Your limits when exercising really could be all in your head

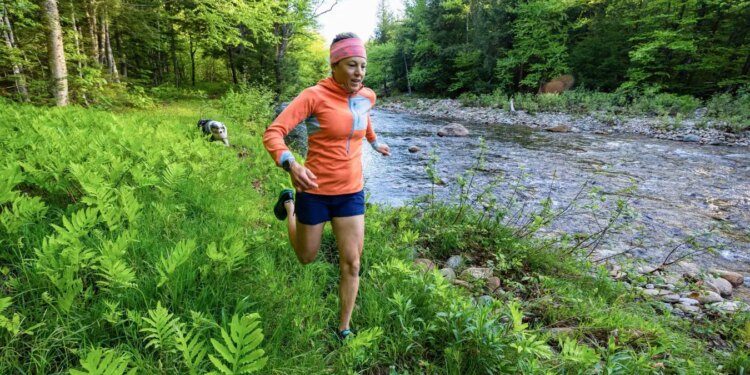

Cavan Images/Alamy

Researchers have identified neurons in mice that help build endurance after running. They suspect that similar cells exist in people, which could be targeted with drugs or other therapies to amplify the effects of exercise.

We have known for decades that the brain changes with physical activity. Yet scientists widely believed these effects are distinct from those occurring elsewhere in the body, like muscles growing stronger, says Nicholas Betley at the University of Pennsylvania. The latest findings suggest otherwise – the brain changes “are what coordinates all that other stuff”, he says.

To better understand how exercise influences the brain, Betley and his colleagues monitored neuronal activity in mice before, during and after treadmill exercise. They zeroed in on cells in the ventromedial hypothalamus, as previous research has shown that impaired development in this brain region hinders fitness improvements in rodents. The same is probably true in people, because the region’s structure and function tends to be consistent across mammals, says Betley.

The team found that after the mice had run, activity increased in a group of neurons with a receptor called SF1, which plays a role in brain development and metabolism. What’s more, the proportion of these cells activated by exercise grew with each additional day of running. By day eight, running activated about 53 per cent of the neurons compared with less than 32 per cent on day one. “So, just like your muscles build when you’re exercising them, your brain activity builds,” says Betley.

Next, the researchers used optogenetics – a technique that activates or inhibits neuronal activity with light – to turn off these neurons in a separate group of mice. The animals trained on a treadmill five days a week for three weeks. After each session, the neurons were inhibited for one hour. At the end of each week, the mice completed an endurance test, running to the point of exhaustion.

Over the course of the experiment, the mice increased the distance they ran on these tests by about 400 metres, on average, but this was roughly half the improvement seen in another group of mice whose neurons were left intact.

It isn’t clear what the role of these neurons is, but it may relate to fuel utilisation, says team member Morgan Kindel, also at the University of Pennsylvania. During endurance activities, the body fuels itself with fat, as carbohydrate stores deplete more quickly. But inhibiting these neurons in the mice led them to “start using carbs a lot earlier on in the run”, says Kindel. “Then, they are kind of out of fuel.” The team found that inhibiting these neurons prevents the release of a protein called PGC-1 alpha in muscles, which helps cells use fuel more efficiently. These neurons also release a substance that increases blood sugar and replenishes energy stores, aiding muscle recovery.

Optogenetics requires invasive brain surgery, so isn’t feasible in people. But it may be possible to develop other interventions that could act on these neurons, says Betley. “I really do think that if we could find a way – a salt, a supplement – to activate these neurons, you can increase endurance,” says Betley.

When the researchers repeated the experiment, boosting rather than inhibiting activity in these neurons, they found just that: the mice developed Herculean endurance, running more than double the distance of control mice.

A similar intervention could particularly benefit people who have difficulty exercising, such as older adults or those who have had a stroke, says Betley.

But there are many hurdles in the way. For one, we don’t know for sure if these findings translate to people. There is also the question of potential side effects, says Thomas Burris at the University of Florida. These neurons seem to regulate energy uptake in muscles, so stimulating them too much could cause a dangerous drop in blood sugar, he says.

Even if we can safely activate these neurons in people, it won’t be a silver bullet for good health, says Betley. “All sorts of great things happen when you exercise – you’re less depressed, less anxious. There are cognitive improvements, cardiovascular improvements, muscle improvements,” he says. “I don’t think that activating [these] neurons is necessarily going to be the bottleneck through which all of those good things happen.”

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2515496-endurance-brain-cells-may-determine-how-long-you-can-run-for/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2026-02-12 17:05:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.