End-of-life medical care poses many dilemmas for hematologists as they consider treatment for their dying patients. Where do the wishes of patients and their loved ones fit in? Is home care the best option? Is hospice appropriate, even though transfusions are unlikely? Should patients in their final days be taking anticoagulants?

Here are some lessons from a pair of hematologists who offered guidance on these topics in a session last month at the American Society of Hematology (ASH) 2024 Annual Meeting:

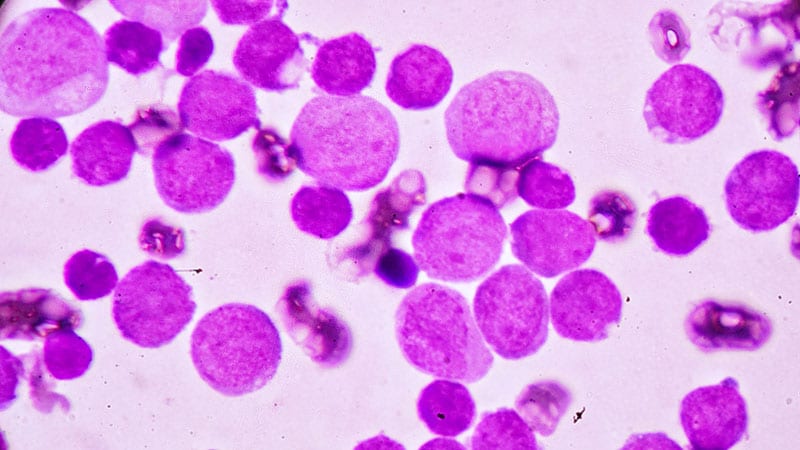

• Blood Cancer Patients Often Don’t Get the End-of-Life Care They Want

“Studies have shown that healthcare utilization at the end of life is high, and patients receive aggressive medical care that may not align with their goals and wishes, especially in the older adult population,” said Melissa Loh, MBBCh, MS, a geriatric hematologist at the University of Rochester Medical Center in upstate New York.

“Conversations about goals of care are often delayed. Generally, there’s a lack of involvement of palliative care and hospice. When they’re involved, it’s often late in the patient’s disease course, when they’re about to die,” she said.

At Loh’s institution, a 2021 study found that just 15.6% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia died at home vs 79.7% in the hospital, and 36.8% received life-sustaining treatment in the last month of life. Just 46.1% were enrolled in hospice, and 60.3% received a palliative care visit. Numbers for patients with myelodysplastic disorders were similar.

Completion of portable medical order forms at least 30 days before death were associated with higher hospice usage (odds ratio [OR], 2.69; P P P

• Home May Not Be the Best Place to Die

An audience member at the presentation noted that deaths at home in blood cancer can be gruesome, especially when graft-vs-host disease is present in transplant patients.

“I’ve become very skeptical of the idea of dying at home for patients with hematologic malignancies,” the speaker said. “The death and dying process is not what it looks like on TV — someone dying peacefully at home with their family at the bedside. With graft-vs-host disease, it looks very, very nasty.”

Loh responded by saying that “I don’t think a good death necessarily means dying at home. It’s very personalized.”

Ideally, she said, models of care will not be limited by location. “For example, hospice can follow wherever people are, and they don’t have to be at home. We have a lot of work to do to figure out the quality metric that we’re trying to achieve here, and that may not mean dying at home.”

• Transfusion Often Isn’t Available In Hospice Care

Transfusions can improve symptoms at end of life, but many hospice programs don’t offer it. “Hospice generally requires patients to forgo cancer directed treatments, which includes stopping transfusion,” Loh said.

She highlighted a 2022 survey of 113 US hospice providers that found 55% never offered transfusion, 41% offered it sometimes, and just 3% always offered it.

“The system is also constrained due to the fixed reimbursement rate for hospice services,” Loh said. “In 2023 for example, the home hospice daily reimbursement rate was about $211, and the cost for one blood transfusion alone is $634.”

ASH supported transfusion access in hospice in a 2019 statement, and federal legislation seeks to provide funding for transfusions outside the hospice bundled payment system.

• It’s Unclear When to Stop Anticoagulants at the End of Life

“We have a lot of guidelines that cover when to start anticoagulants, but they’re conspicuously lacking for when and how to stop them,” said Anna Parks, MD, a nonmalignant hematologist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. In her field, “these decisions are really challenging because studies that specifically target this patient population are few and far between, unlike hematologic malignancies and solid tumors,” she said.

Research suggests that “although anticoagulation is started or continued in a substantial proportion of hospice patients and patients with limited life expectancy, there’s potentially uncertain benefit,” Parks said. That’s because the risk for bleeding can outweigh the benefit of clot prevention.

When clinicians consider whether to continue anticoagulation, Parks noted, they should take into account such factors as life expectancy, the expected time to benefit (how long it may take for the patient to avoid, say, a stroke), and the expected time to an adverse bleeding event. In addition, “they should be thinking about what the risk factors for bleeding are and how the bleeding risk is highest with the initiation of anticoagulant,” she said.

Finally, the decision about anticoagulation should consider patient wishes, she said.

“There’s a ton of diversity in the type of care that patients want near the end of life that you don’t know about until you ask,” she said. “Some patients are willing to accept virtually any treatment, no matter how burdensome to prolong life. Some would accept certain tradeoffs in quality of life for more time, and some would prize quality above all else, including survival.”

In another complication, she said, “qualitative studies have shown that with advancing illness, some patients become less willing to accept burdens of treatments to avoid death, while others become more willing to undergo invasive therapies for any chance of improved health.”

Loh and Parks had no disclosures.

Randy Dotinga is an independent writer and board member of the Association of Health Care Journalists.

Source link : https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/how-blood-cancer-specialists-care-dying-patients-2025a100026n?src=rss

Author :

Publish date : 2025-01-29 07:51:02

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.