Cryotherapy is emerging as a promising, low-risk approach to combat chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, a common and potentially devastating toxicity of chemotherapy.

A growing body of research suggests that cryotherapy, or cold therapy, significantly reduces the incidence of this chemotherapy-induced nerve damage, especially among patients receiving taxane-based chemotherapy.

Despite the encouraging evidence, cryotherapy is not a standard intervention for this common side effect of chemotherapy. Knowledge gaps and barriers to adoption remain.

“I’ve seen it work in patients,” said Alexandre Chan, PharmD, MPH, an oncology pharmacist and cancer supportive care researcher at the University of California, Irvine. “But there are a lot of practical questions that we still need to tackle before we say, ‘okay this should be standard of care.'”

Inside Extreme Cold Therapy

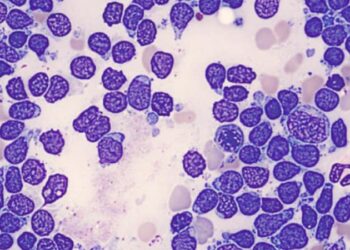

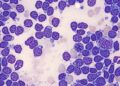

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy — nerve damage from chemotherapy — typically affects the fingertips and toes, which can lead to numbness and tingling. Patients can also experience pain, heightened sensitivity to temperature and touch, and in rare cases, muscle cramps and weakness that lead to trouble walking.

The condition, which can occur in about two-thirds of patients during chemotherapy, often improves or resolves over time. But the issues can persist for months, even years in about a quarter of patients.

The risk for the chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy also varies by chemotherapy type, with taxanes and platinum-based therapies such as cisplatin and oxaliplatin associated with the highest incidence.

Cryotherapy may be an effective way to prevent or treat this common nerve condition. The approach involves applying extreme cold to the hands and feet — anywhere from -30 to 4 degrees Celsius — during chemotherapy infusions to narrow blood vessels and limit the amount of chemotherapy-laced blood that flows to the fingers and toes. To enhance the effect, clinicians have also experimented with adding hand and foot compression to cryotherapy, a process called cryocompression.

Research to date has largely suggested that cryotherapy can reduce the incidence of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

A 2024 meta-analysis, which included 17 trials and more than 2800 patients with breast, gastrointestinal, and gynecological cancers, found that cryotherapy significantly reduced the incidence of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy overall (relative risk [RR], 0.23), especially among patients undergoing taxane-based chemotherapy.

In another meta-analysis— which included 11 studies and 2250 patients, largely with breast cancer, who received taxanes — cryotherapy led to a significant reduction in the incidence of grade 2 or higher motor and sensory neuropathy (RR, 0.65 for sensory; RR, 0.18 for motor).

“In many studies, patients report an improvement,” Lajos Pusztai, MD, a breast cancer specialist at Yale School of Medicine, in New Haven, told Medscape Medical News. Whether or not the benefit is due to biology or a placebo effect doesn’t really matter because patients report less neuropathy, and that’s what’s important, he added.

Why Limited Uptake?

Despite the growing body of evidence suggesting a benefit, uptake of cryotherapy to prevent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy remains slow in practice.

One issue: awareness of the technique and how to use it are not universal among cancer clinicians, said Chan.

In a survey Chan led, which included 184 oncologists and other clinicians, only about 60% were aware of cryotherapy as a treatment option and less than a quarter recommended it in their practice.

Treatment protocols are also not yet standardized. Key questions — such as how much cooling is enough? what’s the best way to deliver it? and does compression help? — still need to be answered. As such, protocols vary and can include buckets of ice water or commercially available cooling gloves and booties.

Inconvenience may be another reason for slow uptake. Dealing with bags of ice in the infusion clinic, changing them when they melt, helping patients out of cooling gloves and booties if they need to use the bathroom, and other issues adds “a lot of extra work,” Chan said.

But perhaps the biggest barrier to widespread adoption is the lack of definitive phase 3 data showing a benefit. Many studies to date have been limited by small patient size, retrospective design, and lack of control group. And some older studies have reported high patient drop-out rates because of issues tolerating cold therapy.

Without more conclusive data, the latest American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines, published in 2020, say “no recommendations can be made.” Health insurance coverage for cryotherapy as a preventive or therapeutic intervention for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy is not yet widespread and varies among providers, which also limits more extensive use.

Although not yet offered widely, some cancer centers in the US do provide cryotherapy to patients undergoing chemotherapy or as part of clinical trials.

New York University (NYU) and Yale University, for instance, offer cryotherapy during breast cancer infusions. At Yale, patients who opt for it keep their fingers in ice water or wear cooling gloves during infusions, Pusztai said.

Cryotherapy is also used at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, but instead of simply being an option, physicians recommend it to patients with breast cancer. Clinicians are also starting to recommend it to patients with gynecologic cancers, said Mary Anastasio, MD, a gynecologic oncology fellow at Duke.

Although the recommendation is for cooling alone, Anastasio and colleagues are exploring whether compression could help. Some studies show a benefit to combining cryotherapy and compression, while others don’t. And Anastasio’s team is currently conducting a trial to compare cryotherapy alone vs compression alongside cryotherapy in patients women with gynecologic cancers who are receiving infusions of paclitaxel or cisplatin.

At NYU, Sarah Mendez, RN, has also seen cryotherapy work for patients with breast cancer.

Many of these patients “have not been developing peripheral neuropathy, which has been great, and the majority of them tolerate [cryotherapy] really well,” said Mendez, an oncology nurse specialist at NYU. “Ice in a bucket is all you need.”

In a new study, Mendez is exploring whether that benefit can extend to patients with colon cancer. Mendez and colleagues will compare neuropathy outcomes across 40 patients with colon cancer, half of whom will be randomized to wear gloves with ice packs during oxaliplatin infusions.

Still, Chan explained, ultimately “we need a large trial to demonstrate efficacy.”

To that end, the SWOG Cancer Research Network is now recruiting almost 800 patients with solid tumors undergoing taxane chemotherapy for a large, phase 3 randomized trial that will compare peripheral neuropathy outcomes across three study arms: cryocompression, compression alone, and low-pressure compression.

Overall, though, the available evidence does suggest that cryotherapy is “really low risk” and patients often report improvements, so “I think it’s worth trying,” Pusztai said.

Anastasio, Mendez, and Chan have no disclosures. Among other industry ties, Pusztai is a consultant and/or researcher for AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Pfizer.

M. Alexander Otto is a physician assistant with a master’s degree in medical science and a journalism degree from Newhouse. He is an award-winning medical journalist who worked for several major news outlets before joining Medscape. Alex is also an MIT Knight Science Journalism fellow. Email: [email protected].

Source link : https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/cryotherapy-chemotherapy-neuropathy-does-it-work-2025a100069v?src=rss

Author :

Publish date : 2025-03-14 20:13:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.