Many experts, over many years, have questioned the value of using body mass index (BMI) to determine a patient’s health status. “A person’s health is influenced by a complex mix of health behaviors, genetic factors, lean mass, fitness, and environmental risks,” Holly Ann Russell, MD, author of a recent commentary titled “Is It Time to Say Goodbye to BMI?” said in a statement.

“No simple math formula or number on the scale can measure a person’s health. And using one for that purpose may actually cause harm,” added Russell, a family medicine physician at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York.

Along the same lines, in 2023, the American Medical Association (AMA) summarized the drawbacks of using BMI in a policy statement based on a report stating that ”[n]umerous comorbidities, lifestyle issues, gender, ethnicities, medically significant familial-determined mortality effectors, duration of time one spends in certain BMI categories and the expected accumulation of fat with aging are likely to significantly affect interpretation of BMI data, particularly in regard to morbidity and mortality rates.”

And more than a decade ago, Rexford S. Ahima, MD, and Mitchell A. Lazar, MD, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote in a Science commentary that “the optimal weight that is predictive of health status and morality is likely to be dependent on age, sex, genetics, cardiometabolic fitness, pre-existing diseases, and other factors…BMI does not accurately measure fat content, reflect the proportions of muscle and fat, or account for sex and racial differences in fat content and distribution of intra-abdominal (visceral) and subcutaneous fat.”

And yet, despite the awareness of BMI’s shortcomings, it continues to be used by clinicians around the world to screen for obesity and, in many cases, serves as the foundation for diagnosis and treatment.

What’s behind the ubiquitous use of BMI? And what might be done instead?

Long-Standing Metric

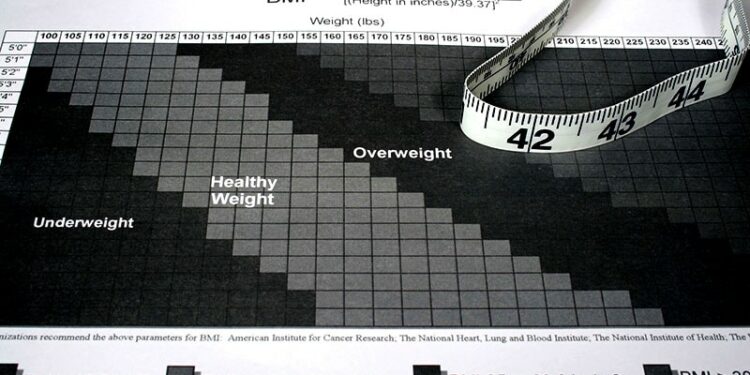

BMI is a calculation of body weight in kilograms divided by the square of a person’s height in meters that has been used for more than two centuries. By many accounts, it dates back to 1832. The tool we use today started with Adolphe Quetelet’s efforts to describe quantifiable characteristics of the “normal man.”

Quetelet was a statistician, mathematician, and astronomer, not a physician, yet the formula he created for nonmedical reasons is the one we use today. The term “body mass index” itself was coined by physiologist Ancel Keys in 1972, and in 1995, the World Health Organization adopted BMI as a measure to define and classify obesity.

Today, BMI categories for adults aged 20 years or older are underweight (less than 18.5); healthy weight (18.5 to less than 25); overweight (25 to less than 30); obesity (30 or greater); and obesity, further subdivided as class 1 (30 to less than 35), class 2 (35 to less than 40), or class 3 (severe — 40 or greater). Notably, BMI categories do not take into account a person’s age, sex, or race.

These omissions led Sabrina Strings, PhD, a Chancellor’s Fellow and an associate professor of sociology at the University of California, Irvine, to write in the AMA Journal of Ethics that BMI “is a continuation of white supremacist embodiment norms, racializing fat phobia under the guise of clinical authority.”

Even if one accepts the current BMI categories at face value, the fact that someone who is fit and healthy — a sumo wrestler, for example — can have a high BMI while someone who is thin and ill can have a low BMI is a primary reason that BMI is a problematic measure for assessing health.

“There are definitely unhealthy people with a low BMI,” Louis J. Aronne, MD, Sanford I. Weill Professor of Metabolic Research at Weill Cornell Medical College and founder and director of its Comprehensive Weight Control Center in New York City, told Medscape Medical News. “Those people tend to have too much body fat even though they’re at a low BMI, meaning that their fat is around their waist in a high-risk depot, and they tend to have low muscle mass.”

“As far as people who have increased body weight and BMI but are healthy, there are not very many of them,” he said. “Often, if you look carefully, you’ll see that they have prediabetes, for example. We doctors don’t screen everyone with obesity for prediabetes, and I can’t tell you how many people come in and we find problems by doing bloodwork.”

Easy, Practical — but Not Enough

Despite its shortcomings, clinicians are reluctant to throw BMI out altogether. “It’s still a very easy, practical and pragmatic way of approaching obesity and weight in a busy clinical practice,” Dimpi Desai, MD, clinical assistant professor in Medicine–Endocrinology, Gerontology, & Metabolism at Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, told Medscape Medical News. “Medical assistants can do it quickly. It’s easy, and inexpensive. It can easily be charted and can help in some way.”

In addition, insurance companies have approved drugs solely on the basis of BMI, she noted. Bariatric surgery is also approved on the basis of BMI. “Therefore, I don’t think that we can not pay attention to it at this point,” she said. “Our biggest goal is to get the medications or the surgery covered, if that’s what our patients need.”

As for characteristics not factored into BMI, history-taking will help, she suggested. This includes asking about race/ethnicity, culture, family history, and medical comorbidities. Furthermore, be aware that the BMI cutoff for obesity is lower in Asian persons and that talks are underway to determine whether cutoffs should also be different for African American persons and Hispanic persons, she said.

The AMA’s policy statement says that using BMI in conjunction with waist circumference “may be a better way to predict weight-related risk” in adults. It also suggests other tests to diagnose obesity and measure health risks, including abdominal circumference data, skinfold measurements, waist-to-hip ratio, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, or hydrostatic weighing/underwater weighing. However, these tools often are not available and may be expensive.

But even without additional testing, it’s possible to include factors that signal or predict health risk, Sriram Machineni, MD, an obesity medicine specialist at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City, told Medscape Medical News. The Edmonton Obesity Staging System (EOSS) is a way of risk-stratifying patients on the basis of comorbidities, functional limitations, and other symptoms. The EOSS uses five different stages to classify risk. Evidence suggests that it is being increasingly used in clinical settings.

“BMI has nothing to do with it, apart from being a qualifier,” Machineni said. “The patient needs to have a BMI above 25 to qualify for the staging system. Then you look at their other comorbidities and talk to them about cardiovascular issues such as heart failure and arrhythmias, or diabetes and prediabetes, and so forth. All of those become additional predictors of the patient’s long-term health.”

Authors of a 2021 pragmatic feasibility study noted that applying the EOSS in routine clinical practice is hampered by the lack of standardized, user-friendly tools that take advantage of data from electronic medical records. They were able to use those data to develop case definitions for the obesity-related comorbidities in the EOSS disease severity stages and to create a clinical dashboard.

“Making this information easily accessible for individual clinical care and practice-level quality improvement may advance obesity care,” they concluded.

In addition, a rapid review of the usefulness of the EOSS in clinical and community settings concluded that the system “should be routinely used for predicting risks and benefits of surgical and nonsurgical weight management.”

‘We Don’t Have the Data Yet’

Despite emerging evidence supporting the use of the EOSS and other ways of determining obesity-related risks, Machineni said, “anyone who says that BMI is no good and should be gotten rid of really shouldn’t be in this field. We have other measures, but until we have a well-defined measure that everyone can easily access, it’s not going to be easy to get rid of BMI completely.”

“Most of the debates have been about how BMI is inaccurate in certain populations,” he added. “That doesn’t invalidate BMI as a measure. As long as you understand the caveats, it can still be used.”

“I’m very enthusiastic about new ways of measuring weight that is higher than normal,” Aronne said. “But it’s going to take time to, in some cases, reanalyze data, and in other cases, develop new studies to show benefit.”

The data are already contained in many studies, he said. For example, his team is in the process of reanalyzing previous studies they’ve done to determine whether replacing BMI with waist-to-height ratio is a better way to measure risk.

“Measuring body composition is something we’re also doing now on a regular basis because of the importance of maintaining lean mass when you’re losing weight, especially in older people. We’re going to see a lot of attention paid to this in coming years. We just don’t have that data yet.”

Overall, he said, “these are things that won’t happen tomorrow, but we’re absolutely looking at better ways to determine risk. Meanwhile, what should the criteria be if it’s not based on BMI?”

Arguably foundational to which measurements are best suited for the clinic will be the upcoming definition of “clinical obesity,” a task undertaken by the Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology Commission on the Definition and Diagnosis of Clinical Obesity.

The commission “aims to identify clinical and biological criteria for the diagnosis of clinical obesity.” As for other chronic diseases, the criteria “should reflect a substantial deviation from the normal functioning of tissues, organs, and the whole organism, with considerable effects on the individual’s ability to conduct daily activities.”

“Ultimately, a clinical definition of obesity coherent with other definitions of disease used in other areas of medicine would provide a crucial tool for the way we conceptualize and treat obesity,” the commission concludes.

Aronne is a consultant to Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly. Machineni is a consultant for Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, and Skye Biotech. He has run clinical trials for multiple pharmaceutical agents, including for Eli Lilly, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Desai declares no conflicts of interest.

Marilynn Larkin, MA, is an award-winning medical writer and editor whose work has appeared in numerous publications, including Medscape Medical News and its sister publication MDedge, The Lancet (where she was a contributing editor), and Reuters Health.

Source link : https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/bmi-good-anything-these-days-yes-least-now-2024a1000pf7?src=rss

Author :

Publish date : 2024-12-31 13:14:54

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.