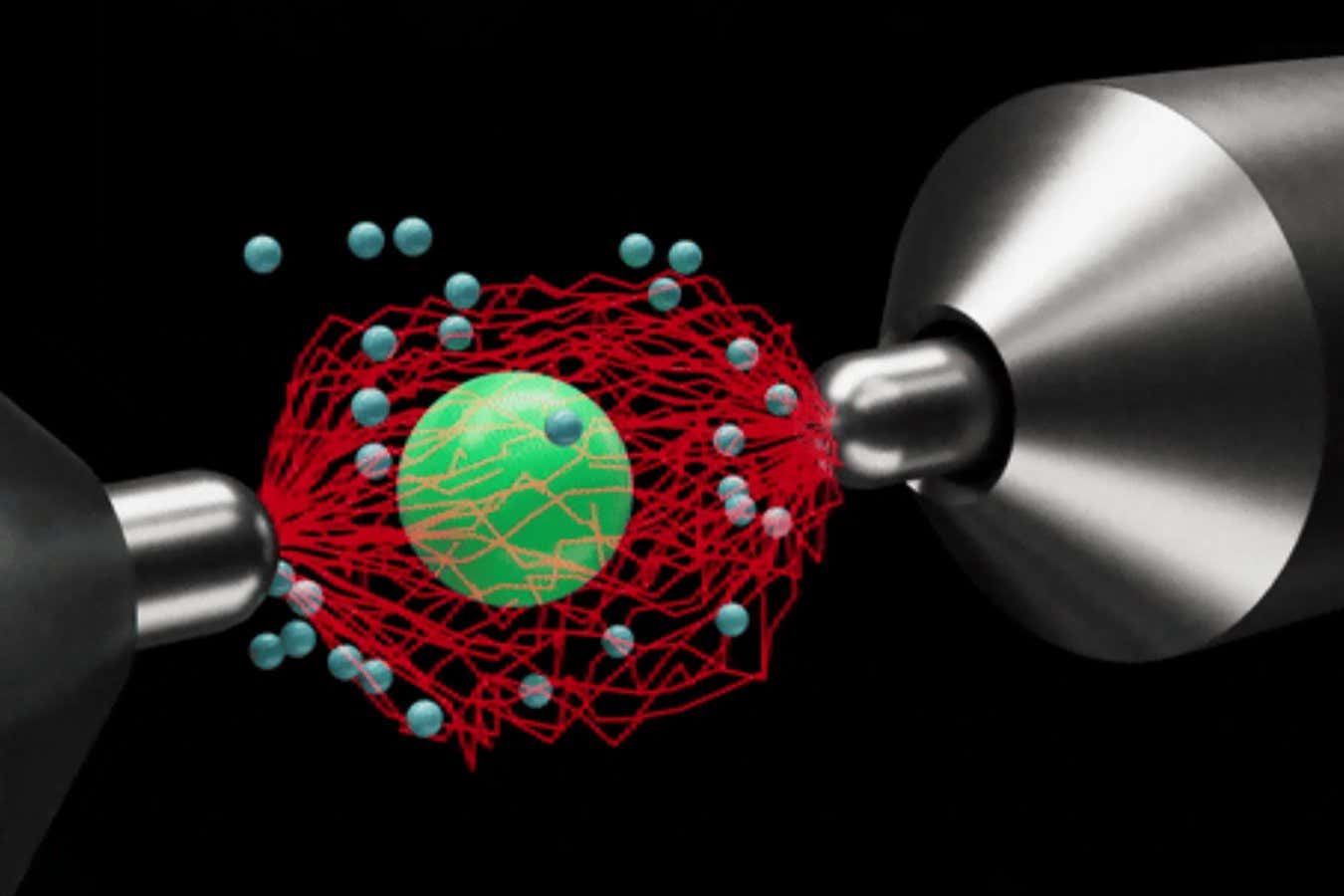

An artist’s representation of the extreme engine

Millen lab

The hottest engine in the world is minuscule, reaches seemingly impossible efficiencies and could approximate nature’s tiniest machines.

A thermodynamic engine is the simplest machine that can reveal how the laws of physics dictate the transformation of heat into useful work. It has a hot part and a cold part, which are connected by a “working fluid” that contracts and expands in cycles. Molly Message and James Millen at King’s College London and their colleagues built one of the most extreme engines ever by using a microscopic glass bead in place of the working fluid.

They used an electric field to trap and levitate the bead in a small chamber made from metal and glass that was almost completely devoid of air. To run the engine, they changed the properties of the electric field to tighten or loosen its “grip” on the bead. The very few leftover air particles in the chamber acted as the engine’s cold part, while controlled spikes in the electric field played the hot part. These spikes made the particle briefly move far more rapidly than the very few air particles surrounding it. Because hotter particles jiggle faster – for instance, in a gas – the glass particle here behaved as if its temperature had momentarily risen to 10 million Kelvin, or around 2000 times the temperature of the sun’s surface, although it would have been cool to touch.

This glass bead engine operated in a highly unusual way. During some cycles it seemed to be impossibly efficient, with the glass bead moving faster than expected given the strength of the electric field. This meant the engine effectively put out more energy than was input. But during other cycles, the efficiency became negative, as if the bead was cooling down under conditions that should have made it extra hot. “Sometimes you think you’re putting in the right energy, you’re putting the right mechanisms in to run a heat engine, and you end up running a fridge,” says Message. The bead’s temperature also varied based on its position within the chamber, which was unexpected because the engine was built so the bead would have either the temperature of the engine’s hot or cold part.

These oddities could be chalked up to the engine’s size: it was so small, even a single air particle randomly hitting the bead could radically change the engine’s functioning – including momentarily turn it into a fridge, says Millen. Traditional laws of physics, which would forbid such behaviour, hold on average, but extreme events still abound. Millen says the same is true for microscopic components of cells. “We can see all these odd thermodynamic behaviours, which are totally intuitive if you’re a bacterium or a protein, but just unintuitive if you’re a big lump of meat like us,” he says.

Raúl Rica at the University of Granada in Spain says the new engine does not have an immediate technological application, but it could help researchers understand natural, biological systems more deeply. It is also a technical achievement, says Loïc Rondin at Paris-Saclay University in France. The team could explore many unusual properties of the microscopic world with a relatively simple design, he says.

“We have a huge simplification of what would be a biological system where we can make tests to validate some theory,” says Rondin. Going forward, the team wants to use the engine in this way, for example to model how a protein’s energy changes when it folds.

Journal reference: Physical Review Letters, in press

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2493968-hottest-engine-in-the-world-reveals-weirdness-of-microscopic-physics/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-08-29 13:10:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.