In physics, breakthroughs are rare. Experiments are slow, expensive and often end up refining, rather than rewriting, our understanding of the universe. But what if the only constraint on scientific ambition were imagination?

We asked five physicists to describe the kind of experiment they would do if they didn’t have to worry about budgets, engineering limitations or political realities. Not because we expect any of it to happen soon – though in a few cases, momentum is building – but because it is revealing to see where their minds go when the usual boundaries are stripped away.

One researcher wants to launch radio telescopes deep into space to probe dark matter with cosmic energy flashes. Others are dreaming of completely new kinds of particle accelerator or lasers that push the at bounds of the possible.

Some of these concepts are technically plausible. Others aren’t even close. That’s fine. They still point to the questions that keep physicists up at night, and the kinds of answers they would chase, if only they could.

Radio telescopes in deep space

Huangyu Xiao, Boston University and Harvard University

My dream experiment involves sending radio telescopes into deep space and looking at fast radio bursts (FRBs) – brilliant, millisecond-long flashes of energy from the far reaches of the cosmos. The exact origins of FRBs are mysterious, but they are ideal as a tool for studying dark matter in a wholly new way.

Ideally, we want two different radio telescopes separated by distances tens of times that between the sun and Earth. The telescopes would observe the same FRB and measure the difference in when they see it arrive. The larger separation between the telescopes, the more significant this time difference would be.

We are talking about very expensive, very ambitious space missions that are likely to cost billions of dollars.

Deep space radio telescopes could help us discover dark matter by finding axions, hypothetical dark matter particles. Axions were invented to solve a separate theoretical puzzle, but they may also serve as a dark matter candidate.

A striking prediction of axion cosmology is that they leave fingerprints on the distribution of dark matter on small scales. The only evidence for dark matter so far is its gravitational effect over cosmological distances, which is larger than individual galaxies. Axions create interesting ripples in the dark matter distribution on extremely small scales, such as that of our solar system, which is well beyond current reach. So, a small-scale measurement of dark matter gravity will be the key to discovering its nature.

A muon collider

Jesse Thaler, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

I am an enthusiast for an audacious idea to explore the unknown: a muon collider.

Audacity has often fuelled progress in my field of particle physics. In 1954, Enrico Fermi imagined a particle accelerator around the whole planet, which he dubbed the Globatron. But technology has a way of catching up with our dreams, and with just a 27-kilometre ring, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN achieved Globatron-level energies, leading to the Higgs boson discovery in 2012.

The muon is a brilliant candidate for a discovery machine. Muons are 200 times heavier than electrons, which makes them more efficient to accelerate. And unlike the protons used at the LHC, muons are elementary particles, so colliding them together would probe sharper, higher energies, potentially allowing us to discover more massive particles beyond the Higgs boson or even the nature of dark matter.

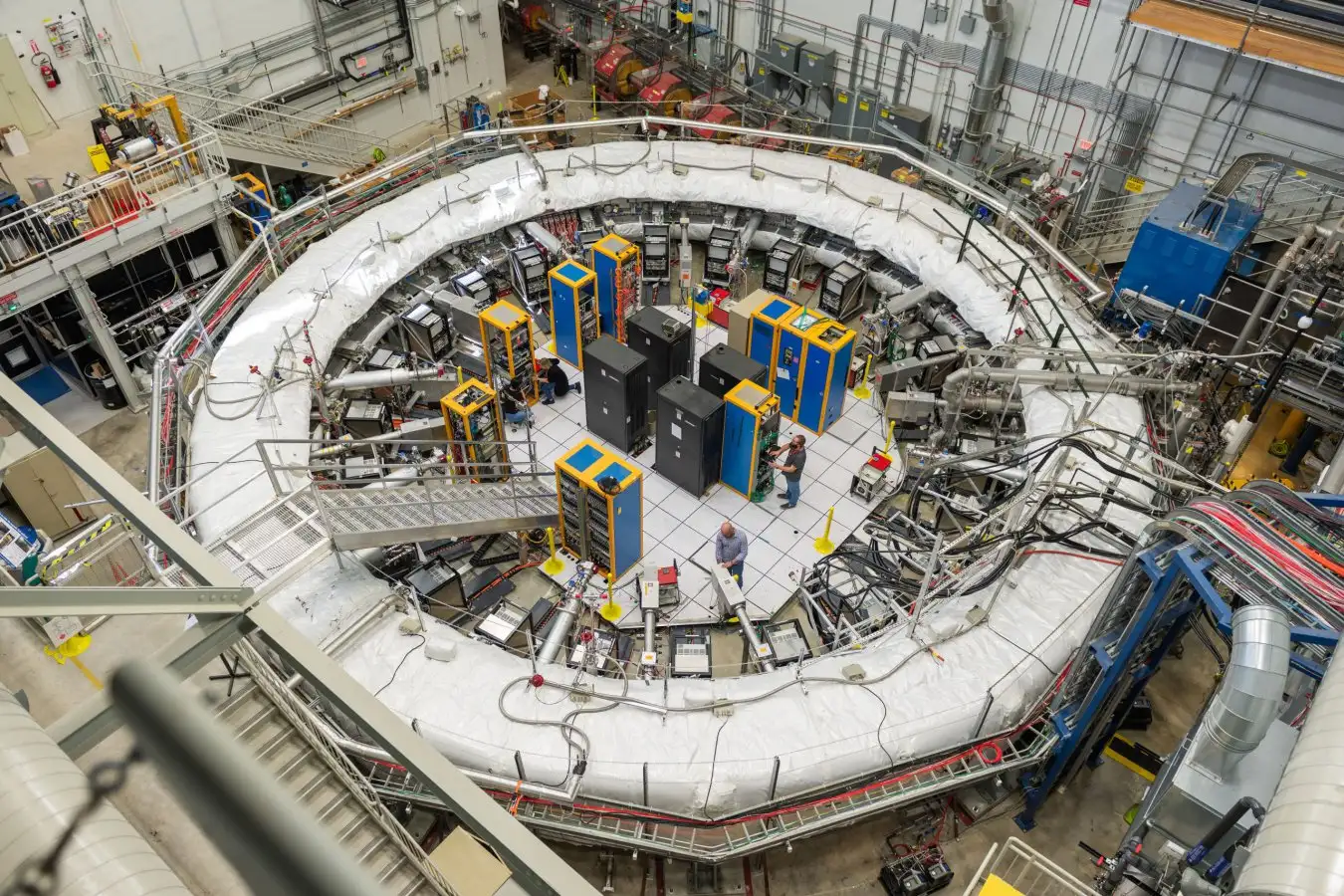

The Muon g-2 experiment at Fermilab accelerates muons, but does not collide them together

But there’s a catch: muons are unstable, decaying in millionths of a second. In that blink, we’d have to create them, contain them, accelerate them close to light speed and then smash them together. Fortunately, as the muons move faster, they appear to exist longer from our perspective, thanks to Albert Einstein’s special theory of relativity, buying us a bit more time. Even so, making it all work would require Fermi’s level of audacity.

A decade ago, I was sceptical that this could ever work. One daunting step in the process is “6D cooling” a diffuse cloud of muons into tight, coherent bunches. Given this and other obstacles, the particle physics community in the US abandoned the development of a muon collider in 2014.

Around 2020, though, a parade of innovations, including a successful muon cooling experiment and a clever design to avoid cooling altogether, started to shift my opinion. Soon after, theorists showcased the immense potential a muon smasher would have to unravel deep mysteries in fundamental physics, like potentially illuminating the nature of dark matter. Momentum quickly gathered to restart the development of a muon collider. In 2023, I co-wrote an official report recommending we pursue the muon collider project. Now, that recommendation has been backed by the US National Academies panel.

Building such a device won’t be easy, and we must balance our blue-sky aspirations with concrete plans for other frontier experiments, like a “Higgs factory“. Yet I find myself increasingly drawn to a muon collider, which, it turns out, would fit perfectly within the footprint of Fermilab, the premier US particle physics laboratory, named after Fermi himself.

Gamma ray laser

Thorsten Schumm, TU Wien

When I was a child, I tried to build my own lightsaber using aluminium foil to direct the light of a torch into a straight line. I admit, the result was questionable at best.

Later, when I became an atomic physicist, I learned about the physics that would have helped my lightsaber work. An atom can store energy by promoting an electron to a higher quantum level and give it back by releasing a photon. In special cases, this photon can be “trained” to go in a very specific direction, at a specific colour, and take other photons with it, in a sort of avalanche of light. Ultimately, what emerges is a very directed, monochromatic beam – or a laser beam.

My dream is to build a gamma laser, something that has never been built before. It would emit a directed beam of monochromatic gamma rays, the most energetic part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Such a gamma laser would work on the stimulated emission of excited neutrons or protons in an atomic nucleus, rather than the electrons surrounding it. It could help us monitor the fine structure constant, a measure of the strength of electromagnetism between particles. The size of this constant is one of physics’ biggest mysteries.

While conceptually simple, realizing this dream is a tremendous challenge, as nuclear quantum excitations occur at much higher energies than those of electrons. No mirrors or lenses can bend or focus gamma rays; they just travel straight through.

To get around this, we work with a very special nucleus, called Thorium-229. Out of the about 3500 known isotopes, it has the lowest-energy excited state of a neutron, only a little higher than the energy stored in excited electrons in atoms. So, we can use standard tools from atomic physics to play with it.

Thorium-229 is extremely rare; there are just a few grams available on this planet. It has a finite lifetime of about 8000 years, which makes it mildly radioactive. All in all, it is difficult to come by and work with. Over the past 15 years, we have learned to handle it: we are now able to fuse it into artificial crystals, so it can be used in optical experiments.

In 2023, we managed for the first time to promote the outermost neutron of Thorium-229 to the excited state and detect the gamma ray that is released when it returns to its ground state. To excite the neutron, one needs to expose the nucleus to a periodic signal of a very high and precise frequency – 2 million billion oscillations per second. Counting these oscillations creates a kind of “nuclear clock”, which we implemented in 2024.

What’s missing to realise the gamma ray laser is to trigger the avalanche effect in stimulated gamma emission of excited nuclei. For this, we plan to combine the Thorium crystals with optical resonators, bending the gamma rays into a focused beam. Then, we can proceed to nuclei with higher-energy excited states.

Penrose minds

Abhishek Banerjee, Harvard University

Quantum computers are on the brink of a scale crisis. The bulk of today’s devices can manipulate around 100 qubits – barely enough to run even simple problems. But to reach the power needed for practical breakthroughs, we’ll need to scale to millions. And that’s where things get difficult.

Most systems rely on superconducting qubits kept just above absolute zero. But they also need to talk to classical chips that run at room temperature. Shuttling information back and forth across this steep thermal divide slows everything down – a problem that gets worse as we scale up.

This is the problem I’ve been trying to solve.

I work on new superconducting hardware that lets quantum and classical components live side by side, on the same chip. Instead of bouncing data between hot and cold zones, this setup brings them together in what’s called a hybrid quantum-classical architecture. It’s tighter, faster, more efficient – and it could let us finally scale.

But while building these systems, I have started wondering if something stranger might be emerging.

I’ve been working on this for years. But only recently, while describing the idea to a fellow passenger on a flight, something clicked. The architecture I was sketching out resembled a theory I had once read during my PhD, in a book by physicist Roger Penrose.

Penrose had a bold idea: that the mysterious thing we call a “mind” might emerge at the boundary where quantum uncertainty meets classical reality. He speculated that neurons might exploit quantum effects within biological structures called microtubules, a claim that is still unproven.

But our brains are noisy and warm. Our superconducting chips are cold, clean and quiet. They might be the perfect setting to explore the boundary Penrose described.

Could a classical artificial intelligence wrapped around a quantum core show “mind-like” behaviour? Even if we stop short of consciousness, these systems might reason in new ways, blending unpredictability with logic. They may become powerful reasoning engines, capable of what today’s power-hungry silicon AI are not.

It isn’t science fiction. Many of the parts already exist. Superconducting qubits, which won this year’s Nobel prize in physics, are well developed, and we now have ultra-efficient logic circuits that work with them directly.

But there’s still a long way to go. We will need to solve engineering problems, from memory limits in cold environments to stray particles that can disrupt the system. But these aren’t showstoppers. The deeper challenge is scale. Just as neural nets existed for decades before they appeared in intelligent-acting AI, these hybrid machines may need to grow big before we see what they are really capable of.

If we get there, they might do more than power the next generation of quantum computers. They might help us understand how intelligence works – and what makes a mind.

A collider around the moon

Arttu Rajantie, Imperial College London

Why is the universe overwhelmingly made of matter, and not antimatter? My dream experiment – an underground particle collider encircling the circumference of the moon – could answer this question.

Back in 1789, Antoine Lavoisier formulated the law of conservation of matter, a cornerstone of chemistry that states matter cannot be created or destroyed. Today, in particle physics, this principle still holds. The total number of baryons – protons and neutrons – minus their antimatter counterparts, known as antibaryons, remains unchanged in every reaction we have ever observed.

A particle collider encircling the moon would be an audacious undertaking

Yang Qitian/VCG via Getty Images

There were equal amounts of matter and antimatter in the early universe. This is not the case today, but we have never seen a process that makes more matter than antimatter. The standard model of particle physics predicts it can happen, through an effect known as quantum tunnelling. Quantum tunnelling allows fields to slip between different states that are separated by an energy barrier – a bit like a ball passing through a hill instead of going over it. In quantum field theory, such processes, which are described by objects called instantons, are believed to have been abundant in the hot early universe and would have allowed baryon number to change in reactions. But they are incredibly rare today, so we have never seen them.

My colleague David Ho and I were thinking about how to create the conditions that would give us a chance at glimpsing these instanton processes. We found that a strong magnetic field would speed up these reactions dramatically, but the fields we need are hundreds of times stronger than the LHC can produce. This was when we read about the idea of a collider encircling the moon.

The concept was first put forward by CERN physicists James Beacham and Frank Zimmerman. The pair explained how such a huge feat could be achieved with lunar resources and powered by solar energy using current technology. Ho and I realised that collisions of nuclei of heavy elements – such as lead – in this 11,000-kilometre collider could reach the field strengths we need to see these instanton processes.

Of course, such a massive collider could discover all kinds of new particles or phenomena. But to me, the most remarkable thing is that, with a particle collider around the moon, creating instanton processes, we could destroy matter or create it from pure energy. That would show how the matter we are all made of was created in the early universe and finally break Lavoisier’s two-century-old law.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2501960-inside-the-wild-experiments-physicists-would-do-with-zero-limits/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-12-10 16:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.