Canada’s Indigenous population continues to face major disparities in heart and stroke care. These disparities result from a combination of neglect, inaccessible resources, and lack of cultural sensitivity when it comes to community values and healthcare practices.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among Canada’s Indigenous population, which includes First Nations, Métis, and Inuit patients. According to a 2022 study in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology, incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates for cardiovascular disease are higher among Indigenous peoples than among non-Indigenous Canadians. First Nations patients have approximately 2.5 times the cardiovascular disease prevalence compared with that of non-First Nations patients.

Complicating the situation, access to and inequality in cardiovascular care for Indigenous Canadians remain poorly studied and understood, the study noted. Isolation in remote communities, lack of access to emergency services, negative past experiences with the medical system, and resulting mistrust are factors contributing to this long-standing and growing healthcare crisis.

“The disparities in care for Indigenous Canadians are due to a mix of historical, systemic, and social factors,” Christine Faubert, vice president of Health Equity and Mission Impact at Heart & Stroke in Toronto, told Medscape Medical News. “The legacy of settler colonialism has left deep scars, creating conditions that lead to significant health disparities. This includes trauma and socioeconomic disadvantages from policies like residential schools and forced relocations.”

Bridging the Cultural Divide

Many patients delay medical care because they’ve had such negative experiences in the past, and this decision often results in advanced disease by the time they seek care, Heather Foulds, researcher and professor of kinesiology at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, told Medscape Medical News. “Also, when patients undergo stroke or cardiac rehabilitation, healthcare practitioners place great emphasis on the individual patient. However, Indigenous communities are much more family-oriented, and the patient might have grandchildren for whom they’re caring and can’t simply leave behind,” Foulds noted. She is a former Heart & Stroke and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Indigenous Early Career Women’s Heart and Brain Health Chair.

“Some patients have 3-day delays following a stroke because there are no healthcare providers. Most rehabilitation centers are in major cities, and patients have no way of getting to them.” Conflicting life priorities also play a role. “A patient might say to themselves, ‘What’s the most important challenge I’m facing today? Maintaining my blood sugar levels might not be the most important thing right now when I’m trying to find a place for my kids to live.’”

In addition, Western and Indigenous views of medicine differ significantly. For Indigenous Canadians, living within a healthcare paradigm so different from their own can be challenging. Some Indigenous community members are carving out their own academic paths as a way of focusing on their people’s distinct needs.

Pathways for Change

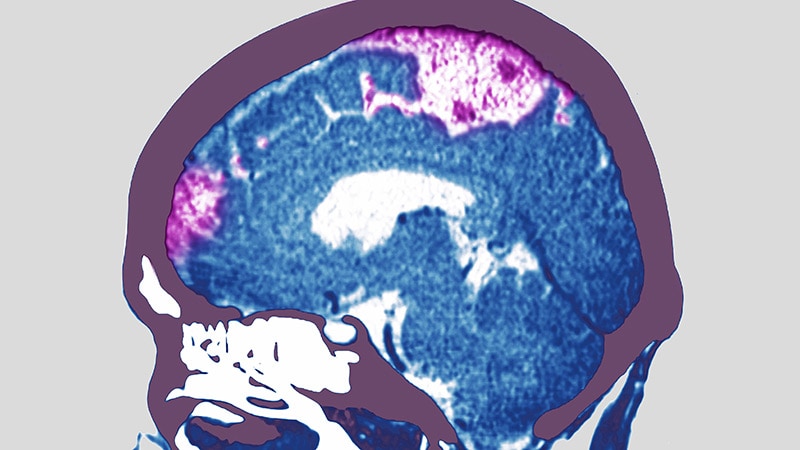

Originally from the Pimicikamak Cree Nation in northern Manitoba, Margaret Hart is a doctoral student in the University of Manitoba’s Faculty of Education, Winnipeg. Hart has been seeking to rebuild the occupational therapy program to incorporate Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing. “Across Canada, First Nations and other Indigenous communities are drawing on generations of knowledge, relational teachings, and community-based values to promote health and well-being,” said Hart. “Due to the historical and ongoing impacts of colonization, many First Nations people face elevated cardiovascular risk and reduced access to timely, appropriate stroke care. We know stroke is a leading cause of death and disability and that women are at higher risk and often experience different pathways of recovery.” Hart’s mother, Phylis, of the Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation, died of a hemorrhagic stroke in September 2024 with no care or prevention.

Heart & Stroke is tackling the challenges of health reconciliation and striving to provide better access to equitable healthcare in culturally safe environments for Indigenous populations. One of their initiatives is StrokeGoRed, which was developed for women in the north who have no access to basic care. It’s the first formal research network in Canada dedicated to studying stroke in women. Together with Hart, they’re working to understand how stroke affects women and men differently and to develop personalized treatments to improve outcomes for women.

In partnership with community members in Whitecap Dakota First Nation, Stacey Lovo, PhD, a researcher with the School of Rehabilitation Science in the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Medicine, has developed a virtual reality hub to provide remote treatment for northern Saskatchewan communities that can’t easily access healthcare. The program will allow patients to be seen much more quickly. “This is a very exciting model of access. It takes place on Dakota First Nation land, so it’s an example of First Nations people taking leadership and ownership of the situation,” said Foulds.

Faubert, Foulds, and Hart reported having no relevant financial relationships.

Evra Taylor is a freelance medical writer and reporter with 20 years’ experience covering a broad range of therapeutic sectors, including family health, cardiology, psychiatry, ophthalmology, and dermatology.

Source link : https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/indigenous-canadians-lack-access-cardiologic-stroke-care-2025a1000jdn?src=rss

Author :

Publish date : 2025-07-22 11:44:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.