The Carina Nebula viewed by the Hubble Space Telescope

NASA/ESA/M. Livio, The Hubble Heritage Team & Hubble 20th Anniversary Team (STScI)

Start off in any direction and fly through the universe. Out of our solar system, beyond the edge of the Milky Way, through the forest of galaxies that make up our Local Group into the wilderness of the distant cosmos, past black holes and galaxies and near-infinite worlds… or are they infinite?

Could you keep travelling forever or would you eventually reach an edge? Or perhaps end up right back where you began? This is the biggest problem in cosmology, especially if you take the word “biggest” literally: what, exactly, is the size and shape of our universe? We’ve got a few hints, but they don’t point in any one particular direction, so it remains largely a mystery.

When I talk about the universe with friends or colleagues, I often find myself reminding them that space is huge, perhaps even unending. It’s a hard thing to get your head around, but cosmologists and great thinkers have been puzzling away at it for centuries. The best way to figure out its size is to start by sorting out what shape it is. And there are plenty of ideas for what form our universe might take.

The simplest shape for the universe would be essentially a flat sheet. Of course, it’s far more complicated than that, but it’s a useful metaphor (which you could say about most things in physics). I’m going to hand-wave past some of the technical details, but suffice it to say that if the universe is flat, all the geometry you learned in school works: draw a triangle and its angles will add up to 180 degrees and all its lines will be straight. But if the cosmos is curved, things start to get funky. Your triangle wouldn’t be a triangle as you know it, but the effects would be so small you wouldn’t notice. The universe could be shaped like a saddle or even like a sphere, and either way geometry becomes non-Euclidean and therefore a bit strange.

The size and shape of the universe are governed by two quantities: gravity and dark energy. The gravity of everything in the universe pulls it in, and dark energy pushes it to expand. If these two are perfectly matched, the universe is flat. If dark energy is winning, it’s Pringle-shaped. Either of these forms would allow the universe to be finite or infinite – there are models that work for each.

If gravity is winning, the universe is spherical and therefore finite – which is the simplest solution. However, as far as we can tell from various large-scale observations of the cosmos, it seems like the universe is probably flat. Then again, recent observations have shown that dark energy may be weakening over time, which really underlines how little we actually know for sure about the universe writ large. Dark matter is similarly mysterious, even as we build increasingly precise maps of it throughout the cosmos, and it is a crucial component in the gravity of the universe. So “probably flat” should still be taken with a grain of salt.

At this point, I should tell you that I’m not an entirely impartial narrator here. I, along with many physicists, do not like infinities. Sure, they’re fun to think about, but plug one into the physical world and what does it even mean? Maybe it’s just the limits of my human brain, but I have a hard time accepting that anything can be meaningfully infinite. Everything must have some limit, even if that limit is extremely big. Infinity strikes me as a bit of a cop-out. There’s no way to measure it. If our equations aren’t working right, we’ll just assume it goes on forever? Give me a break.

I’m not alone in that view, and given the general distaste for infinities, there are a lot of theories of what a finite universe might look like. Even if it’s flat, there are plenty of options for how different parts of space-time might be connected to one another – like I said, the sheet/sphere/saddle distinction is a simplification. For one, there’s the question of whether a finite universe has to have an edge. If the universe is finite and flat like a sheet of paper, it must have one – but then we must ask, what’s beyond the edge? Maybe other universes, maybe nothing at all. It could be anything. But what happens right at the edge? Does existence just… stop? That’s a bit unnerving and hard to imagine, and it’s also hard to work into the equations that describe our universe.

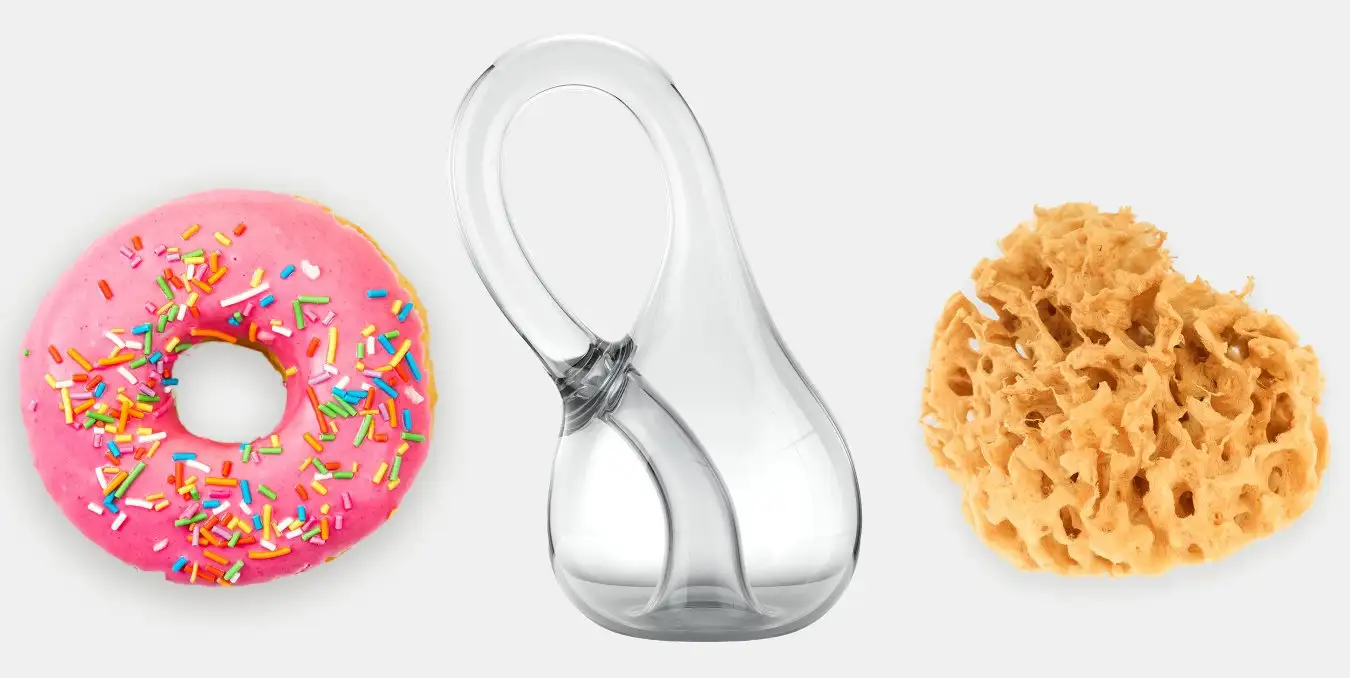

Is one of these the shape of the universe?

Nataliia Pyzhova, MAXSHOT.PL, Sashkin/Shutterstock

If space-time is curved, the options open up a little bit. A sphere doesn’t have an edge, so if you travelled too far in one direction, you’d just end up back where you started. Or it could be shaped like a doughnut or a Klein bottle or a weird wormhole-pocked sponge, or any number of other possibilities – some physicists have suggested it could be shaped like a peanut, a cone or an apple, the last of which is made possible only by adding more dimensions than we currently exist in. Like I said, it’s complicated.

All those shapes that I just mentioned are finite. Add infinities into the mix and it all gets even wilder – one might even say unwieldy. You could travel forever and all you’d find is endless space, an infinite variety of galaxies and stellar systems and worlds. There’d be no worrying about edges or what’s “outside” the universe because everything would be inside it.

In some sense, the prospect is exciting. You could find anything out there. There’d definitely be other life forms – just by sheer probability – although that pretty much still holds for a universe that isn’t infinite but just really, really big. Personally, though, I can’t help but think that an infinite amount of universe is just too much. I love imagining what might be out there, but if the answer is “everything possible because the universe goes on forever and ever”, there seems to be no point in imagining.

Those are personal feelings, though, and like everything in physics, in the end it’ll come down to observations and maths. That’s part of what I love about physics, its concreteness – and infinity just isn’t concrete enough. If I choose a direction and fly off through the universe, eventually I want to reach something, whether it’s an edge or just home again.

Mysteries of the universe: Cheshire, England

Spend a weekend with some of the brightest minds in science, as you explore the mysteries of the universe in an exciting programme that includes an excursion to see the iconic Lovell Telescope.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2515390-can-we-ever-know-the-shape-of-the-universe/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2026-02-16 08:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.