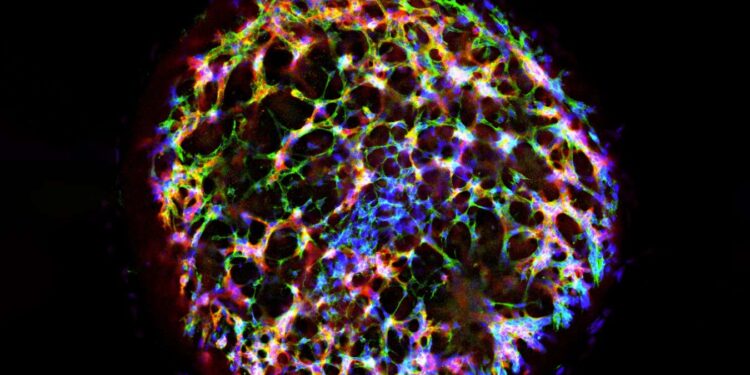

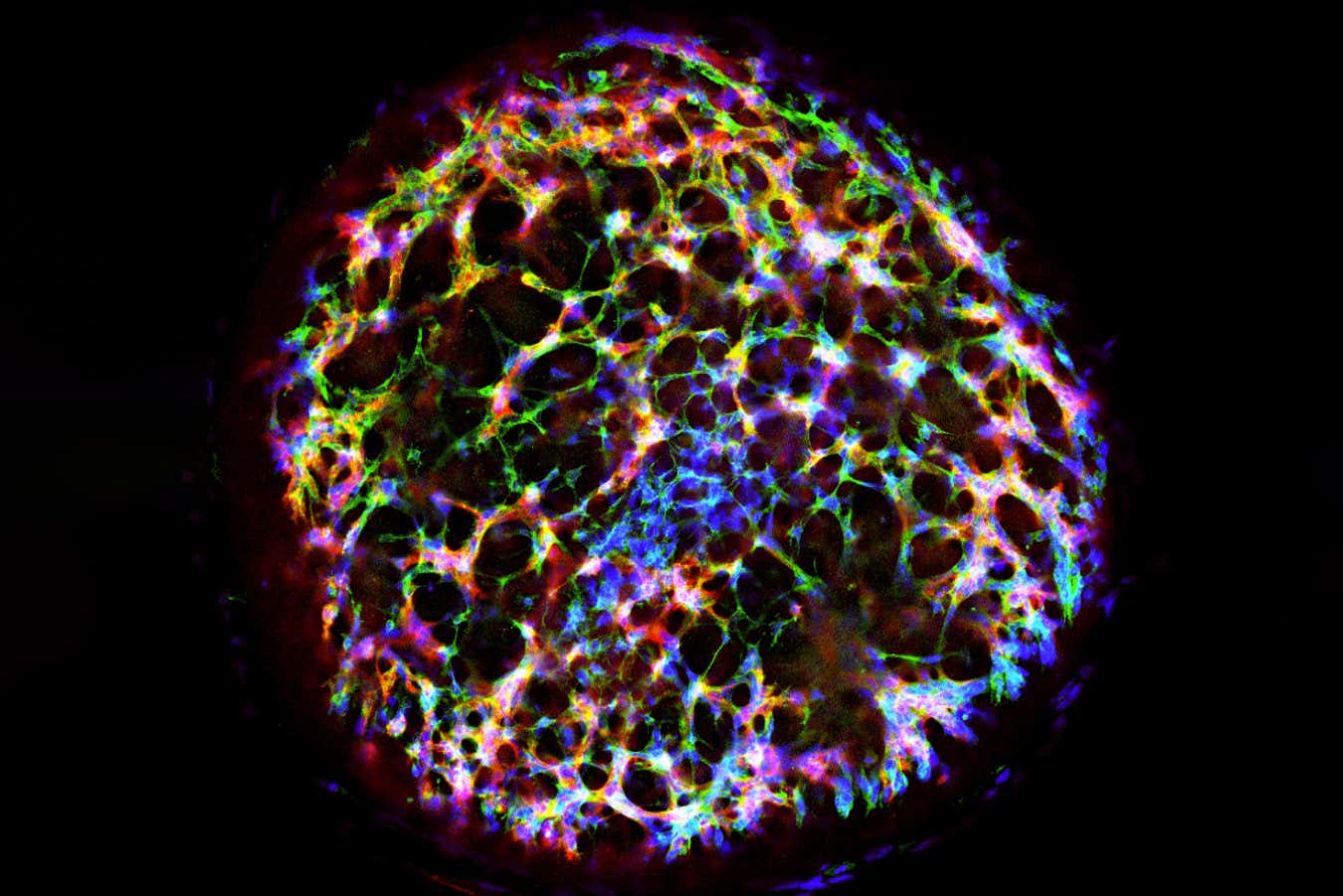

A human vascular organoid generated from stem cells

Melero-Martin Lab, Boston Children’s Hospital

Tiny balls of lab-grown blood vessels helped restore blood flow to injured tissue in mice, minimising necrosis. This approach could one day be used to reduce some of the damage caused by accidents or blood clots.

Researchers have previously made clumps of lab-grown blood vessels, known as organoids, by immersing human stem cells in a cocktail of chemicals. But this approach takes a few weeks and often produces vessels that poorly mimic those in the body, says Juan Melero-Martin at Harvard University.

In an alternative approach, Melero-Martin and his colleagues genetically engineered human stem cells that were made by reprogramming skin cells. They gave the stem cells a genetic sequence that causes them to develop into blood vessels in the presence of the antibiotic doxycycline. “We managed to get blood vessel organoids in just five days,” says Melero-Martin. The vessels also had protein and gene activity levels that were highly similar to those found in the human body, he says.

To test whether their organoids could treat injured tissue, the researchers surgically cut off the blood supply to one leg of several mice, so it was less than 10 per cent of normal levels. One hour later, they implanted 1000 organoids at each of the injury sites.

When imaging the mice two weeks later, the team found that the implanted blood vessels had fused with those already in the animals, restoring blood supply to 50 per cent of normal levels – a substantial amount, says Oscar Abilez at Stanford University in California. “For example, in a heart attack situation, if you can restore that much blood flow to tissue, in a reasonable time, that would be significant for reducing tissue damage.”

After treatment, about 75 per cent of the animals had minimal levels of dead tissue, says Melero-Martin. Among those that were injured and not given the implanted blood vessels, most of the leg tissue died in around 90 per cent of individuals.

In another experiment, the researchers used the organoids to treat mice with type 1 diabetes, where damage to the pancreas causes blood sugar levels to get too high. They found that implanting the organoids into the mice alongside transplants of pancreatic tissue substantially improved their blood sugar control, compared with transplanting pancreatic tissue alone.

But further studies in larger animals such as pigs are needed before the approach can be tested in people, says Abilez. Melero-Martin says the team hopes to do this, adding that human studies could realistically take place within five years.

Besides treating tissue injury, the findings could help the development of lab-grown mini-organs that better mimic what is happening in the body or even mini-tumours that scientists can study and test treatments on in the lab.

“Until recently, those organoids can only grow to a certain size, because they don’t have blood vessels – so, after a certain size, a few millimetres, they start to die,” says Abilez. “This study offers a way to add blood vessels to those organoids so that they better represent the physiology of a human, and are more useful for developing treatments.”

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2484221-blood-vessel-organoids-quickly-minimise-damage-to-injured-tissue/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-06-13 16:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.