A growing body of research shows that complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) can help treat certain gastrointestinal disorders. With up to 44% of people with diagnosed gastrointestinal (GI) disorders using CAM, chances are most gastroenterologists — whether they know it or not — are seeing patients who take products or engage in practices that fall under its umbrella.

Many gastroenterologists are unfamiliar with CAM because it isn’t widely taught in medical school. “Some doctors even discourage the use of CAM because they’ve never heard of a given intervention,” said Gerard Mullin, MD, associate professor of medicine and director of the Johns Hopkins GI Clinical Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland.

Unfortunately, many patients aren’t telling their doctors about their CAM use because they’re afraid of being judged, Mullin said. Patients also may not disclose their CAM use because they don’t realize it’s important to share with their physician or their doctor simply hasn’t asked them about it.

But CAM’s popularity makes it important for gastroenterologists to be educated about what their patients may be using, the risks and benefits of various CAM products and practices, and the evidence base that might or might not support their use.

Gastroenterologists also may want to incorporate CAM into their practices to offer what’s known as integrative gastroenterology. Many arguments support this approach, Mullin, editor of the book Integrative Gastroenterology, told Medscape Medical News.

Digestive disease rates are very high and are increasing, he noted. “The escalating prevalence of obesity, anxiety, depression, stress, consumption of ultraprocessed foods, and food-borne illnesses contribute to a digestive disease epidemic,” Mullin told Medscape Medical News. “Adopting an integrative model can contribute to more effective prevention and treatment of these conditions.”

CAM comprises an array of different modalities and approaches, from oral products to mind-body practices and alternative styles of medicine.

This article cannot provide an exhaustive analysis of all CAM interventions for GI conditions, but it reviews several evidence-based approaches for common disorders.

Why CAM?

David Hass, MD, associate clinical professor with the Division of Digestive Diseases at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, became interested in integrative medicine because he treated many patients who came to him after consultations with other physicians for troublesome symptoms of disorders of the gut-brain interaction, also known as functional gastrointestinal disorders.

“These patients can be difficult to treat,” he said. “Many have undergone multiple studies and scans and tried multiple medications. I wanted to be helpful and explore what else might be out there for them that may not be traditional or mainstream but is evidence-based.”

CAM is appealing to patients because these approaches often provide a sense of control of their bodies and health and because they offer an alternative when conventional approaches fail to alleviate symptoms or provide a cure, said Hass, a partner at the Physicians Alliance of Connecticut in Hamden and coauthor of a review article on CAM for functional GI disorders.

Interventions once considered alternative have attracted more research attention and become more accepted in the conventional medical community, Nitin Ahuja, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine (gastroenterology) at Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told Medscape Medical News.

For example, L-glutamine therapy has been found to alleviate symptoms in postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with diarrhea and intestinal hyperpermeability. Until relatively recently, the concept of intestinal permeability or “leaky gut” had been “discussed mostly in alternative health spaces.” But an increasing body of evidence now supports the legitimacy of the diagnosis in certain GI conditions.

Similarly, mind-body medicine was once categorized as alternative medicine. But interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based approaches are gaining traction in conventional circles and amassing evidence of its efficacy.

“Additionally, while a substantial gap remains between anecdotal and empirical understandings of some of the approaches previous considered ‘alternative,’ they also raise thought-provoking mechanistic hypotheses and invitations for further research,” said Ahuja, who is also director of the Program in Neurogastroenterology and Motility, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Pennsylvania, and author of a review article critically appraising popular remedies for esophageal symptoms.

Dietary Supplements

Several herbal products have been shown as effective for GI conditions. For example, ginger has been found to be generally safe and useful in treating nausea and vomiting. However, it can inhibit platelet aggregation and potentially be mutagenic, so it should be used cautiously in patients already taking antiplatelet therapy and in pregnant women. Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) has been shown to be helpful with nausea during pregnancy.

For functional dyspepsia, peppermint and caraway have been researched extensively. In a number of studies, both agents have yielded statistically significant improvements in bloating and epigastric pain compared to placebo.

Several herbal products can protect the stomach and esophagus in the setting of gastritis and when a patient is transitioning off proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Zinc carnosine and glutamine can protect the gastrointestinal lining, repair damaged cells, stabilize gut mucosa, and decrease inflammation. Glutamine may play a role in supporting the gut microbiome and gut mucosal wall integrity and in modulating inflammatory responses.

Other nutrients that help decrease inflammation and restore the mucosal lining include apple pectin, marshmallow root, slippery elm bark, licorice root, and okra, Steve Irsfeld, RPh, owner and pharmacist in charge at Irsfeld Pharmacy, Dickinson, North Dakota, told Medscape Medical News. Irsfeld recommends curcumin, which has anti-inflammatory properties in the gut, and bovine colostrum.

He told Medscape Medical News that he believes histamine 2 blockers and PPIs are overprescribed for heartburn and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

“They’re designed to suppress stomach acid, but they’re being prescribed without verifying that hyperacidity is actually present,” he said. “We wouldn’t prescribe antihypertensives or statin drugs, for example, without checking the patient’s blood pressure or cholesterol, but we administer PPIs without ascertaining stomach acid levels merely on the assumption that if the patient has symptoms or visible inflammation, the acid levels must be elevated.”

Prolonged use of PPIs can have adverse effects, including infections, impaired nutrient absorption, dementia, kidney disease, hypergastrinemia, and a rebound effect upon discontinuation.

Studies have found that the herbal preparation STW-5 (Iberogast) can improve symptoms of epigastric pain and GERD, Hass noted. The product contains bitter candytuft, chamomile, peppermint, caraway, licorice root, lemon balm leaves, celandine, angelica root, and milk thistle.

To promote colon health, Irsfeld recommends probiotics. “We’re now able to recommend highly targeted probiotic strains,” he said. For example, Saccharomyces boulardii has been shown to be helpful in counterbalancing the effects of antibiotics on the gut microbiota during antibiotic therapy. After antibiotic discontinuation, the patient can transition to a different probiotic.

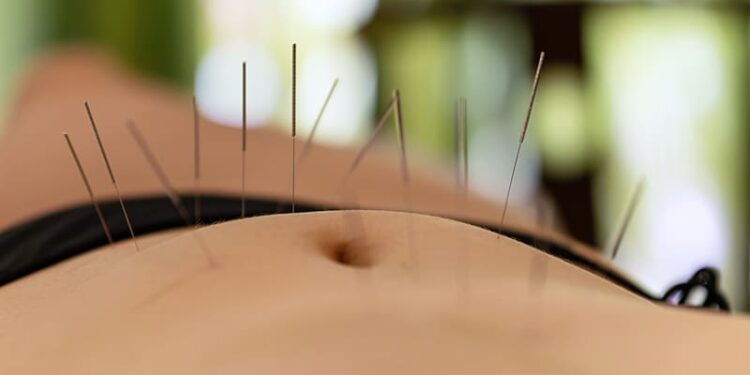

Acupuncture and Traditional Chinese Medicine

Acupuncture, the application of small needles or pressure to specific points in the body, is rooted in traditional Chinese medicine, in which health is regarded as stemming from the alignment of qi, or “vital energy.” Its practitioners aim to remove blockages or reduce excesses in qi, which flows through specific channels in the body, known as meridians.

“In acupuncture, there are meridians that govern the GI system,” Shi-Hong Loh, MD, of Dao Sheng Acupuncture, Hoboken and Hackensack, New Jersey, told Medscape Medical News. “Meridians are typically not tied to Western concepts of anatomy or neurology. The points we use are often related to the parasympathetic nervous system, with nerve distribution from areas in the thoracic and lumbar spine. That type of nerve innervation is from the spinal area and controls abdominal and intestinal function.”

Acupuncture is highly personalized, Loh said. “Everything is specific to the condition and the individual, and the interpretation of each practitioner.”

Manual and electroacupuncture have shown utility for patients with GI conditions, including functional GI disorders, constipation, GERD, inflammatory bowel disease, ileus, acute pancreatitis, and gastroparesis. A recent systematic review of 10 randomized controlled functional MRI trials comparing acupuncture to sham acupuncture, moxibustion, placement on a waiting list, or medication found that acupuncture improved GI symptoms and psychological status in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders and regulated functional connectivity and activity in brain regions associated with visceral sensation, pain regulation, and emotion.

Loh said that in addition to acupuncture, he often recommends Chinese herbs and encourages patients to identify whether their eating patterns affect their conditions.

“When I see a patient with GI symptoms, such as IBS, I know the symptoms are often related to diet, so I don’t depend on acupuncture alone. I look at the whole picture,” he said.

Loh advises patients with upper GI symptoms to “pay attention to their eating habits, daily behavior, and activities. Do they eat too much or too fast? Do they lie down soon after eating? Do they eat a lot of greasy foods? Are they taking in enough fiber?”

Acupuncture can play an important role for patients who don’t respond to conventional treatments, Loh said. “It’s reasonable for the gastroenterologist or internist to refer these patients to an experienced, knowledgeable, licensed acupuncturist,” he said.

The Mind-Body Connection

Stress is an established driver of many GI conditions. Loh described a patient with ulcerative colitis and an extremely high-stress job whose symptoms abated whenever he went on vacation. “I’ve noticed the same pattern in other patients, too,” he said.

Loh often targets acupuncture points that “calm the spirit and ease anxiety, as well as those directly addressing the intestinal symptoms.”

In addition, he often recommends psychotherapy — especially cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which has been shown to be effective for a number of GI conditions, such as IBS. A review of nine studies encompassing more than 600 patients with gastroduodenal disorders of the gut-brain interaction found that CBT effectively improved GI symptoms and psychological outcomes.

“There have been an impressive number of studies demonstrating that CBT is effective in improving symptoms of IBS when compared to usual medical care, antidepressants, placebo, antispasmodic agents, or support therapies,” Loh said.

One meta-analysis found a number needed to treat of 3 for treatment with CBT, which is “tremendously beneficial,” Hass noted. The placebo effect may play a role, he said, “but if I can help people get better with a placebo, I have no problem with that.”

Other evidence-based mind-body approaches include gut-directed hypnotherapy, meditation, mindfulness-based therapies, guided imagery, and yoga. A systematic review of six randomized controlled trials found evidence that in patients with IBS, yoga can decrease bowel symptoms, disease severity, and anxiety, as well as improve physical functioning and quality of life.

Like CBT, hypnotherapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction “aim to reduce overactivity to stressors and to improve maladaptive coping behaviors,” said Hass, who has been trained in hypnotherapy. “Particularly for anxiety-provoked symptoms due to catastrophizing, CBT would be the modality of choice.”

Hypnotherapy and mindfulness meditation have been found effective in several GI cancers, as well as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, Hass noted. Some research has shown that mind-body approaches can decrease tumor necrosis factor alpha — a cytokine involved in inflammatory bowel disease — and other inflammatory markers.

Gastroenterologists may wish to consider incorporating these evidence-based therapies into their treatment regimens for GI disorders, especially functional bowel diseases, Hass said. Using these interventions in conjunction with standard medical therapies “may alleviate symptoms more quickly than when medical therapies alone are used,” he added.

Ahuja, Hass, Loh, and Mullin reported no relevant financial relationships. Irsfeld reported being an unpaid member of the scientific board for NutriDyn, which manufactures Dynamic GI Integrity.

Batya Swift Yasgur, MA, LSW, is a freelance writer with a counseling practice in Teaneck, New Jersey. She is a regular contributor to numerous medical publications, including Medscape and WebMD, and is the author of several consumer-oriented health books, as well as Behind the Burqa: Our Lives in Afghanistan and How We Escaped to Freedom (the memoir of two brave Afghan sisters who told her their story).

Source link : https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/can-mind-body-therapies-improve-gi-outcomes-2025a1000ep6?src=rss

Author :

Publish date : 2025-05-30 14:50:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.