Provider: Pete Ryan

Pete Ryan

For Cherelle Gardiner, the link between her endometriosis and multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnoses, both received in her late 20s, a couple of years apart, has long been clear. “I realised that whenever I was on my period, my legs were also hurting me a lot more,” recalls the now-42-year-old, based in south-east London, of the cyclical monthly flaring-up of her two sets of symptoms.

The former is a condition in which uterine-like tissue grows outside of the uterus; the latter is an autoimmune disease affecting the brain and spinal cord. Before either of her conditions was confirmed, Gardiner pushed doctors to investigate the tingling sensations and eyesight issues that led to her MS diagnosis, and later, a scan in which endometriosis was visible. From the time of these early investigations, she remembers wondering if the two conditions were related, before her suspicion calcified into certainty.

Doctors didn’t have concrete answers for Gardiner, simply their own theories about a possible connection. A new study, however, has her feeling validated. Researchers have long observed – and women like Gardiner have experienced – that people with endometriosis are at a higher risk of developing chronic conditions. And now scientists from the University of Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Women’s and Reproductive Health seem to have uncovered why that is. Their research suggests that a shared biological basis underpins endometriosis and autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases, including MS.

“This study marks a real shift in how we understand endometriosis,” says Nilufer Rahmioglu, a postdoctoral research scientist and joint senior author of the study. “It’s the beginning of a much clearer picture – like fitting a key piece into a long-missing part of the puzzle – which could help us understand not just endometriosis, but how it fits into a broader network of immune-related diseases.”

Putting together the pieces brings us several steps closer to discovering the definitive mechanisms behind endometriosis, and also speeds our way to better treatments – and even a cure.

What we know about endometriosis

There is little certainty when it comes to endometriosis. The condition is thought to affect about 1 in 10 women, particularly those of reproductive age. The true incidence rate is likely to be higher, however: endometriosis is chronically underdiagnosed (see “Getting an endometriosis diagnosis” below), and people can spend years being told that they just have “painful periods”.

The condition derives its name from “endometrium”, the tissue that is shed each month during menstruation. “Normally, this lines the uterus like a carpet lines the floor,” explains Shree Datta, a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist. “But imagine, then, that you find carpet on the door or the ceiling.” When endometrial tissue grows in places it shouldn’t, such as on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, bladder and bowel, it can lead to a host of devastating symptoms: infertility, fatigue and – foremost – pain, in the pelvic area, bladder and bowel, and during sex.

The cause is also unclear. “We’re still going on historical theories from the late 19th and early 20th centuries,” says Thomas Bainton, a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. In 1940, American gynaecologist John Sampson posited that the condition was caused by “retrograde menstruation”, which sees menstrual blood flow backwards into the pelvic cavity instead of out of the body. This is still a popular theory; however, why and how this relatively common occurrence would then cause endometrial cells to implant in other organs is unclear. Inflammation has been another investigative focus. In June, a large Swedish study discovered that adverse life experiences from birth to age 15 – such as moving house a lot or having a parent with substance-abuse issues – could increase a woman’s likelihood of developing endometriosis, with the study’s authors suggesting that higher levels of inflammation in the body could be to blame.

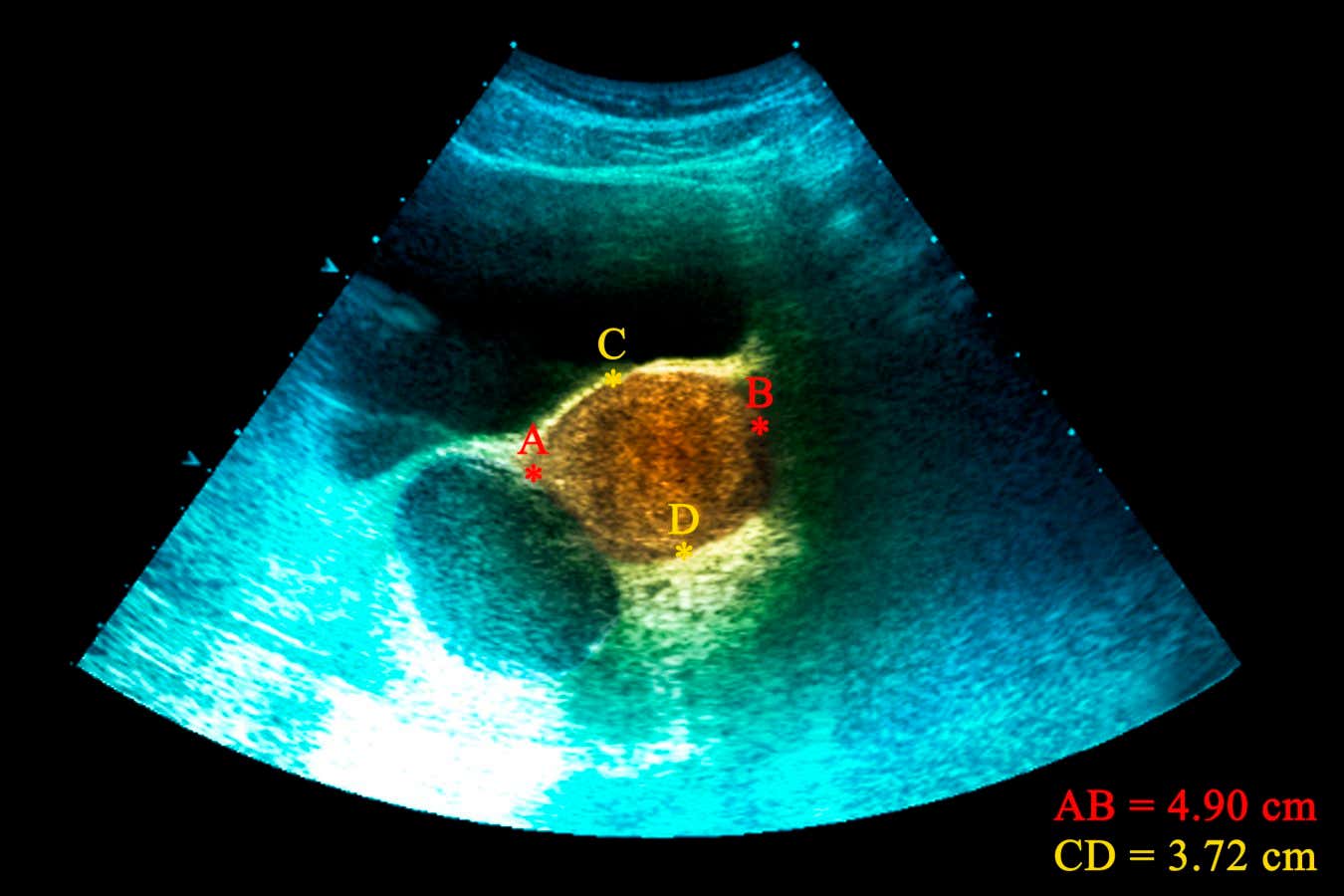

An ultrasound of an endometrioid cyst – caused by endometriosis – found in an ovary

ZEPHYR/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Other mysteries remain. Though women are between four and seven times as likely to be diagnosed if a first-degree relative also has a diagnosis, there isn’t a clear pattern that runs in families, suggesting that it could be the product of both genetic and epigenetic contributions. Oestrogen appears to be a driver of the growth of endometrial tissue outside of the uterus – symptoms intensify around times that oestrogen peaks and ease off during menopause – but the exact mechanism is unclear.

The autoimmune link

Something painfully clear to many is that endometriosis seems to frequently occur alongside other health conditions. Research has long shown a link with a host of autoimmune conditions, while a meta-analysis from earlier this year found that endometriosis is associated with a 23 per cent increased risk of cardiovascular diseases and a 13 per cent increased risk of hypertension. Other research has also uncovered a possible raised risk for ovarian and breast cancers.

“But none really went into why,” says Rahmioglu. Using data from the UK Biobank, including from more than 8000 endometriosis cases and close to 65,000 women with immune-related conditions, Rahmioglu and her colleagues examined the association between endometriosis and 31 different immune conditions, including MS, coeliac disease, psoriasis and osteoarthritis. They found that women with endometriosis had a 14 per cent higher risk of developing a single immunological disease than women without, but also that this risk compounded – they had a 21 per cent increased risk of having at least two immunological conditions, and a 30 per cent increased risk of having at least three at any point in their lifetimes.

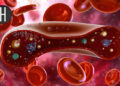

So far, so in line with previous research. But then came the breakthrough. Using vast amounts of genetic and health data, the researchers scanned the entire genetic blueprint of thousands of people to find tiny differences that might be linked to disease. They then went even further, using another method to see if one condition might actually cause another. In doing so, they found several spots in human DNA that seem to influence both endometriosis and autoimmune conditions such as MS, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

One of these shared DNA regions, for example, is involved with the expression of a gene that contributes to cell growth, immune response and tissue repair. Another regulates several genes that control how immune cells move through the body during periods of inflammation. One more shared region is known to be active in pain signalling, which Rahmioglu suggests may help explain the shared mechanisms underlying chronic pain experienced across the conditions.

“Large-scale investigations that integrate clinical and genetic data, such as this one, are uniquely positioned to unlock meaningful insights into disease mechanisms,” says Andrew Horne, a clinician and researcher at the University of Edinburgh, UK, who wasn’t involved in this research. Rather than simply observing a correlation, the study’s identification of the underlying shared genetic mechanisms establishes a solid biological foundation for why these conditions tend to co-occur, he says.

The Ziwig endometriosis analysis laboratory in Tercis-les-Bains, south-western France, is working to understand more about the condition

GAIZKA IROZ/AFP via Getty Images)

In the short term, this points to possible earlier intervention for both endometriosis and autoimmune conditions. For example, the Oxford team also uncovered a potential causal link specifically between endometriosis and rheumatoid arthritis, meaning that the presence of one could contribute to the development of the other. Knowing that there is a relationship between the conditions means that people who develop one can be more closely monitored for the development of the other, allowing them to start treatment earlier. “While this isn’t part of routine clinical practice yet, the groundwork is already being laid through research like ours,” says Rahmioglu.

In the longer term, she says, work is being done to offer even more granularity, in the hopes of potentially identifying sub-groups who may be more likely to develop specific conditions. “We have pinpointed certain genetic variants and genes that need to be further investigated,” she says.

The future of endometriosis treatment

But perhaps most significantly to the millions of people living with endometriosis, the findings offer the hope of new treatments. “The identification of this connection is not only exciting – it also opens up promising new avenues for intervention, with the potential to inform the development of therapies that could address multiple conditions simultaneously,” says Horne.

Uncovering the overlapping pathways that may drive endometriosis and autoimmune conditions can inform the development of new treatments and the repurposing of existing drugs. “The fact that we now see shared genetic architecture between these diseases opens up the possibility that similar biological processes may be involved in subgroups of women with endometriosis, and we may be able to test treatments already in use without starting from square one,” says Rahmioglu. Though clinical trials would still be needed to determine whether drugs already approved for treating autoimmune conditions would be effective for endometriosis, the path is significantly shorter and less costly than developing an entirely new drug. “It can save years,” she says.

“

The identification of this connection is not only exciting – it also opens up promising new avenues for intervention

“

That a link has become clear only now is something that amazes Gardiner. “I thought that MS and endometriosis had an established relationship already, such was the cyclical pattern of my symptoms,” she recalls. “I can remember the exact moment a potential connection dawned on me – I was looking down a hospital corridor, soon after my [endometriosis] diagnosis, and I thought, ‘Hang on a minute, are these two related?’” She took her idea to her endometriosis consultant and MS nurse, who shared the same working theory: that because her body was fighting two different things, perhaps one could be “exacerbating” the other. This was more than a decade before Rahmioglu’s team would join the dots at a cellular level. “I feel so validated that research is finally shedding light on this, but also frustrated it has taken so long,” says Gardiner, who has met many others also experiencing both conditions. “It couldn’t have been a coincidence.”

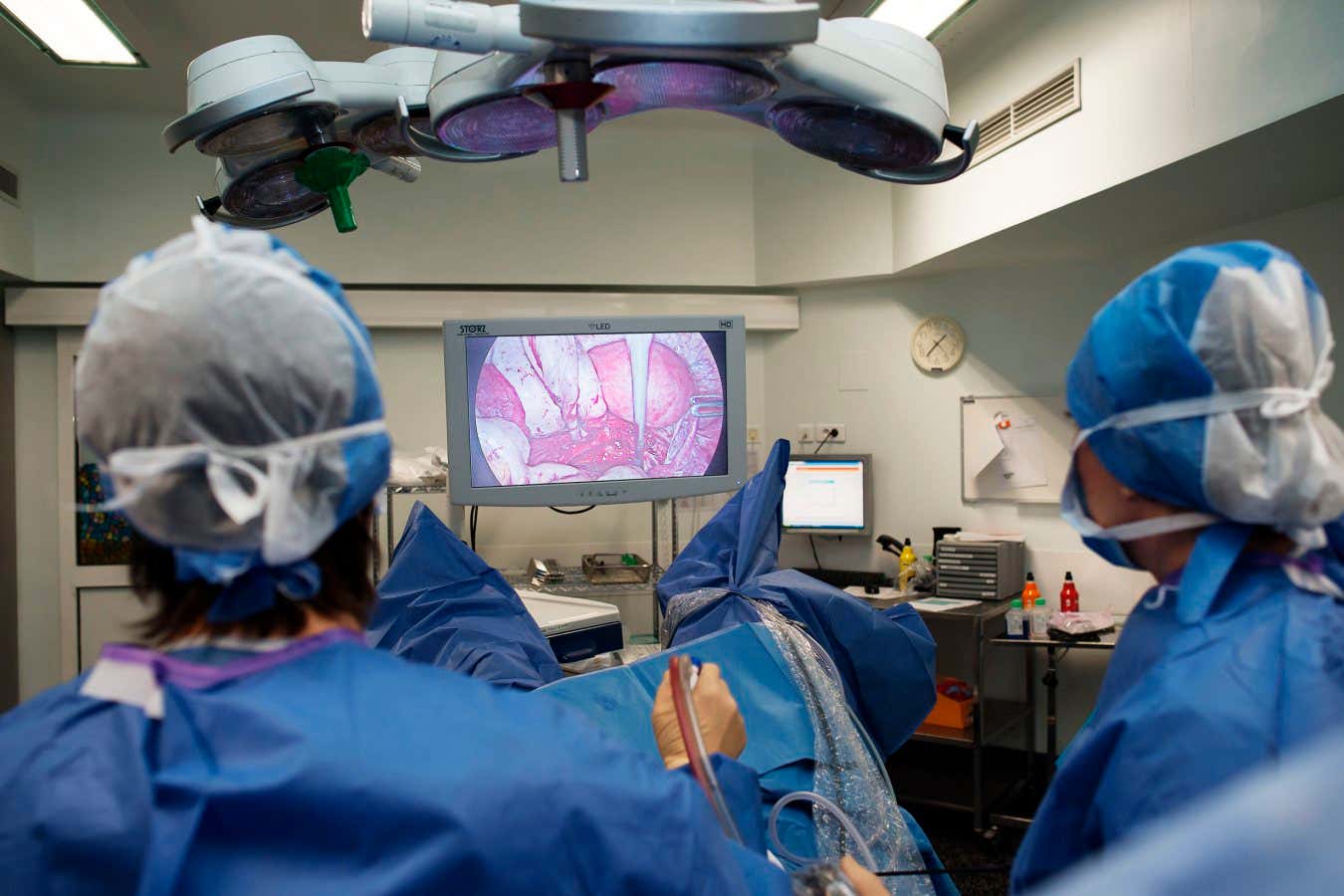

Laparoscopic surgery to remove endometriosis is one way to treat the condition, but it is invasive and can be expensive

BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

That research is revealing a new understanding of endometriosis is cause for hope, something that researchers and people living with endometriosis say is in short supply with existing treatments. “Treatment options at the moment are three-fold,” says Joel Naftalin, a consultant gynaecologist at University College London Hospitals: over-the-counter or prescription pain relief; hormonal methods, such as contraceptives, which inhibit endometriosis growth by “shutting down” the reproductive system; or removing the tissue through surgery.

These are often deployed in combination, but researchers say treatments tend to fall short. Surgery to remove or destroy endometrial tissue is no guarantee that it won’t return, while hormonal treatments come with side effects and complications, like diminished fertility and sexual function. For example, in March and May of this year, two new daily pills, Ryeqo and linzagolix, respectively, were approved by the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); they work by reducing the production of oestrogen and progesterone to ward off the growth of endometriosis cells. However, the pills come with a trade-off: the new medications tip the body into a “menopause-like” state, warns Datta. “For some patients with debilitating symptoms, these can help, but they aren’t suitable for those thinking about pregnancy, for example.”

Repurposed autoimmune treatments could offer substantive alternatives to existing therapies. Already, some scientists are exploring similar avenues. Bainton is involved in a year-long study in which participants with severe endometriosis are given monthly infusions of an immunotherapy medication designed to dampen the effects of a protein that contributes to the condition. “Treating endometriosis with immunotherapies is a new horizon,” he says, estimating that the medication could become available by the 2030s.

Evidence also suggests that targeting inflammation – an immune response implicated in the development of autoimmune conditions – could be a way to home in on endometriosis. Last year, Yale researchers were able to identify and attack the cells associated with inflammation in endometriosis. By knocking out a key protein in those cells, they were able to reduce endometriosis-like lesions in mouse models.

“

Treating endometriosis with immunotherapies is a new horizon

“

Perhaps more significant, however, is what the invigorated scientific interest in endometriosis means. The lack of treatment options for the condition has long been a problem of not only the complexity of the condition itself, but also the lack of research into women’s health historically. “But the winds are changing,” insists Rahmioglu. “Funding bodies are more aware of how common and untackled a condition it is.” For those desperate for an end to symptoms that frequently leave them unable to leave the house, like Gardiner, who is currently awaiting surgery for additional gynaecological conditions that she has now developed, such shifts can’t come soon enough.

Thankfully, scientists are upbeat about what the next decade of endometriosis care might look like. “We are seeing a shift in hopefully understanding more about this disease, including the multifactorial nature of its immune, genetic and epigenetic mechanisms,” says Mohamed Mabrouk, a consultant gynaecologist and president of the European Endometriosis League.

That, says Horne, means a more precision medicine-based approach to treating endometriosis, tailoring care for the individual – and, he says, hopefully a cure.

Like Horne, Rahmioglu stresses that the new research moves the field beyond noticing patterns in people with endometriosis and into showing that one thing is likely to be causing another on a genetic level, something she describes as a “paradigm-shifting step”.

“We’re not just observing a correlation – we’re uncovering shared genetic roots that are providing us with important biological clues and possible targets for future therapies. That gives us a real chance to accelerate progress in treating endometriosis, which has seen limited innovation for decades. The goal is to use genetic information not just to understand disease risk, but to act on it – so that care can be earlier, faster and more personalised.”

The path from suspicion to a diagnosis for endometriosis can take an astonishingly long time. Recent studies have found that even though it takes an average of 6.6 years from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis around the world, there is an enormous variation among countries, from an average of eight years in the UK to about three in Brazil. Researchers put the diagnostic delay down to a lack of popular and professional awareness about the condition, as well as the fact that symptoms can mimic other pain conditions. People living with endometriosis, however, often report feeling that their symptoms have been dismissed. Further complicating the picture, for decades, the “gold standard” for confirming the condition has been investigative laparoscopy. “But it’s an invasive test that has its own risks and complications,” says Mohamed Mabrouk, a consultant gynaecologist and president of the European Endometriosis League.

Increasingly, however, doctors have more tools at their disposal, including transvaginal ultrasounds or MRIs, to facilitate diagnoses. Andrew Horne at the University of Edinburgh, UK, is also hopeful about work on blood tests that can identify and monitor the progression of the condition. “Researchers have identified panels of protein biomarkers that are present at different levels in women with endometriosis compared [with] those without,” he explains. “These could be used to develop a non-invasive test that could potentially replace or reduce the need for surgical diagnosis.”

Australian researchers are exploring diagnosing the condition using menstrual blood, while in the US, scientists at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, have laid the groundwork for a stool test. “In menstrual blood, researchers have found certain proteins that are elevated in women with endometriosis, suggesting these could serve as non-invasive biomarkers,” explains Horne. “Stool tests focus on detecting specific metabolites and changes in gut bacteria that are linked to endometriosis, such as lower levels of beneficial bacteria and certain bacterial metabolites.” Such tests could realistically be expected to be available in the next five to 10 years, he says.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2496240-a-deeper-understanding-of-endometriosis-is-suggesting-new-treatments/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-09-22 16:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.