When I usually examine lichens, I am in a forest, peering at frilly growths on tree branches with my hand lens. Or on exposed rocks high in the Alps, or old gravestones, or the rocky seashore, in the zone where the seaweed stops growing but before bigger land plants take over. I have been looking at a lot of lichens during research for a book on symbiosis, but where I have never seen them before is in a lab flask swirling in an incubator. And while I often think about what lichens tell us about the past, I hadn’t until recently thought about what they tell us about the future.

The green cloudy fluid I am looking at in the incubator is not at all what we think of as a lichen, which is a symbiotic partnership between a fungus and an alga. “That’s because this is a synthetic lichen,” says Rodrigo Ledesma-Amaro, who is the director of the Bezos Center for Sustainable Protein here at Imperial College London. The fluid is a co-culture of two species, a fungus (yeast) and a cyanobacterium. Like a natural lichen, the fungus provides a scaffold, a host structure for the bacterium, and the bacterium makes sugars through photosynthesis using light, water and carbon dioxide, and feeds them to the fungus.

Why on earth would you want to make such a potion? Because, Ledesma-Amaro tells me, we can gene-edit yeast to get it to create all sorts of useful products – food, fuels, chemicals, materials, pharmaceuticals – and if we can drive that production through photosynthesis, then we can make those things sustainably. For that reason, synthetic lichens are sparking excitement not only in the biotech industry but also beyond it. Lichens, it transpires, could be harnessed to repair buildings, fight the climate crisis and even build habitations on Mars.

“Synthetic lichens recreate the symbiosis of natural lichens, but grow much faster, and using yeast as a partner allows us to sustainably produce a whole range of high-value compounds,” says Ledesma-Amaro. Yeast is a well-known, industrialised organism that is “programmable” and easily grown at scale. In the synthetic lichen I see, Ledesma-Amaro and his team use yeast that is genetically engineered to make caryophyllene, a compound that has applications in the pharmaceutical, cosmetic and fuel industries. In the near future, he foresees a range of useful products: antibiotics, biofuels and synthetic palm oil. Another form of synthetic lichen might be engineered to capture and store carbon dioxide. Other scientists see lichens being deployed to repair ageing concrete structures around the world. The ambitions for lichens are high, even reaching beyond our own planet. On the moon and on Mars, NASA and private space companies plan to use synthetic space lichen – properly known as an engineered living material – to grow on regolith and make material for constructing buildings and furniture.

Living together

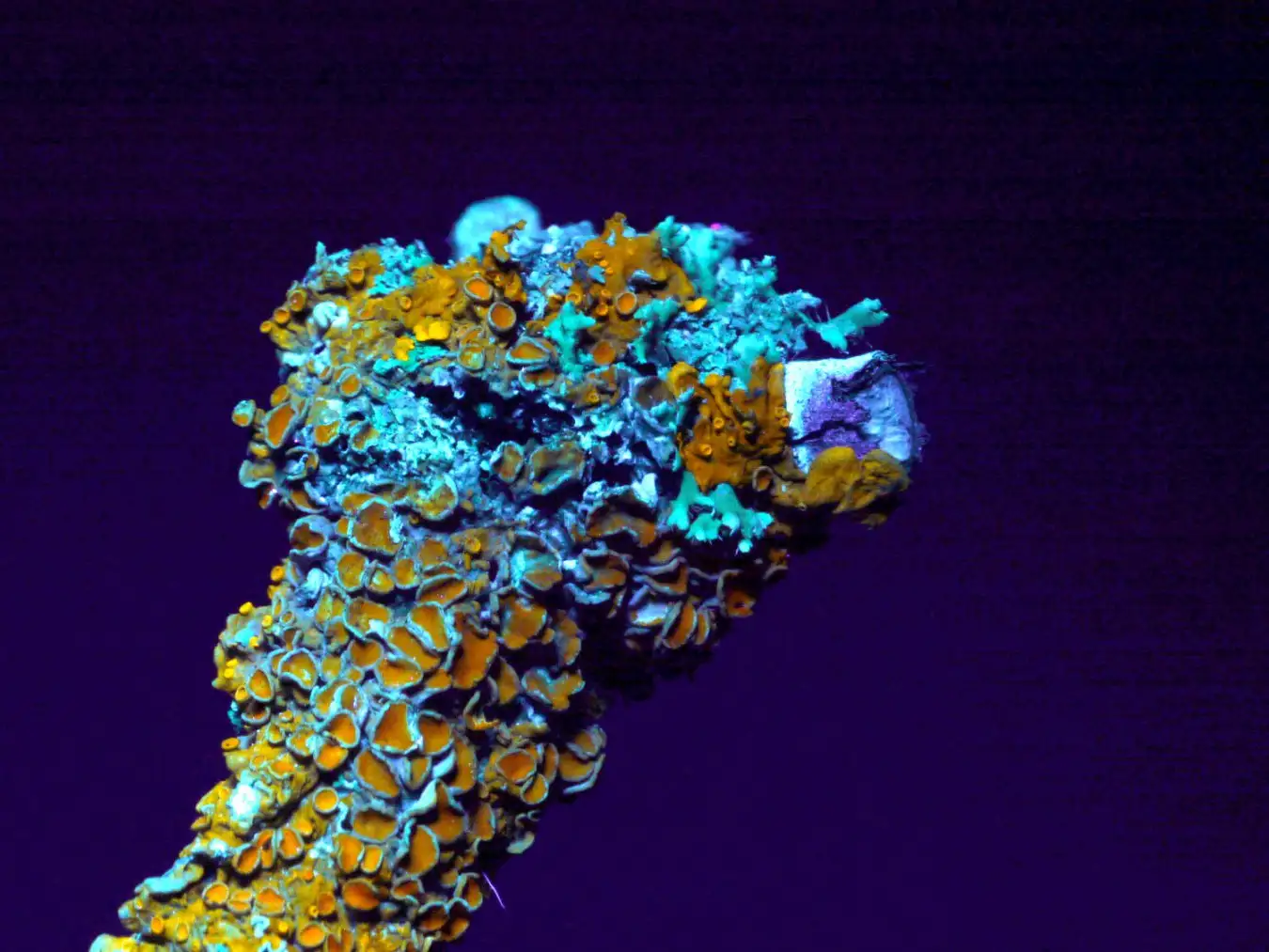

Modest in appearance and slow in growth, lichens are the archetypal demonstration of symbiosis, which means “living together” and refers to the cohabitation of two different species. In the case of lichen, the textbook explanation is that a fungal partner hosts an individual of another species, known as the photobiont. Usually, this is algal, but sometimes bacterial, and it makes food through photosynthesis and shares it with its host. The fungal partner provides, among other things, superb protection from the elements, such that the lichen can survive in extreme conditions where little else can make a living. This is why some scientists are repurposing lichens and making synthetic versions of their own.

Lichens have two qualities in their favour. First, as a symbiotic organism, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. In other words, each lichen can do things that the fungus alone or the photobiont alone cannot do. From afar, lichens may be modest in appearance, but up close, they are complex, luxuriant, charismatic organisms. Natural lichens are also far more than the textbook two-species partnership of fungus plus alga. Often, there are these two organisms, plus a secondary fungus in the form of yeast and an extra bacterial species, making a community of four. But even that is an underestimate. “In nature, what we call a ‘lichen’ colloquially is actually a community of many – tens to hundreds – of different microbes,” says Arjun Khakhar, a biologist who makes synthetic lichens at Colorado State University. “Two lichens that look identical and are right next to each other can have hugely different members.” Various analyses of fresh lichen tissue have found that they contain between 1 million and 100 million bacteria per gram.

The second thing lichens have going for them is that they are robust. They can live and photosynthesise in the harshest of conditions. In Svalbard, far within the Arctic circle, there are around 700 species of lichen. They cope with low temperatures, aridity and high ultraviolet radiation. On the seashore, they tolerate repeated immersion in saltwater – an experience that most other land plants can’t cope with. Some species grow inside rock (“endolithic” lichen, literally “inside rock”). It is an open question as to just what aspect of their biology allows them to cope with desiccation and extreme temperatures.

Lichens, which naturally thrive in a variety of environments, are a unique lifeform, made from a symbiotic relationship between a fungus and a partner like algae or cyanobacteria

Jose B. Ruiz/naturepl.com

In Colorado, Khakhar suggests lichens’ resilience comes from biomolecules the filamentous fungus produces, which protect the entire community in the lichen. “The unique molecules it is able to make are potentially due to lichens’ capacity to leverage both bacterial and fungal biochemistries via distributing tasks across the community,” he says. For example, components in the photobionts can make various pigments with chlorophyll, and the fungus can make sunscreen by synthesising compounds such as carotenoids (the pigments in carrots, ripe tomatoes and autumn leaves) and melanins (which colour our skin). Together, the symbiotic lichen community has access to a greater range of compounds than a single organism can hope to produce, and this unlocks the lichen’s superpower. Physically, too, the fungal component helps buffer the community from swings in temperature and humidity. Then there’s its slow growth, which allows it to live with minimal resources.

Lichens in space

These attributes have been enough to get NASA excited. Lichens can survive exposure to both simulated and real space conditions. Starting in 2014, a lichen species called Circinaria gyrosa lived – or at least, didn’t die – on a shelf on the exterior of the International Space Station for 18 months. When it was brought back inside and given water, it started growing. The fact that lichens can grow inside rock and tolerate the conditions of space excites proponents of lithopanspermia, the idea that microbes could travel between planets in asteroids.

Congrui Jin, an engineer specialising in living materials at Texas A&M University, started thinking about the potential of lichens for a forward-thinking NASA project aimed at finding efficient ways to build places to live and work on Mars – whenever we eventually get there. Some proposals for off-planet housing rely on inflatable structures, the idea being that fewer materials are needed to make air-filled housing. But every item of prefabricated material transported there by rocket is still expensive. A cheaper alternative to hefting such items up from Earth is to find a way to produce building materials from the regolith already on the planet. For Jin, lichens are the perfect solution. But a naturally occurring species may not necessarily work.

An experiment aboard the International Space Station has shown that lichens can be extremely hardy, surviving for more than 18 months in space

ESA

“We want to pair the fungi with some photosynthetic species like cyanobacteria. They can convert sunlight and water into organic nutrients and precipitate calcium carbonate,” she says. “It acts as glue to bind the soil particles on Mars into a cohesive structure.” This biomaterial can then be used in a 3D printer to produce building materials – floors, partitions, walls, furniture, you name it. The bulk of what you need, whether sunlight, carbon dioxide, water, nutrients or vast supplies of basalt rock, is already there on Mars.

Jin’s work has recently shown that lichens are promising candidates for turning Mars regolith into building material and for producing other biominerals and biopolymers. Lichens are tough, and some eager futurists consider them good candidates for helping to terraform the Red Planet. But even if there weren’t planetary protection measures to abide by, lichens can’t grow on the surface of Mars, exposed to the elements. Mars has no magnetic field, and any life on the surface needs to be shielded from the harsh radiation. So, Jin envisions her Mars lichens growing in shelters.

The future of building

However, colonising other planets is a long way off, and Jin realised her lichens had a more immediate role on Earth. There are many occasions when it would be useful to bind rubble together and make a usable building material. Think about the wrecked buildings left by natural and human-caused disasters. As well as that, a way to sequester carbon during the concrete-making process would help moderate its huge carbon footprint. And what if we could produce self-healing concrete? Buildings and structures would be cheaper to maintain and would have a longer life, too. Previous attempts to use microbes to perform these functions have faltered because concrete is an inhospitable place in which to live. But if lichens can cope in space, Jin reasoned, surely they can cope with concrete.

Jin and her colleagues showed that a lichen-based approach, pairing fungi with cyanobacteria, makes a co-culture that can grow on concrete. Not only that, her synthetic lichen precipitates calcium carbonate – the mineral that forms chalk, limestone and marble – healing cracks in the structure. “We tried filamentous fungi and cyanobacteria and found that they have better survivability [than other microbes] under the dry and nutrient-poor conditions in concrete,” she says. “They get along with each other and the process is autonomous, and they also have [a] very good capability to precipitate calcium carbonate.” Unlike single-species approaches, the co-culture doesn’t require the addition of external nutrients, because the synthetic lichen extracts nitrogen from the air and makes its own fertiliser.

Khakhar is also attempting to make fast-growing lichen by selecting microbes that are already fast growers, before tweaking them and pairing them to become lichen-like. His lab, in work similar to Jin’s, has made a synthetic lichen in which the fungal component becomes mineralised. “Filamentous fungi are fed by the cyanobacteria embedded in them and grow a mycelium that has a stone exoskeleton,” he says. “In the future, this will enable the sustainable biomanufacture of building materials.” He calls the engineered product mycomaterials.

My investigations of symbiosis have deepened my appreciation of lichens as dynamic mini ecosystems, a living lesson in the reality of interdependence, as has understanding their sci-fi potential in crafting the materials of tomorrow. So the next time you see those frilly growths on a tree, a gravestone or an old bench, perhaps take a moment to pause – and consider what a future-shaping marvel you are beholding.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2506992-how-lab-grown-lichen-could-help-us-to-build-habitations-on-mars/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-12-23 12:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.