Thierry Nordmann was on his first night shift as a dermatologist at University Hospital Basel, Switzerland, when he got the emergency call. A patient was being brought in who’d had a severe reaction to their medication, which had destroyed the entire outer layer of their skin. Nordmann’s job was to confirm the diagnosis with a biopsy, but it was already clear: they had lost their skin’s protective barrier, leaving them wide open to infection and dehydration.

“That’s a very bad combination,” he says.

The medical staff sprang into action, isolating the patient to reduce their risk of infection and giving them antibodies in a bid to halt the immune cascade that was killing their skin cells.

But it didn’t work. The patient died – as do about a third of people with this painful condition. “The reason was because nobody really understood what was going on,” says Nordmann. “Everybody treats it differently.”

The experience left him with questions. Why do some people have this intense, lethal reaction to ordinary medicines, while others don’t? What exactly is happening in the cells of their skin?

Finding answers led Nordmann to a suite of emerging technologies that can study human tissue in astonishing detail, pinpointing diseased cells lying in the three-dimensional structure of our organs.

These technologies, known as spatial multiomics, are revealing what has gone wrong in the molecular machinery of those cells, and they led Nordmann to develop a new way to address a previously incurable, life-threatening condition. They could also lead to a raft of new treatments for other illnesses, including cancers, and usher in a new age of precision medicine.

Pathological skin

Modern medicine has spent two centuries zooming in, trying to understand why our bodies sometimes go so badly wrong. We have learned to trace diseases to organs like the heart and lungs, which are made up of tissues, which are made up of cells, which are built using a host of biological molecules like DNA, RNA and proteins.

Each level matters in truly understanding a given condition. Take the heart: cardiac arrest is when the heart stops beating, which seems simple enough, but apprehending why it happens means looking at blood pressure, narrowing of blood vessels, electrical conduction within the heart and many other other processes.

For Nordmann, the mystery was skin – and what causes it to suddenly, catastrophically, come off.

The condition Nordmann’s patient had is called toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). While it is rare, it is also brutal and can begin after taking everyday drugs like certain antibiotics or anti-epilepsy medications. For reasons no one fully understands, the immune system reacts violently. The skin becomes red, blistered and intensely painful. “Just by movement of your thumb on this redness, you can just peel away the skin,” says Nordmann. “Within 48 hours, maybe a bit longer, these patients just shed their skin.”

The effects are life-threatening. Even if people survive, they are often left with chronic complications.

“But what I’ve been seeing the most in these patients is fear,” says Nordmann. “These patients are scared of every single drug they take.” There is no obvious pattern in the treatments observed to cause TEN. And while some populations are at a substantially elevated risk, including Asian and Black people, “it can happen to almost anybody”, says Nordmann.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis can be a side effect of common drugs, like antibiotics and anti-epilepsy medications

Cristian Storto/Alamy

He suspected that the path to a viable treatment, if one existed, lay deep inside the skin. But here he found he was up against a problem that has bedevilled medical researchers for decades: even within a single organ or tissue, not all cells are alike. Two neighbouring cells can behave differently, producing a different mix of proteins and chemical signals. This means that a handful of malfunctioning cells can cause cascading damage to the entire organ.

Cancer researchers have known this for years. They talk about the “tumour microenvironment” – the idea that a tumour isn’t uniform, even under a microscope. “What’s going on at the invasive margin or leading edge of the cancer can be different than what’s going on in the central portion of the tumour,” says Frank Sinicrope, an oncology professor at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

But standard lab tools struggle to resolve these cell-to-cell differences. Analyses that sample the proteins or RNA in a tissue will generally mash together hundreds of cells in order to get a large enough sample. The result is a bit like a smoothie, which researchers can use to study thousands of proteins or other molecules.

Yet the crucial changes that researchers might still be able to spot are hidden in the mush. The signal is there, but scientists can’t say where it is happening.

There is another way to study diseased cells: look at them one by one. That became possible in the 2010s, when researchers learned to isolate single cells and sequence their entire genome. “We could identify that there were cell populations that we hadn’t understood before,” says J. Michelle Kahlenberg, a professor of rheumatic diseases at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

But there was a catch. Such methods strip the cells from their context. Once removed from their tissue, it was impossible to say where each one had come from or how it might have affected its neighbours, and thus how abnormal behaviour spreads.

Now, though, a new generation of tools is bringing that context back.

Cell by cell

Known collectively as spatial multiomics, these techniques build up a three-dimensional map of a tissue or organ. This helps researchers identify diseased or abnormal cells and profile them on a molecular level.

“We’re on the precipice of really understanding biology in a way that will revolutionise our ability to safely treat all sorts of life-threatening illnesses,” says Kahlenberg.

The term multiomics refers to the practice of studying multiple biological systems at once: genes (via genomics), RNA (via transcriptomics), proteins (via proteomics) and more. Each offers a different lens on how cells function.

Spatial multiomics goes one step further and adds high-resolution imaging to molecular analysis, allowing scientists to build detailed maps of living systems – not just what molecules are present, but where they are and how they interact across space.

Andreas Mund, a researcher at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, who helped develop the method Nordmann would later use to unpick TEN, calls it deep visual proteomics. Mund’s team described its technique in 2022, and it unfolds in four stages.

It starts with a biopsy: a sliver of tissue is fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin, then sliced into micrometre-thin sections. These are stained to highlight particular molecules.

Then things get more precise. Mund’s team uses high-resolution microscopes and AI image analysis to create detailed digital maps of the tissues, showing each cell’s boundaries and flagging those that appear abnormal.

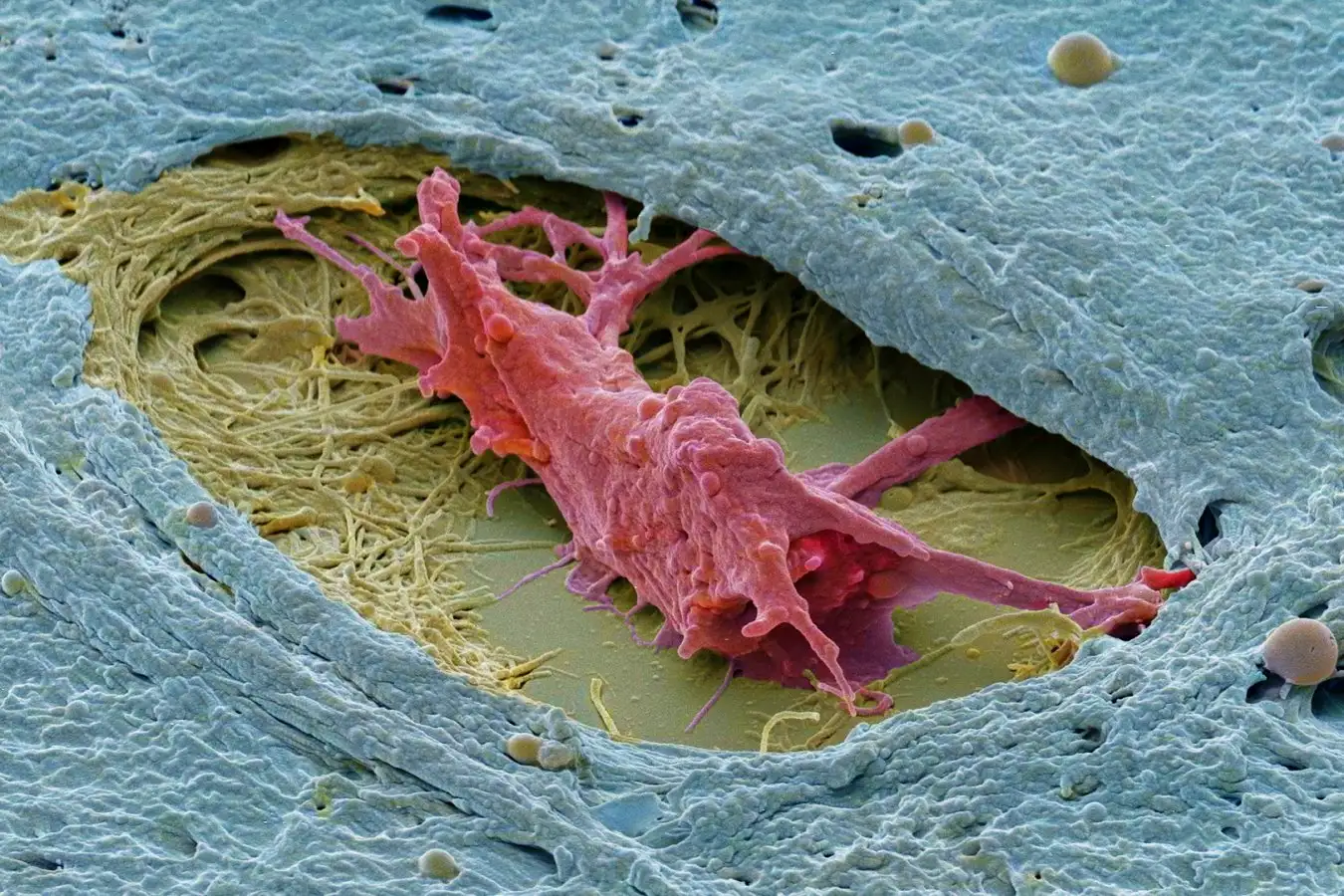

Scientists are using spatial multiomics to better understand, and hopefully treat, ovarian tumours like the one shown here

Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library

A laser dissection microscope then cuts out labelled cells one by one, tracking their position in the original tissue. Each cell is broken apart, its constituent proteins shattered and analysed by mass spectrometry, a method that weighs molecules with incredible precision. “We use the latest and greatest on the market,” says Mund. Their mass spectrometers are so sensitive that they can detect differences equivalent to the weight of a jumbo jet versus a jumbo jet with a fly sitting on it.

The outcome is a powerful molecular map: a profile of every cell and the proteins it contains. Crucially, it allows researchers to compare healthy and abnormal cells and detect patterns of dysfunction that were previously invisible.

In a paper released in July, Mund and his colleagues looked at a kind of pancreatic cancer in which tumours form from distinctive lesions within the pancreas, but not all of these lesions go on to be tumours. “Why are these so different? What are the molecular differences?” asks Mund.

To find out, they analysed over 8000 proteins across cells from five people with this cancer and 10 cancer-free organ donors. Even cells that looked normal under the microscope showed early signs of tumour development in people with cancer: inflammation, metabolic rewiring and other stress markers. “There’s a lot of things already happening under the surface,” says Mund.

He and his team argue their work could lead to biomarkers for earlier detection, a major step for one of the deadliest cancers.

And deep visual proteomics is just one part of this new set of technologies, each aimed at unravelling the spatial story of disease in place, cell by cell.

Spatial multiomics

Another promising way to track what is happening inside a cell is by looking at its RNA.

RNA plays a key role in gene expression. Genes store instructions in DNA, but to act on them, cells first transcribe that information onto RNA. The resulting RNA then guides protein production, the main outcome of gene expression. By examining which RNA molecules are present in a cell, a profile known as its transcriptome, scientists can get a snapshot of the cell’s condition, including what it is trying to do or cope with at any given time.

Spatial transcriptomics involves mapping the cells in a tissue and then studying their individual transcriptomes. “Spatial transcriptomics, I think, takes us to the next level,” says Kahlenberg.

In July, researchers led by Ernst Lengyel at the University of Chicago used spatial transcriptomics to develop a potential treatment for ovarian cancer. They focused on a group of cells called cancer-associated fibroblasts, which help tumours grow. These cells were already known to respond to an enzyme called NNMT. Using spatial transcriptomics, they discovered that this response caused fibroblasts to release chemicals that dampened the immune system, shielding the cancer. That insight led the team to create an NNMT inhibitor that, in mice, enabled the immune system to go to work and reduce the growth of tumours.

Surgeons perform laparoscopic surgery on a 58-year-old woman with ovarian cancer

Dr P. Marazzi/Science Photo Library

Transcriptomics and proteomics are complementary, says Sinicrope, because they give different kinds of information about the cell. “RNA gives us more in terms of the pathways and the signatures.”

Now, some researchers are trying to combine the two to get an even more multilayered picture of what is happening in diseased tissue. In August, Lengyel and his colleagues used spatial transcriptomics and proteomics to map out changes in ovarian tumours, leading them to identify 16 potential drug targets – two of which have since showed promise in mice.

Meanwhile, halfway across the world at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Nordmann was using spatial proteomics to crack the TEN mystery.

New treatments

Nordmann arrived in Martinsried, Germany, from his position in Switzerland, armed with Mund’s new approach of studying diseases and a drawer full of skin samples from people with TEN. Having followed Mund’s team’s work on ovarian cancer, he and his colleagues sought to understand the underlying mechanisms that cause skin to detach in TEN.

The deep visual proteomics revealed a striking pattern. In the immune cells of the TEN patients, a molecular system called the interferon pathway was massively overactive. “I have really never seen such a clear picture in my life,” says Nordmann.

Normally, interferons are produced by cells in response to viral infection. They prompt other cells to activate their antiviral defences. But in Nordmann’s TEN patients, there was no virus: the interferon response was a mistake and was causing the immune system to destroy the outer layer of their skin.

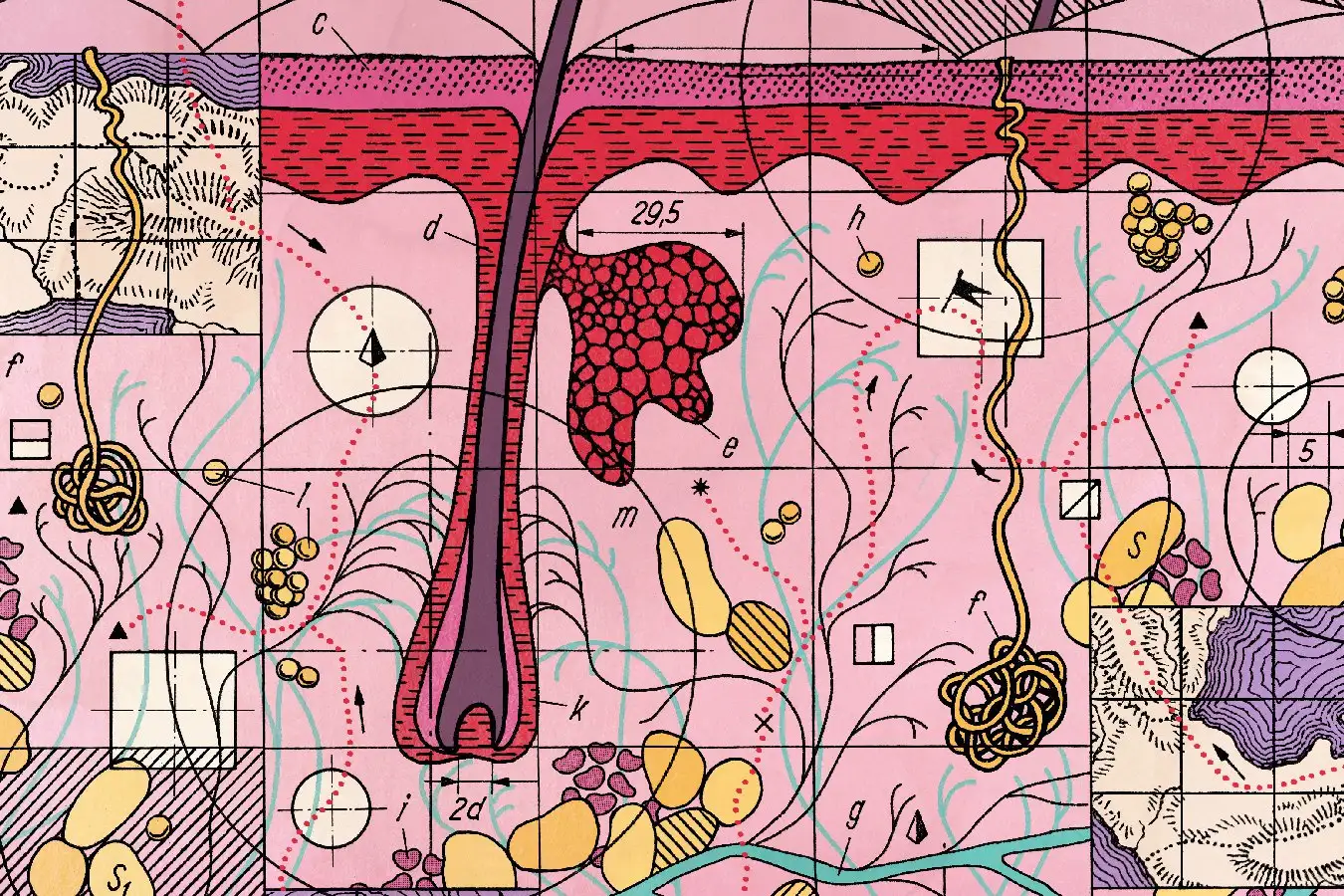

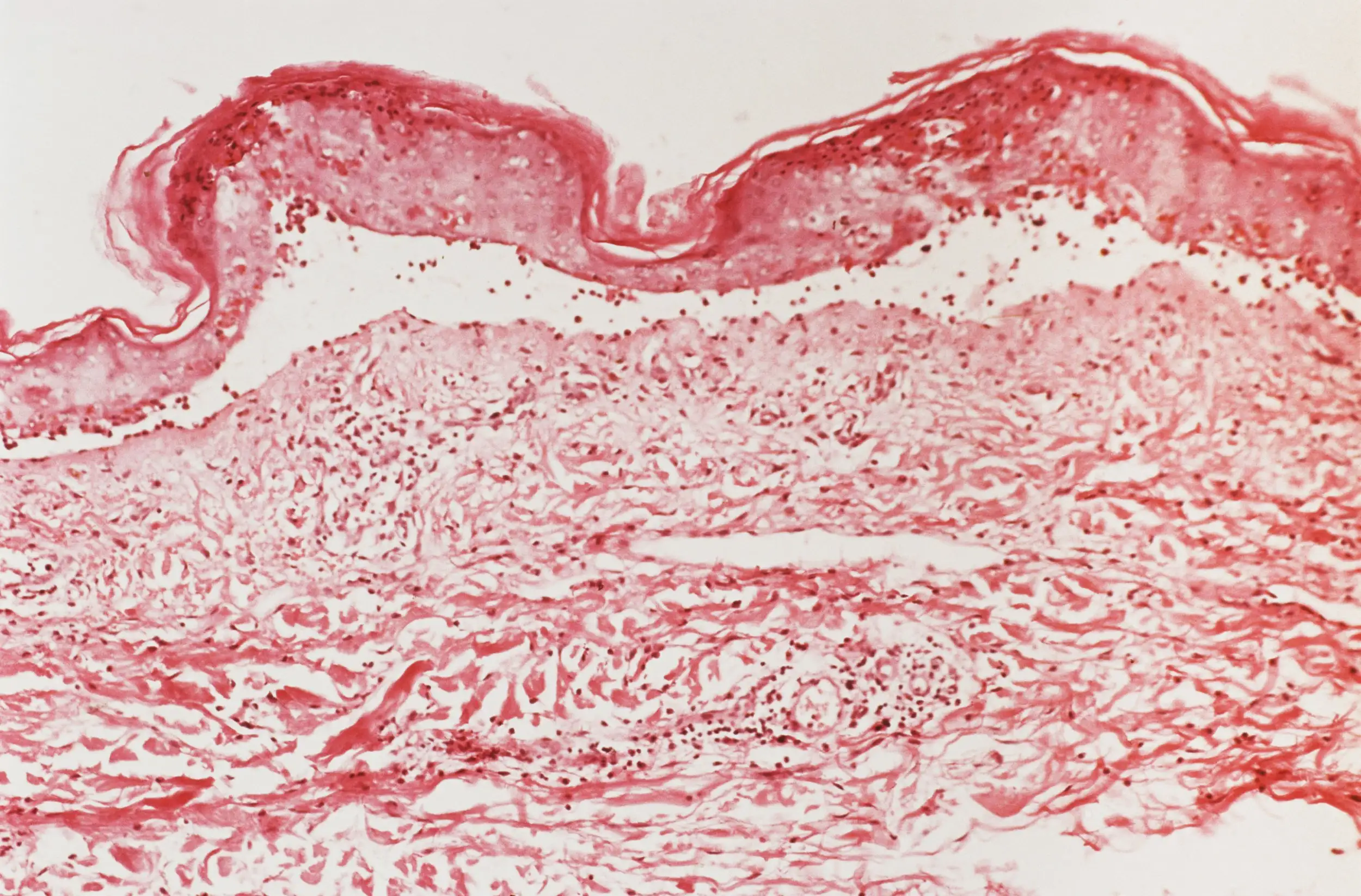

A micrograph showing the top layer of skin starting to detach in someone with toxic epidermal necrolysis

Biophoto Associates/Science Photo Library

The team discovered that a signalling pathway called JAK/STAT was driving the cells to produce interferons.

Excitingly, drugs already exist that block this signalling pathway, as it is implicated in other inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and atopic dermatitis, so they could work for TEN too. “The cool thing is, there are already inhibitors out there,” says Nordmann.

With the help of Chao Ji at Fujian Medical University in Fuzhou, China, Nordmann launched the first human trial in 2023. They treated seven TEN patients, all of whom were still alive with no side effects 30 days later, the duration of the study. One man who had lost 35 per cent of his outer skin grew almost all of it back within 16 days; the treatment halted cell death in all patients and promoted a regrowth of skin.

Though it wasn’t a controlled study, because the team didn’t want to give some TEN patients a placebo, Nordmann is now trying to get a pharmaceutical company to set up a full clinical trial.

For the first time, TEN had been effectively treated. Nordmann and his colleagues’ work is a dramatic illustration of the potential of spatial multiomics. It’s a huge leap forward from where doctors were just a few years ago, when they were forced to treat TEN patients essentially as severe burn victims: giving them fluids, anti-inflammatories and something for the pain.

“My personal opinion is, in two to three years’ time, this will be the standard treatment for this disease,” says Nordmann.

It will take a while before spatial multiomics technologies are used widely in research and in clinics. Running a few hundred samples through spatial multiomics can cost millions of dollars. But some hospitals are already placing big bets on this new approach.

The Mayo Clinic has established a Spatial Multiomics Core to perform such analyses. The researchers there hope to better understand atherosclerotic plaques, which are a major element of heart disease, by figuring out what their many component cells are doing.

Similarly, diabetes can cause complications in the gut by affecting the cells of the gut lining, so identifying the cells most prone to such damage would be a key step in preventing it.

And for his part, Sinicrope, who leads the Spatial Multiomics Core, is optimistic that spatial multiomics will help with cancer, especially solid tumours.

Meanwhile, Mund and his colleagues founded a company called OmicVision in 2023 off the back of their deep visual proteomics technique, with the aim of reducing how laborious and complex it is to carry out. With improved AI image analysis, Mund hopes to drive the cost of deep visual proteomics down and make the technology more widely available. “Our mission is really to move the needle,” he says.

Five years since he started working with spatial multiomics, Nordmann remains thrilled by its potential. “You get an entire new picture, an entire new understanding of the molecular information within a tissue,” he says. “It gives us new ideas of how to diagnose them, understand them, treat them.”

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2504372-a-revolutionary-way-to-map-our-bodies-is-helping-cure-deadly-diseases/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-11-26 16:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.