with payoffs that take decades to emerge. But this investment model is now under threat. The Trump administration’s proposed 2026 federal budget calls for sharp reductions in R&D spending, including 40% less for NIH (though a Senate committee has rejected that proposal, calling instead for an increase in funding for the NIH for next year). Experts warn this could impede medical breakthroughs, slow the development of new treatments, and increase the burden of preventable disease.

“It’s hard to even comprehend what’s lost when federal funding dries up,” says Christopher Worsham, MD, a critical care physician and researcher at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coauthor of Random Acts of Medicine: The Hidden Forces That Sway Doctors, Impact Patients, and Shape Our Health. “There are the obvious setbacks — ongoing projects shut down, discoveries delayed by years. But there are also the invisible losses. Labs that never form. Scientists who never get trained. A career’s worth of discovery, gone before it began.”

The eight breakthroughs highlighted below were selected with guidance from Worsham; David Jones, MD, PhD, a physician and professor of the culture of medicine at Harvard University, Boston; and Anupam Jena, MD, PhD, a physician and health economist at Harvard Medical School. But they’re just a sample of how federal research support shaped the landscape of modern medicine.

1. The Framingham Heart Study

A landmark, long-term investigation into cardiovascular disease and its risk factors.

With funding from what is now the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, researchers began tracking the health of more than 5000 residents in Framingham, Massachusetts. The goal was to understand the root causes of heart disease, which at the time was the leading cause of death in the US but poorly understood.

The study followed participants over decades, collecting information on blood pressure, cholesterol, smoking habits, physical activity, and more. It provided the first conclusive evidence linking high blood pressure and high cholesterol to cardiovascular illness. It also helped establish the role of smoking, obesity, and lack of exercise in heart disease. This led to the widely used Framingham Risk Score, which estimates a person’s 10-year risk of developing cardiovascular disease.

Jena says this first epidemiologic effort “helped steer the development of both preventive guidelines and treatments.”

Now in its 77th year, the Framingham Heart Study continues to follow the children and grandchildren of the original participants. Its scope has broadened to include genetics, dementia, cancer, and social determinants of health — making it one of the longest-running and most influential population studies in medical history.

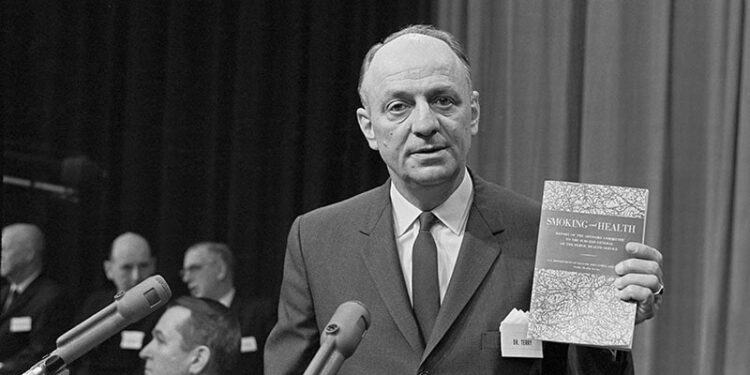

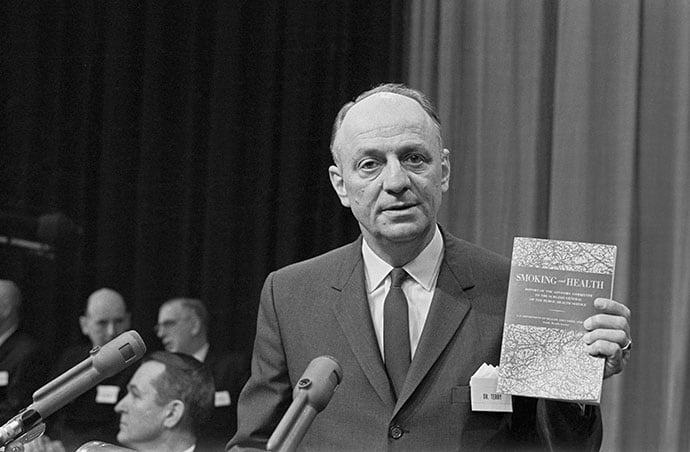

2. The Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health

The official wake-up call on tobacco’s deadly toll.

On January 11, 1964, Surgeon General Dr. Luther Terry delivered a message that would reverberate across the nation: “Cigarette smoking is a health hazard of sufficient importance to the US to warrant remedial action.”

The Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service marked the first time the US government formally linked cigarette smoking to serious disease. Previous warnings didn’t carry the weight of this 387-page document, published under the authority of the US Public Health Service and backed by decades of evidence — much of it supported, directly or indirectly, by federal research funding.

At the time, 42% of American adults smoked cigarettes daily. Tobacco advertising was ubiquitous, and tobacco companies were politically powerful. But the report flipped a switch: Within a year, Congress mandated warning labels on cigarette packages. The findings helped lay the groundwork for tobacco control policies that led to dramatic declines in smoking rates and prevented millions of premature deaths.

Jones calls it “likely the most important public health innovation of the post-World War II era.” The report established a precedent for rigorous, government-backed assessments of environmental and behavioral health risks. Subsequent Surgeon General reports would expand on the dangers of secondhand smoke, the effects of nicotine addiction, and more.

3. Oral Rehydration Therapy

A simple sugar-and-salt solution that has saved tens of millions of lives.

In the late 1960s, cholera remained a deadly global threat. The disease, which causes severe diarrhea, could kill patients within hours by rapidly draining the body of water and essential salts. At the time, intravenous fluids were the standard treatment, but access was limited, particularly in the poorer countries where cholera outbreaks were most severe.

Enter Dr. Richard Cash, a young physician who joined the NIH during the Vietnam War as an alternative to military service. The NIH sent him to what was then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), where he and colleagues helped develop and test a stunningly simple solution: a mixture of water, salt, and glucose that patients could drink themselves.

Plain water can’t reverse cholera’s rapid dehydration. Cash and his team showed that this precisely balanced oral formula could enable the body to absorb both water and electrolytes through the intestinal wall. Even patients in critical condition could recover — so long as they were conscious and able to drink.

The impact was staggering. “Oral rehydration therapy, pioneered by Richard Cash and others, has saved tens of millions of lives globally,” says Jones. Families can be trained to administer it at home. It doesn’t require refrigeration, a sterile environment, or high-tech equipment.

Field trials in the 1970s showed a 93% effectiveness rate. The Lancet in 1978 called it “potentially the most significant medical advance of the century.”

4. CRISPR Gene-Editing Technology

A revolutionary tool for editing DNA.

CRISPR emerged through decades of federally funded research into bacterial immune systems, molecular biology, and the intricate machinery of DNA repair. Today, it’s among the most promising medical technologies of the 21st century — a gene-editing technique that could treat or even cure a wide range of genetic diseases.

The foundation was laid in 2008, when researchers Erik Sontheimer and Luciano Marraffini identified CRISPR as a general purpose gene-editing mechanism. But the breakthrough came in 2012, when Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna showed that CRISPR-Cas9 could be used to precisely cut DNA in a test tube.

Doudna, a Nobel laureate in chemistry and professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of California, Berkeley, says the potential now exists to “cure genetic disease, breed disease-tolerant crops, and more.”

“CRISPR is a great example of the success of the long-standing US model for supporting science,” Doudna says. “The NSF and DOE supported the early, curiosity-driven research that led to the discovery of CRISPR gene editing, and later funding from the NIH supported the development of applications of CRISPR in human health.”

5. Vaccines for Measles, Polio, and COVID-19

Immunizations have nearly eliminated devastating infectious diseases.

Over the past century, publicly funded vaccine development has helped eradicate polio from most of the world, curb measles transmission in the Americas, and sharply reduce the global toll of COVID-19.

“Is there any doubt about the value of those vaccines?” says Jones. “Polio was a massive source of fear, with summer epidemics shutting down pools, movie theaters, and other public spaces across the US….Now polio has been nearly eradicated from Earth.”

Measles, meanwhile, was declared eliminated from the Western Hemisphere in 2016 (though recent outbreaks are raising concerns about that status).

Public investment was crucial to the development of these vaccines. The measles vaccine, developed by John Enders and his team at Harvard, was made possible through NIH-supported research into how to culture the virus — a critical step toward producing a safe and effective vaccine, licensed in 1963. It laid the groundwork for the combination MMRV (measles, mumps, rubella vaccine) developed in 1971. In 2005, the varicella (chickenpox) vaccine was added, creating the now-standard MMRV shot for children.

The polio vaccine emerged from a public fundraising campaign that started when President Franklin D. Roosevelt (a polio survivor) and Basil O’Connor founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis — later renamed the March of Dimes — which channeled donations into research and care. Their support enabled Dr. Jonas Salk to develop the first inactivated polio vaccine at the University of Pittsburgh in the early 1950s, leading to mass immunization efforts that would all but eliminate the disease from most of the world.

The COVID-19 pandemic spurred the fastest large-scale vaccine development in history. Within 12 months of the SARS-CoV-2 genome being published, researchers — backed by tens of billions in US public funding — had developed multiple highly effective vaccines. That NIH investment (estimated at just shy of $32 billion) helped accelerate development and manufacturing, allowing the US to lead a global vaccination effort. Over 13 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses have since been administered worldwide.

“The evidence is quite good that COVID vaccines saved lives and reduced suffering,” says Jones. A new study from JAMA Health Forum offered one of the most comprehensive and conservative estimates to date: COVID-19 vaccines averted 2.5 million deaths in the US between 2020 and 2024 — reinforcing the enormous public health return, even under modest assumptions.

6. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

The federal agency is quietly making healthcare safer, smarter, and more efficient.

Despite a modest staff of around 300 people and a budget of just 0.02% of total federal healthcare spending, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has a far-reaching impact on American medicine. AHRQ plays a critical role in improving the quality, safety, and effectiveness of healthcare delivery.

AHRQ was established by a law signed in 1999 by President Bill Clinton, succeeding an agency created in 1989. The need was obvious following two landmark reports from the Institute of Medicine: To Err Is Human (1999), which revealed that medical error was a leading cause of death in the US, and Crossing the Quality Chasm (2001), which called for systemic reform.

Since then, AHRQ has become the backbone of the patient safety and quality improvement movement in the US, supporting thousands of research projects and building essential infrastructure for analyzing healthcare delivery.

One example: An AHRQ-funded study evaluated the use of a standardized sterile checklist to prevent central line infections in ICU patients. As hospitals adopted these practices, “infection rates plummeted,” a study showed. “There was no new technology,” Worsham says, “just a change in practice behavior.”

AHRQ has also helped bring data science into modern health services research, giving researchers access to standardized, national healthcare data.

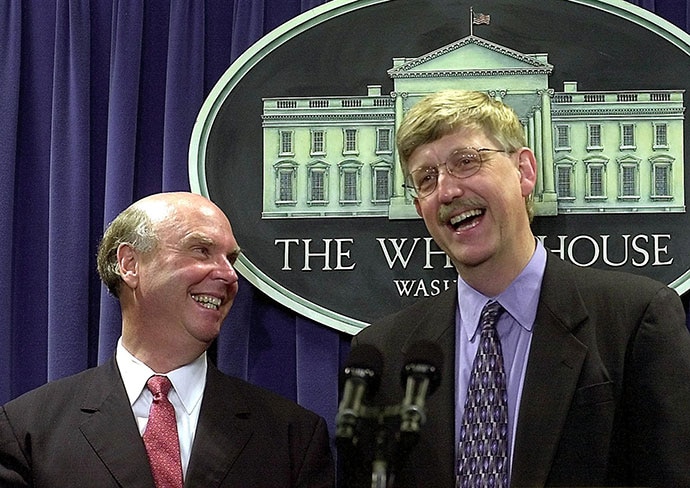

7. The Human Genome Project

A global effort that decoded the blueprint of human life — and revolutionized medicine.

On June 26, 2000, President Bill Clinton declared the completion of “the most important, most wondrous map ever produced by humankind.” He was referring to the successful first draft of the human genome: a complete survey of the genetic code that underlies all human biology.

The Human Genome Project began in 1988 as a joint initiative of the US Department of Energy and the NIH, with an initial investment of $3 billion. Over the next 15 years, it evolved into a massive international collaboration that delivered the first full sequence in 2003. The work laid the foundation for modern genomics and enabled entirely new approaches to understanding, diagnosing, and treating disease.

Dr. Francis Collins, who led the project between 1993 and 2008, told the White House gathering, “We have caught the first glimpse of our own instruction book, previously known only to God.”

Collins, the former director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, told NPR this summer that he knew then “this would become fundamental to pretty much everything we would do in the future in human biology. And I was also convinced as a physician that this was going to open the door to much better ways to diagnose, treat, and prevent a long list of diseases that we didn’t understand very well.”

The impact has been profound. The project sparked advances in personalized medicine, cancer genomics, and rare disease diagnostics. It led to the creation of tools that are now standard in medical research and enabled a generation of scientists to ask more precise, data-driven questions about human health.

8. Protease Inhibitors for HIV/AIDS

Antiretroviral drugs that turned HIV into a manageable chronic illness.

By 1994, AIDS had become the leading cause of death for Americans aged 25-44 years. Treatment options were limited, and a diagnosis often meant a sharply shortened life expectancy. That changed in 1995, when a new class of drugs — protease inhibitors — was introduced as part of a novel treatment approach known as highly active antiretroviral therapy. The results were immediate and dramatic.

Protease inhibitors work by targeting an enzyme called HIV protease, which is essential to the virus’s ability to replicate. The drugs disrupt the virus’s life cycle, reducing viral loads to undetectable levels when taken consistently. The first FDA-approved protease inhibitor, saquinavir, was quickly followed by others, including ritonavir, indinavir, and nelfinavir.

The scientific foundation for these breakthroughs was laid by researchers at the National Cancer Institute, the federal agency that played a central role in both mapping the structure of the HIV protease enzyme and designing early versions of the drugs.

Jones says protease inhibitors have “saved tens of millions of lives.” Globally, the number of new HIV infections has fallen by more than 60% since the mid-1990s.

UNAIDS officials have warned that without continued investment, particularly from major funders like the US, the world could see a dramatic resurgence in HIV-related deaths and infections.

Source link : https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/8-times-taxpayer-money-led-historic-leaps-medical-care-2025a1000kyx?src=rss

Author :

Publish date : 2025-08-07 10:07:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.