[ad_1]

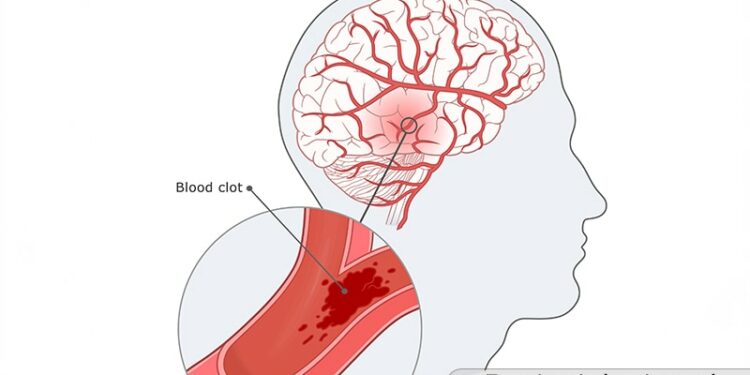

First-time transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) may be associated with a long-term cognitive decline on par with stroke survivors, potentially overturning conventional beliefs about the neurologic impacts of TIAs, according to investigators.

These findings suggest that healthcare providers should be conducting cognitive screening in patients who have experienced their first TIA, Victor A. Del Bene, PhD, an assistant professor at The University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine, and colleagues reported.

“Stroke increases the risk of cognitive decline and dementia; however, compared with stroke, the relationship between TIA and vascular cognitive impairment is less well understood,” the investigators wrote in the February 10 issue of JAMA Neurology.

To explore this relationship further, Del Bene and colleagues conducted a secondary analysis of data from 16,203 participants in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study. The cohort included 356 individuals who experienced a first-time TIA, 965 individuals who had a first-time stroke, and 14,882 asymptomatic control individuals.

Cognitive function was assessed every 2 years using verbal fluency and memory tests, including the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Word List Learning, Word List Delayed Recall, letter fluency, and animal naming tasks.

The primary outcome was a standardized cognitive composite score, with secondary outcomes assessing specific domains of cognitive function.

To distinguish the effects of TIA from preexisting cognitive decline or other vascular risk factors, the investigators used segmented regression models. These models allowed them to compare the cognitive trajectories of individuals before and after their cerebrovascular event, controlling for demographics, education, and vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation.

Before their first TIA, participants exhibited cognitive trajectories like those exhibited by asymptomatic control individuals. But after experiencing a TIA, the rate of cognitive decline accelerated significantly. The annual cognitive decline rate among patients with TIA vs control individuals was −0.05 vs −0.02 SDs per year (P = .02). Of note, the decline observed in the TIA group was not statistically different from the decline seen in stroke survivors, who experienced a cognitive deterioration rate of −0.04 per year (P = .43).

The cognitive impairment observed in patients with TIA was primarily driven by declines in immediate and delayed memory recall, rather than verbal fluency. This suggests that TIAs may selectively impact memory-related brain regions, though the underlying mechanisms remain uncertain.

Findings Challenge Long-Held Notions of TIAs

In an accompanying editorial, neurologists Eric E. Smith, MD, MPH, a professor at the University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and Babak B. Navi, MD, an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York City, argue that these findings challenge the traditional notion that TIAs are benign events with no lasting consequences.

“TIAs are far from benign and should instead be considered potential harbingers of progressive cognitive decline,” they wrote.

Their editorial noted that this new study addresses many of the limitations of previous research by using a large, diverse cohort, long follow-up period, and rigorous adjudication of TIA and stroke events.

Still, the exact mechanisms driving post-TIA cognitive decline remain poorly understood.

“The authors speculate that beta-amyloid and tau pathology could be present, that gamma-aminobutyric acid transmission could have been disrupted, or that blood-brain barrier opening could have promoted neuroinflammation,” Smith and Navi noted.

“Interestingly,” they went on, “a similar phenomenon of accelerated cognitive decline has been seen after systemic vascular events, such as myocardial infarction. This raises the possibility of other mechanisms, including systemic inflammation, and post-event anxiety or depression.”

These findings have immediate implications for clinicians managing patients with TIAs, according to Smith and Navi. Given the elevated risk for cognitive decline, physicians should not view TIAs as isolated, transient events but rather as markers of potential long-term neurologic impairment.

“Stroke-prevention specialists and primary care practitioners should question patients with TIAs, and ideally an informant such as a spouse, about the presence of cognitive symptoms and be prepared to do a cognitive screen for impairment,” they recommended. “TIA should now be viewed as a risk marker for cognitive decline as well as a risk marker for adverse vascular events.”

Smith and Navi stressed the need for further research to elucidate the mechanisms linking TIA to cognitive impairment. Possible avenues of investigation include examining neuroinflammatory markers, assessing subtle structural brain changes using advanced imaging, and exploring potential interactions with neurodegenerative processes, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Understanding these mechanisms could inform future therapeutic strategies aimed at reducing post-TIA cognitive decline, they predicted.

The investigators reported funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Aging, and the McKnight Brain Research Foundation. Navi reported receiving personal fees from MindRhythm.

[ad_2]

Source link : https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/first-time-tias-linked-long-term-cognitive-decline-2025a10003ir?src=rss

Author :

Publish date : 2025-02-11 11:59:05

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.