Imagine you’re standing in front of a closed door. Behind it is a teenager’s bedroom, and your task is to rate how messy it is on a scale of 1 to 10. But here’s the twist: you can’t open the door – and you don’t even know what kind of stuff might be inside.

If that sounds a tall order, try being a physicist. For the better part of 50 years, they have been wrestling with the knotty problem of black hole entropy, a question about how messy or disordered these behemoths are on the inside. Everyone knows you can’t see inside a black hole, but it’s worse than that. No one is even quite sure what the concept of disorder means when you are talking about an epic, inaccessible hole in the fabric of space-time.

For decades, theorists have tried to answer this using the tools of quantum mechanics, only for their calculations to explode into meaningless infinities. But now, a breakthrough with an incredibly complex branch of mathematics has changed the game and finally allowed us to calculate the messiness of a black hole. The result was deeply unexpected, but it might just be telling us something new and profound about the way space-time works.

“We ultimately hope that this lesson about black holes isn’t just about black holes,” says theoretical physicist Gautam Satishchandran at Princeton University.

What is entropy?

The first ideas about entropy were born in the steam age. Physicists like Ludwig Boltzmann grappled with why engines, no matter how cleverly they were designed, seemed to always lose energy in the form of waste heat. In the 1870s, he came up with an understanding of entropy that focuses on a hidden underworld.

“[Boltzmann’s] notion of entropy counts all the possible configurations of particles in a system that lead to the big macroscopic measurements we can make about it,” says theoretical physicist Netta Engelhardt at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Picture a room full of gas molecules, she explains, ricocheting off one another in chaotic motion. There are numerous ways to arrange these molecules, most of which involve them being spread out fairly evenly. Only a few would gather them all into one corner. Boltzmann realised that entropy was a measure of how many microscopic configurations, or “microstates”, produced the same large-scale appearance. Swap two molecules and nothing changes – temperature, pressure, volume all stay the same. But behind that sameness lie vast numbers of potential arrangements.

This was a watershed moment. Boltzmann linked entropy to the invisible ballet of tiny atoms – a bold move, considering that scientists at the time still believed such particles to be a convenient fiction. Yet Boltzmann’s equations predicted the behaviour of gases with such uncanny accuracy that they helped cement the atomic view of matter.

Ludwig Boltzmann wanted to understand why entropy always rises over time in systems, like the steam engine

Bettmann/Getty Images

But then in the early 20th century, along came quantum mechanics, and with it a whole new perspective on entropy. In the 1930s, polymath John von Neumann extended entropy into the quantum world. There, particles don’t have fixed properties like position or momentum. Instead, one can give only probabilities of finding certain outcomes when a particle is measured. Von Neumann showed that entropy could quantify the uncertainty inherent in quantum mechanics.

He also managed to capture the way parts of a quantum system can become entangled. In an entangled system, two regions – or even two particles – can be so deeply connected that learning something about one instantly tells you something about the other, no matter how far apart they are. Von Neumann’s entropy also considers how our knowledge of one part of a system may depend entirely on what we can observe in another.

But there’s a crucial divide here between the two visions of entropy. Boltzmann’s version came as a built-in feature of the world, a tally of the possible microscopic rearrangements you can make to the building blocks of a system. Von Neumann’s, by contrast, captures our imperfect knowledge of the quantum world. Boltzmann’s entropy is a statement about what is; von Neumann’s is a statement about what we know.

The black hole paradox

There aren’t many people who can say they got one over on Stephen Hawking. Yet that is exactly what Jacob Bekenstein, then a graduate student at Princeton University, did in the early 1970s. He argued that black holes had to have an entropy – or else you could violate the second law of thermodynamics, which says the universe’s total entropy must always increase. Throw something into a black hole, and its entropy would vanish. That didn’t add up.

Hawking was unimpressed. Entropy, as every self-respecting physicist knew, was a measure of disorder, a kind of physical bookkeeping for what’s going on inside a system. And black holes, by definition, had no insides.

But in trying to prove Bekenstein wrong, Hawking instead discovered Hawking radiation, a quantum glow around black holes generated by particle-antiparticle pairs near the event horizon. This radiation implied black holes have a temperature – and where there’s temperature, there must be entropy.

Hawking later joked about putting the black hole entropy equation on his tombstone. “Hawking and Bekenstein essentially set off the field of black hole thermodynamics,” says Jonah Kudler-Flam, a theoretical physicist at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton.

This discovery just raised more questions. Boltzmann tied entropy to something physical: the hidden microstates of a system. So if black holes have entropy, did that also imply they had a hidden interior? For decades, physicists have been divided on what, if anything, exists inside a black hole – but the hope was that they could recreate Boltzmann’s magic and use entropy to figure out the underlying microscopic structure.

Just what would this structure be? An arrangement of particles that had fallen beyond the event horizon? Or something stranger, like entangled bits of quantum information? Some physicists even suspect these hidden ingredients might not be particles at all, but more abstract building blocks – the elemental units from which space-time itself emerges. “We’re trying to understand what are the atoms of space-time,” says Jonathan Sorce, a theoretical physicist at MIT.

Crack that mystery and physicists might not just understand black holes – they might glimpse the long-sought unification of general relativity and quantum theory. These two great frameworks of modern physics collide most violently inside black holes. By understanding what these gravitational monsters are made of, we might finally bring both theories under the same roof.

For decades, researchers struggled to make headway. That was partly for obvious reasons. “We can observe the exterior of the black hole,” says Sorce. “But we are totally ignorant to what’s inside it, because it is literally a black hole.”

But it was partly also because of mathematical limitations. In the wake of the Hawking-Bekenstein breakthroughs, theorists had turned to the quantum view. Maybe von Neumann’s entropy, which uses a kind of mathematical tool set called operator algebra, could expose something about the invisible structure of space-time inside a black hole. Yet every time they tried, the quantum approach kept ending in failure, yielding the hardest kind of results to reconcile with tangible reality: a slew of infinities.

The reason, says Satishchandran, lies in the nature of von Neumann entropy itself. It is measuring what can be known – what a quantum observer can, in principle, detect.

Imagine drawing a boundary around a chunk of space – the region between two stars, say. What can you know about it? In quantum theory, there are no built-in limits on what you can measure. Zoom in as far as you like; space can always be sliced finer, revealing more detail.

“If you ask me what I can measure about some volume of space, the answer is infinity,” says Satishchandran. “I can know an infinite number of things about it to an arbitrary precision.”

Ridding black holes of infinity

The problem runs deep. The mathematics of quantum theory, operator algebras included, wasn’t built to handle gravity. It treats space-time as a fixed stage. But general relativity says space-time bends and flexes in response to matter and energy.

That discrepancy hardly matters in most quantum systems, where gravity is so weak it can be ignored. Yet near a black hole, where quantum fields roil in violently curved space-time, that blind spot breaks everything, and it shatters hopes of uniting the strange world of quantum theory with general relativity more generally.

But in 2023, a team of theorists, including string theory heavyweight Ed Witten at the IAS, decided to flip the script. What if they stopped treating space-time as static and instead allowed it to take part in the quantum churn? Using the mathematical machinery of operator algebras, they wove gravity into the calculations from the ground up.

The maths is fiendishly complex, but the idea is simple: quantum fields tug on space-time, and space-time tugs back. This feedback loop proved to be the missing ingredient – stabilising the calculations and stopping them from spiralling into infinities. “Normally, when you give me two badly behaved things and add them together, I would expect something worse,” says theorist Daine Danielson at Harvard University. “The fact that they’re badly behaved in equal ways is a glimmer of some deeper structure that’s better behaved.”

This theoretical breakthrough laid crucial groundwork for Satishchandran and his colleagues to pick up the thread. Earlier this year, they used Witten’s tweaked mathematics to calculate the von Neumann entropy of a black hole. By taming the infinities, they could measure how the black hole’s external surface is entangled with bits inside – a bridge between inside and out.

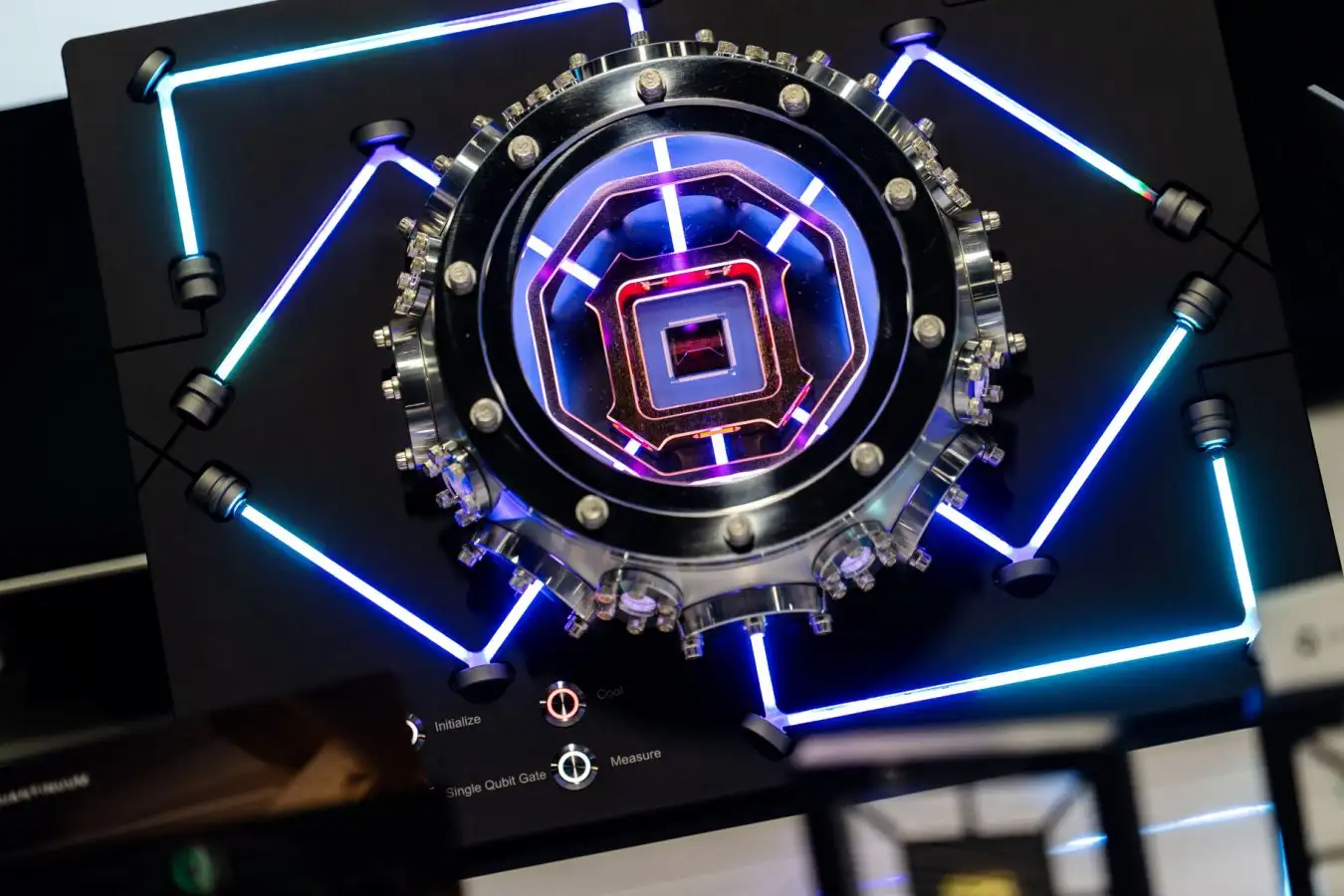

The development of quantum computers, like this Quantinuum model, rely on our understanding of Von Neumann entropy

Kent Nishimura/Bloomberg via Getty Images

What they found was striking. The entropy of a black hole, the one first calculated by Hawking and Bekenstein using thermodynamic arguments, turned out to be exactly equal to the von Neumann entropy. It’s a powerful convergence. On one side, von Neumann entropy measures what we don’t know in a quantum system. On the other, the Bekenstein-Hawking entropy measures a physical property of space-time. And yet here they are, the same.

If that sounds wild to you, you’re not alone. “I think it’s very provocative,” says Danielson. It echoes the original shock of quantum mechanics: that reality isn’t just what is, but what can be measured. And now, black holes seem to follow the same rule. The entropy we observe outside – once considered a thermodynamic oddity – turns out to be a faithful stand-in for everything going on inside.

It’s a big revelation, akin to finding out that standing outside the door of that teenager’s chaotic room is enough to deduce exactly what’s inside. It goes beyond the interior that Bekenstein and Hawking hinted at decades ago. We no longer just suspect there is something behind the horizon, but that we may also never need to peer inside a black hole to decode its full story.

The precise ingredients of a black hole, whether quantum fields or tiny vibrating strings, remain unknown. But physicists believe that careful measurements near the event horizon could eventually be enough to reconstruct its quantum structure.

The line between what’s real and what’s observable is growing thinner. “Right now, we see many pieces of a bigger jigsaw puzzle,” says Hong Liu, a physicist at MIT. “Whether we have all the pieces, we don’t know.”

The entropy of the cosmos

Black holes aren’t the only cosmic boundaries drawing attention. If entropy reveals something essential about space-time at a black hole’s edge, perhaps it can do the same at the universe’s outer limit.

That edge, called the cosmological horizon, marks the furthest we can observe. Because the universe’s expansion has outpaced light since the big bang, there are regions from which no signal – no light, no information – will ever reach us. Eerily, these horizons behave much like a black hole’s event horizon: what lies beyond is unknowable.

Hawking extended his entropy calculations to this boundary too. The result, the Hawking-Gibbs equation, mirrors his black hole formula, encoding the entropy of an expanding universe in the curvature of space-time.

The observable universe is the region of space that humans can theoretically observe

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Satishchandran and his colleagues applied the same operator algebra tools to these cosmic horizons, asking whether entropy could also describe how space-time behaves here – and offer more clues to quantum gravity.

Imagine all the information that can possibly reach you from the universe’s distant corners, says Satishchandran. That stream of light is shaped by the geometry of the space it travels through, the structure of space-time, but it is also defining the limits of what we can possibly measure and know. Once again, we see entropy split along familiar lines: one shaped by what is, the other by what we can observe. In working through this tension, physicists hope to tease out what space-time is truly made of.

So far, the results have been uncanny. Satishchandran and his collaborators have once again found that the Hawking-Gibbs entropy – this expression of space-time’s geometry – is equal to the von Neumann entropy, the measure of quantum uncertainty.

“It’s extremely suggestive,” he says. And it leads to a profound implication: that gravity may possess some of quantum mechanics’ stranger behaviours.

Other research with the same approach has come to similar conclusions. Early this year, a team at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan published a paper arguing that gravity itself is observer-dependent.

Because different observers access different parts of the universe, the researchers argue, this shapes what they can measure. On a quantum level, that changes the information they can extract – and with it, the entropy they assign to a region of space-time.

And because gravity is encoded in the geometry of space-time – and geometry, in turn, encodes entropy – the implication is startling: gravity may not be a fixed, universal force at all. It could emerge differently for different observers.

But the path to a full theory of quantum gravity, says Satishchandran, is still far from complete. What’s emerging now is just the latest leg of a journey that began, improbably, in the 19th-century science of steam engines.

“Operator algebras might not be the final answer,” he says. “But they’ve opened a door that wasn’t there before. Now we’re trying to see how far we can push it.”

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2505176-black-hole-entropy-hints-at-a-surprising-truth-about-our-universe/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-12-02 16:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.