At the time of posting, 61 human cases have been identified in the United States.One case in Louisiana — the first severe case reported in the United States — has led to hospitalization. The patient was most likely exposed to the D1.1 genotype through “sick or dead birds in backyard flocks.”

Following recent detection of cases in dairy cattle in Southern California, the state’s Governor, Gavin Newsom, declared a state of emergency. The effort is intended to increase efforts to monitor and mitigate the disease. Livestock managers are encouraged to contact state or federal food and agriculture authorities should any unusual number of animals become sick.

No human-to-human transmission has been detected, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) public health risk level remains low.

Medscape Medical News spoke with Demetre Daskalakis, MD, MPH, who is the director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC, about what healthcare providers need to know regarding recommendations for testing and treatment of H5N1 in the United States.

Text has been edited for length.

This commentary was created as part of a collaboration between the CDC and Medscape Medical News. Please read additional Q&A features and commentaries at: CDC Expert Commentary.

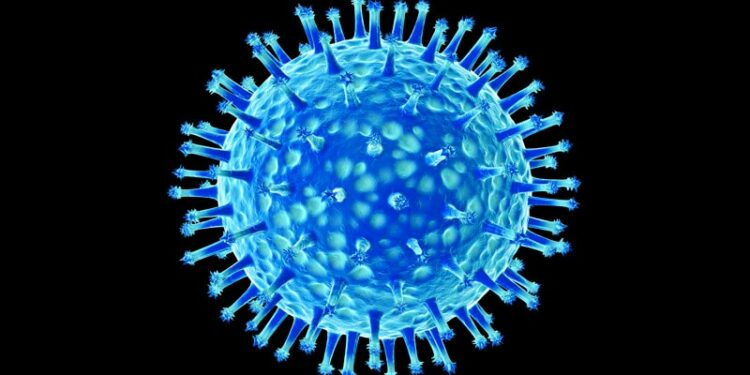

What is the level of concern regarding H5N1?

Daskalakis: We’ve been concerned about H5N1 for 20 years. When you think about respiratory viruses that have pandemic potential, you mostly think about influenza viruses.

Influenza viruses are twitchy, they can infect different animals, there’s risk of a change in the virus that can lead to more efficient transmission from animal to human and from human to human. Because we know that influenza has that potential for changing, whether it’s shift or drift or both, there’s always a concern that influenza could trigger a bigger outbreak or a pandemic.

This is why we’re so closely monitoring this situation and why ongoing efforts to improve controls in animals are so important to what happens in humans. The new testing order from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) is important to both understand the prevalence of these infections in cows and provide the data needed to better control this infection in cows. The USDA is using a model for this program that they used decades ago to address brucella in cows.

If we start to see anything different, if we identify more severe disease that’s happening in humans consistently, if we’re seeing any evidence of enhanced transmission from animal to human, or if we’re seeing limited human-to-human transmission, that would change our risk assessment and public health strategy.

Epidemiology is not the only consideration in assessing risk. Every time we get a positive H5 test at the CDC, we sequence the virus to see if there are any changes that would make us more concerned about enhanced transmissibility, impact on treatment effectiveness, or on expected efficacy of vaccine products identified in our preparedness efforts.

We have a multilayered influenza surveillance system that allows us to monitor influenza trends and any specific signals related to H5. When a herd or flock is identified, we work with our state and local health departments that institute monitoring, testing, and antiviral treatment or prophylaxis.

Our national influenza surveillance system is also a key part of how we monitor seasonal as well as more emergent influenza viruses. Since February 2024, we assessed over 65,000 people using this surveillance system that uses a testing protocol able to detect H5N1. As of December 6, this system has detected two cases of H5N1 in people with no history of known animal exposures. The more virus there is around in animals and the environment, the more possibility there is that a human could be exposed and potentially become infected. Along with this critical system, we also use our other surveillance systems, whether it’s emergency room visits, test positivity, or wastewater, to see if there’s any sort of influenza-related trend that would indicate possible H5N1 activity among humans.

Can you give us an update on the current status of H5N1 in the United States?

Daskalakis: The CDC continues to assess the risk to the general population of avian influenza as low, but we continue to have concern about individuals and populations who have potential exposure to animal or animal products, like those working on farms, given that is the predominance of cases that we’ve detected in the United States so far.

And that reveals the two levels of situation update that I can give. The first is where we are with animals: As of December 6, there were 720 dairy herds that were affected by H5N1 in the United States in 15 states. That could change, especially given recent updates from the USDA and a recent order about increasing testing.

We continue to also track H5N1 in other animals, including poultry. In all, 49 states have had poultry outbreaks, and we are tracking, with our colleagues at the USDA, evidence of highly pathogenic avian influenza in wild birds and other mammals, which is being seen in multiple parts of the country.

Second, in terms of where we are with human cases, we are currently at 58 human cases as of December 6. A total of 35 of those are related to an exposure to dairy cattle, 21 are related to an exposure to poultry, and we have two who do not have an identified source.

What do we know about the most recent case in California, which would be the second case with an unidentified source?

Daskalakis: The case in California is a child who presented with mild respiratory symptoms and was tested for respiratory viruses including influenza. This test was positive for influenza A and was then sent over to an academic affiliate laboratory where the sample was subtyped, revealing an H5 infection.

The California Public Health Laboratory conducted testing and subsequent specimens have been sent over to the CDC for additional workup that confirmed an H5N1 infection.

The child recovered from their illness, and contract tracing occurred that focused on the household and other areas the child visited. Importantly, no one demonstrated any positive tests for H5 in the household, although other respiratory pathogens were identified in some symptomatic individuals.

We want to highlight the importance of our influenza surveillance system that is able to help us detect situations where there’s not a known exposure, but the vast majority cases have been detected in individuals with those known animal exposures.

At this time, we are not detecting human-to-human transmission, and if we look at H5N1 cases across the globe, about 8% of cases do not have known exposures to an infected animal.

The bottom line is that all H5N1 cases are important to help us monitor and understand this virus. The epidemiologic and laboratory investigations are really important to see if we can identify a source but also make sure that there’s no evidence of human-to-human transmission or further evolution of the virus.

During the next 2-3 months, how should general practitioners approach the diagnosis and treatment of conjunctivitis or upper respiratory infection (URI) in agricultural communities? How about in other communities where there have been no H5 cases?

Daskalakis:

Currently, if you’re a clinician and you’re seeing someone with conjunctivitis, it is good to ask environmental questions, behavioral questions, occupational exposure questions, or recreational exposure questions that may suggest the need for additional testing. Things like, have you been around any dead or sick birds or animals? Do you work on a dairy farm? Do you work on a poultry farm? Are you exposed to raw milk, either occupationally or through ingestion?

In someone with conjunctivitis and/or other symptoms who has a potential animal or animal product exposure, it’s good to call your state health department to help guide the workup. Get in contact with them while you still have the patient in front of you to make sure you obtain the right specimens, which may include a conjunctival swab and other respiratory samples. It’s important to note that many of the influenza tests available on the market are not validated for a conjunctival specimen, so you want to make sure that you’re testing the right specimen with the right test.

There are commercial labs that offer H5 testing of respiratory specimens, and more of them are coming, making testing someone a bit easier. You should still contact local public health if you think you may have someone with H5N1 infection, even if you are sending the lab to a commercial provider.

And while you’re waiting for the result, for a patient with potentially high-risk exposure and suggestive symptoms, you should start treatment with oseltamivir rather than wait for the test result. Public health will also advise you on isolation recommendations for your patient and will initiate additional steps in the investigation.

Why are we not recommending that all people with conjunctivitis and URI are tested for H5?

Daskalakis: At this time, most cases of H5N1 are related to a known exposure, so the index of suspicion that conjunctivitis may be caused by H5N1 is extremely low in people without exposure history. This may change, but for now, conjunctivitis should lead a clinician to get more history to help guide testing plans.

But, if there’s a reason to get an influenza test, don’t just stop there. What we’ve seen is that even in situations where people have exposure to animals with H5 infection, we’re finding COVID, enterovirus, rhinovirus, and adenovirus. If you have the opportunity to test for more pathogens while you’re also doing appropriate testing for your concern, it is good to do.

Why is it especially important now that healthcare providers get vaccinated against seasonal influenza and recommend their eligible patients get vaccinated against influenza (and COVID-19, respiratory syncytial virus, and pneumococcus) and what are we doing for H5 vaccine readiness?

Daskalakis: It is important now, but it is always important. First, we want to make sure that healthcare providers are able to stay healthy and continue doing the work that they need to make sure that the rest of the country is healthy. We know that that seasonal influenza vaccine is important in reducing symptoms and potentially reducing the possibility of transmission. Additionally, routine influenza vaccination is recommended for all people who are aged 6 months or older who don’t have contraindications, that includes clinicians!

The real and present danger that we have today is seasonal flu, which is starting to tick up slowly across the country. When you think about influenza season, the influenza vaccine is able to prevent millions of illnesses, hundreds of thousands to millions of outpatient medical visits, up to 87,000 hospitalizations in a year and potentially up to 10,000 deaths.

When we look at influenza vaccine effectiveness, we say that it’s somewhere in the mid-40% range. That still is great in terms of preventing a lot of disease burden and impact on the healthcare system. Even when the vaccine doesn’t prevent infection, it can reduce severity of disease. Taking it from “Wild to Mild.”

Additionally, at the CDC we have launched a seasonal vaccine campaign focusing on farm workers in states with H5-positive herds. The seasonal vaccine does not protect against H5N1, but there are several reasons this campaign is important. First, seasonal influenza is dangerous, so protecting people keeps them healthy and working. Secondly, preventing influenza-like illness in a farm worker using the seasonal vaccine means fewer farm workers with flu-like symptoms and fewer unnecessary workups for H5N1. It helps differentiate a clinical H5 signal from the seasonal influenza noise.

Why is it important that patients start antivirals within hours of presenting to care (ie, why should clinicians not watch and wait, like they increasingly do when prescribing antibiotics) and self-isolate?

Daskalakis: In general, antivirals against respiratory viruses work better when started as early as possible in the course of infection. That’s true for influenza and it’s true for COVID. When you look at our guidance at the CDC, testing can help guide treatment decisions, but empiric therapy is also supported to accelerate initiation of treatment. This strategy is especially true in an individual who has had exposures to poultry or to dairy cows or dead birds. We want to make sure that we start antivirals to limit replication of the virus and reduce the possibility of more severe disease. Don’t wait for the test!

What should clinicians do to report cases and trigger an outbreak investigation, if they suspect that they are dealing with an influenza A(H5) case or some other novel influenza virus?

Daskalakis: The clinic or office is a busy place, but when you suspect H5N1, take a moment and call your local or state health department. They will guide you on specimen collection, tell you where to send it, and then also will remind you of what the guidance needs to be to support the patient — treatment and isolation. They will also then get the information that they need from the clinician to initiate a public health response.

Daskalakis had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Source link : https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/surveillance-and-ongoing-concern-h5n1-us-q-cdcs-demetre-2024a1000old?src=rss

Author :

Publish date : 2024-12-19 14:14:29

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.