Jane Goodall transformed our understanding of chimps

Europa Press Reportajes/Europa Press/Avalon

Jane Goodall, who has died aged 91, changed the world through the way she saw animals, particularly chimps.

In 1960, when she was 26, she observed a chimp she had named David Greybeard fishing for termites with a twig he had stripped of leaves. “At that time,” she later said, “it was thought that humans, and only humans, used and made tools. I had been told from school onwards that the best definition of a human being was man the tool-maker – yet I had just watched a chimp tool-maker in action.”

She reported her finding to her mentor, the palaeoanthropologist Louis Leakey, who sent a famous telegram in reply: “Now we must redefine ‘tool’, redefine ‘man’, or accept chimpanzees as humans.”

In the end, we chose the middle option and looked for some other thing that we could do that other animals couldn’t. But Goodall’s work was vital to undermining the view of human exceptionalism and superiority that had prevailed not just among scientists but in society as a whole.

Goodall in the television special Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees, filmed in Tanzania and originally broadcast on CBS in December 1965

CBS via Getty Images

Her work took aim at the assumption of the French philosopher René Descartes that had propped up the exploitation of animals and the destruction of the environment for 400 years. Descartes said animals have no soul and can be considered machines for us to use as we will. Goodall showed that chimps had the intelligence and foresight to design and build tools, but she also ascribed them emotions and personalities. Some were calm, like David Greybeard, others timid, curious or feisty.

In this, her worked echoed that of another world-changing scientist with similarly brilliant observational powers. In his book The Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Charles Darwin attempted to explain the evolution of facial expressions, ascribing them to emotional states: jealousy, rage, love and so on. But he did so in animals as well as humans, and the establishment rejected it.

The book was poorly regarded at the time and neglected for more than 100 years. Goodall’s work in the 1960s was also initially dismissed and even scorned. It didn’t help that she was a young woman with no degree. Both Darwin and Goodall were driven by unquenchable curiosity and a power of patient, intense observation – and these qualities underlie their success. (When New Scientist once asked her what young scientists need, she replied, “Patience, in huge oodles and bucketfuls.”) We now understand that both Darwin and Goodall were right: many animals have feelings, emotions and inner lives.

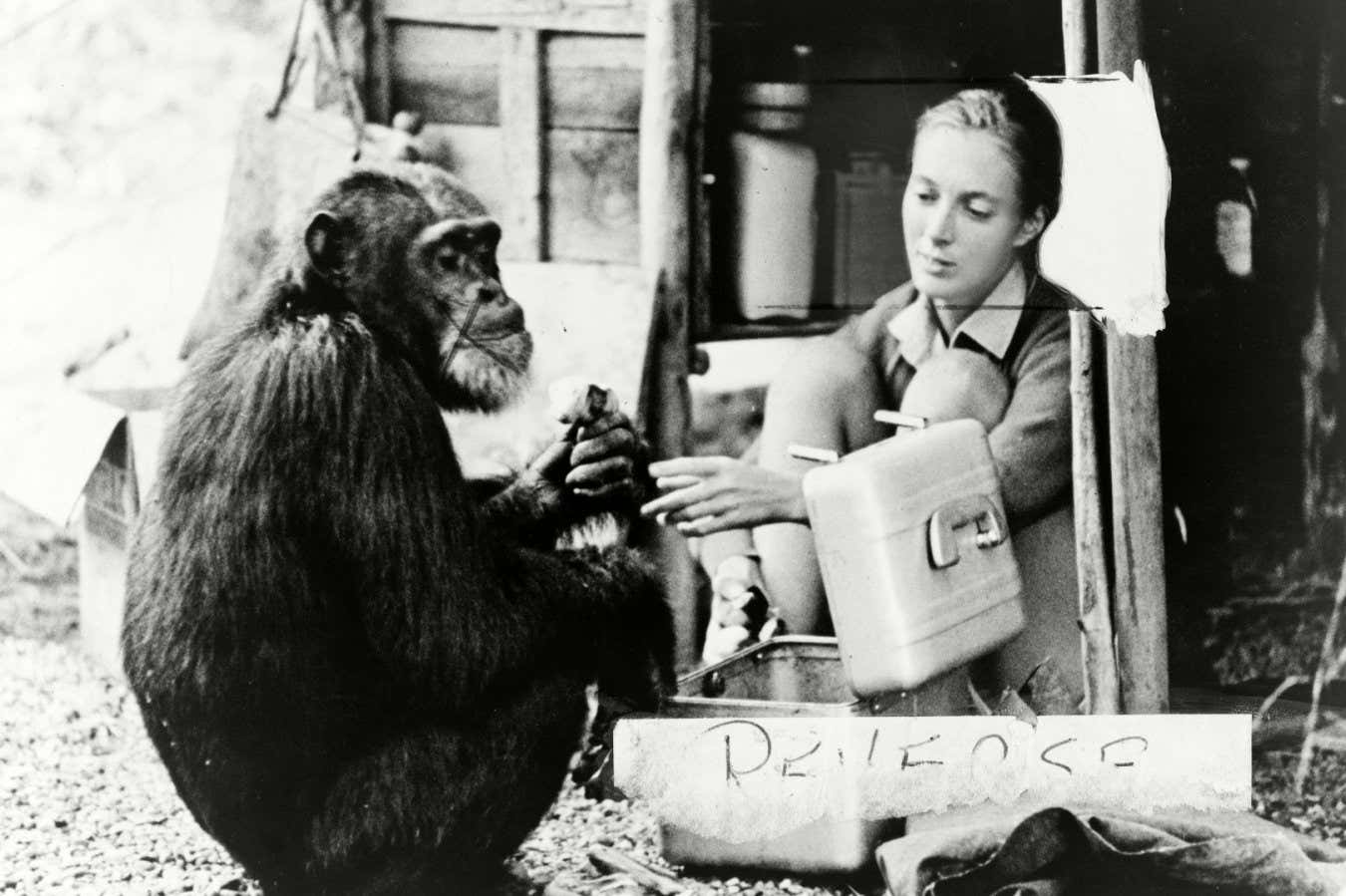

Goodall with the chimp she named David Greybeard in 1965

Granger/Shutterstock

Goodall was chosen by Leakey to study chimpanzees at Gombe in what is now Tanzania. Leakey was interested in understanding human evolution and deducing the behaviour of the common ancestor of chimps and humans, and he decided that studying wild chimpanzees, which no one had ever done, would be a good way to go about it. He wanted someone who was unbiased by established scientific thinking, and he believed a woman would make a more patient, empathetic field biologist. It is unlikely that a trained biologist would have made the breakthroughs that Goodall did.

At first, her observations of chimps were distant glimpses, through binoculars. But gradually she won their acceptance. The first to trust her was the one she called David Greybeard, a male with white hairs on his chin. (She would later, taking a PhD at Cambridge, be reprimanded for giving the animals names and not numbers, but to her it was natural to name them all.) She saw David Greybeard stripping leaves from a twig and then using it to fish termites from a termite mound, and reported her findings to Leakey. “David Greybeard and his tool using was the moment that changed everything,” she later said.

She was also the first scientist to make descriptions of chimp courtship and mating rituals, of their reproductive cycles, and of how mothers introduce their babies to the troop – experienced mothers, Goodall found, calmly allowed the others of the troop to see the baby, whereas first-time mothers hid the baby, provoking hooting and mayhem in the troop.

Goodall at UNESCO headquarters in Paris, France, in February 2018

AGENCE 18/SIPA/Shutterstock

In the 1970s, the focus of her life began to change, moving from observing chimps to championing them. So began her second phase of changing the world. She established the Jane Goodall Institute in 1977, which became a vast non-profit conservation organisation, with offices in 25 countries. In 1986 she organised a conference for field biologists working on chimps at sites across Africa, and it drove home the threat facing the animals and the forests they rely on. She also learned about the problems facing people who live near the chimps’ habitats.

In 1991 she started Roots & Shoots, an organisation aimed at teaching young people about conservation. It is active in over 75 countries. Constantly touring and speaking on conservation, she gave around 300 public appearances a year. In 2024, she visited each of the offices of the Jane Goodall Institute to speak to the media about conservation work and the rights of animals.

Goodall died in California, in the middle of a speaking tour. She wrote 32 books, including 15 for children. In her final one, The Book of Hope, she wrote: “I realised that if we couldn’t help people find a way of making a living without destroying the environment, there was no way we could try to save the chimpanzees.”

Goodall spoke of the influence of another of the 20th century’s most important figures, the ecologist and conservationist Rachel Carson. At the University of Cambridge in the 1960s, she said, “I read Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and was inspired by her courage in battling with pharmaceutical companies, the government and scientists about the danger to the environment of DDT.”

Carson knew there was a long fight ahead but never gave up and will continue to inspire, she said. The same is true of Jane Goodall.

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2498651-how-jane-goodall-changed-the-way-we-see-animals-and-the-world/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-10-02 11:02:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.