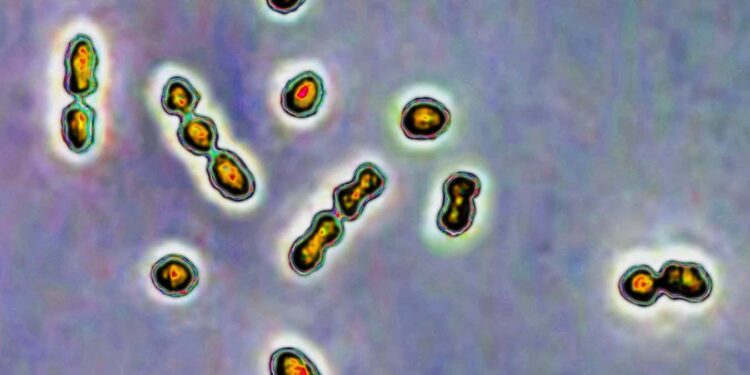

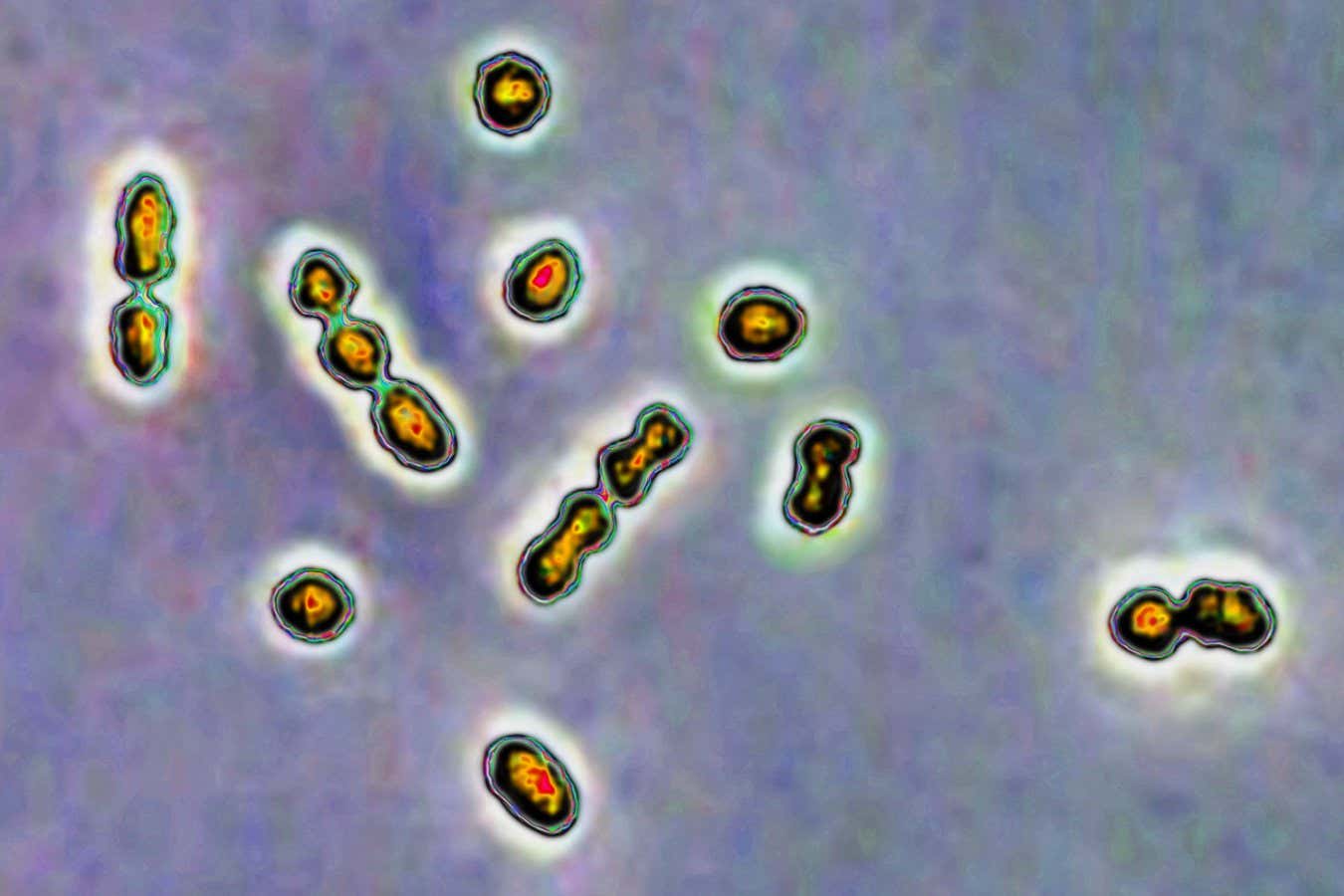

Streptococcus bacteria are responsible for vaginal and urinary tract infections and newborn infections

CAVALLINI JAMES/BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

A type of sugar in human milk could help treat a common strain of Streptococcus bacteria, which can complicate pregnancies when it infects the vagina.

Human milk remains understudied. “This is the second most important liquid in the universe after water, and we don’t know much about it,” says Steven Townsend at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee.

Researchers are just beginning to unpack the properties of helpful sugars found only in this substance: human milk oligosaccharides, or HMOs. Although they were once thought to be random sugars, recent studies suggest they are extremely effective prebiotics, “kind of like personalized medicine” for newborn babies, says Townsend.

Previous studies on HMOs have focused on how they might benefit the gut microbiome. Townsend and his team decided to instead study their effect on the vagina. They wanted to better understand how HMOs may help regulate the proportion of healthy bacteria and potentially dangerous Group B Streptococcus, or GBS.

“Group B Strep is a bacteria that all of us have,” says Townsend. “It typically is going to cause us no harm, and we’re not even going to know we have it.” However, GBS can cause disease in immunocompromised people, including pregnant women and newborn babies. During pregnancy, GBS in the vagina can cause a variety of problems, like preterm birth. For this reason, pregnant people with vaginal GBS infections are typically treated with antibiotics.

Townsend and his team tracked the growth of GBS and healthy Lactobacillus bacteria in the presence of HMOs. They studied three different scenarios: the bacteria and sugars on their own, on lab-engineered vaginal tissue and in living mice. In all three cases, HMOs promoted the growth of healthy bacteria, which outcompeted the GBS.

The result is likely due to a “nice little storm of positive effects”, says Townsend. He explains GBS cannot grow in an environment with HMOs, whereas the healthy bacteria can eat HMOs and grow prolifically, further stifling the growth of GBS. On top of this, as the healthy bacteria consume the HMOs, they produce fatty acids that make the whole environment more acidic, killing even more harmful bacteria.

The finding suggests more ways to potentially regulate and restore a healthy vaginal microbiome. “Anything that points to new tools or methods to do that is of high therapeutic value for women and their newborns,” says Katy Patras at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas. However, she says a potential therapy is still several steps down the road.

Even when a useable therapy becomes available, the researchers say the best course of action to treat a GBS infection is still to take antibiotics. “What we’re doing is not to replace antibiotics,” says Townsend. “We’re doing this research to try to save antibiotics”, because overuse of antibiotics can lead to antibacterial resistance that renders the drugs ineffective. A novel therapy using HMOs to regulate the microbiome could be used in tandem, reducing the amount of antibiotics required to treat GBS.

“I think those synergistic interactions could be extremely useful,” says Lars Bode at the University of California, San Diego. However, he cautions, people should stay tuned for further developments rather than trying to engage with human milk therapy at this preliminary research stage. Doing so could actually create even more problems, as untreated milk can carry infectious diseases like HIV, he says.

In the meantime, Townsend wants to better understand the unique evolutionary tools humans are equipped with in HMOs.

“It’s absolutely mind-boggling how we’ve completely understudied and underestimated the power of human milk,” says Bode.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2490577-human-milk-could-help-fight-infections-that-endanger-pregnancies/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-07-30 21:45:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.