A clinical trial in Finland will seek to determine whether emergency services can safely use whole blood for transfusions before patients reach the hospital. Other trials held in the United Kingdom and France suggest the return of whole blood is being considered as a replacement product for acute bleeding.

Whole blood products, first pioneered in World War II, are still used in conflict environments from the Ukraine to Palestine and Israel today. But in Europe, whole blood largely disappeared from civilian hospitals in the early 1990s, said Jouni Lauronen, MD, PhD, a pediatric nephrologist by training and principal investigator on the trial at the Finnish Red Cross Blood Service. “Whole blood was used in Finland, like in many other countries, for decades,” he explained.

Finland is validating the use of a whole blood product in a prospective, open study involving two air ambulances and one land unit. The trial will run until the end of 2025. “We are still recruiting, have these three bases using whole blood, and we will compare that with others throughout the country using components,” said Lauronen.

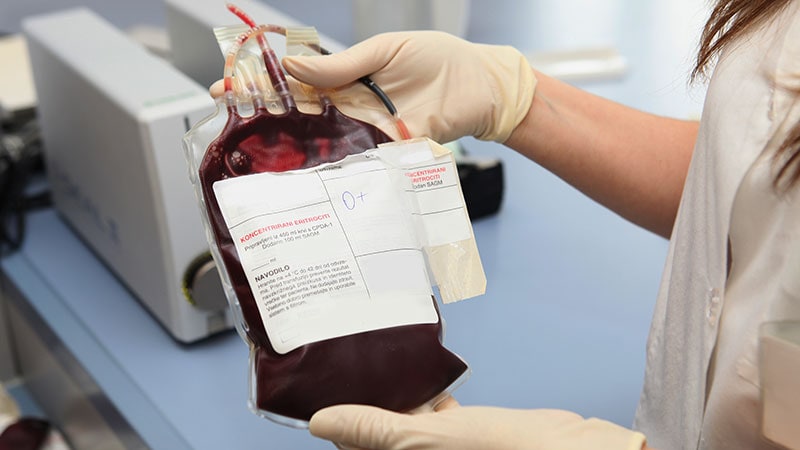

Currently, donated blood is usually divided into components that can be transfused separately: Plasma, red blood cells, and platelets. Individual components were introduced largely because they improved logistics and had longer shelf lives compared with fresh whole blood. Finnish emergency services usually take two components for patients — packed red blood cells and plasma — if there is a likelihood of death from hemorrhagic shock or uncontrolled bleeding.

Reasons for a Return

Components are vital in hospital environments because patients receive exactly what they are lacking, according to Lauronen. “In a hospital setting, you often need only red cells, or only platelets, or only plasma,” he said. “Very often, you don’t need all the components in operating theaters and emergency rooms.”

They are also an efficient use of scarce resources. “We can help three patients with one donation, and that is very ethical,” he added.

However, there are some disadvantages to using components, especially in an air ambulance. First, components have completely different storage requirements: Red blood cells are stored in the fridge, platelets at room temperatures under constant agitation, while plasma is frozen and must be thawed before use.

In the prehospital environment, there is no capacity to run diagnostic tests of coagulation, usually no capacity to hold frozen products, and very limited capacity overall, said Brigadier Michael Reade, DMedSc, DPhil, director of the Greater Brisbane Clinical School and professor of military medicine and surgery at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. “Therefore, it is theoretically better to replace all the elements of blood that are being shed as whole blood [in a major hemorrhage patient], than to guess what specific components they require, some of which, such as plasma and platelets, will not be available,” he said.

It is, of course, possible to provide blood transfusions with three individual components in a balanced ratio, but this can be quite difficult logistically in an air ambulance, added Professor Torunn Oveland Apelseth, MD, PhD, director of the Norwegian Centre for Blood Preparedness (Nokblod) at Bergen Hospital Trust, Bergen, Norway, and senior consultant at the Department of Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway. Several access points are required, and emergency staff must decide which bag of component to administer first. “It is easier to transfuse one unit containing all elements of the blood you need,” she explained.

That is especially true because, during processing, anticoagulants and additive solutions are added to all blood products to improve quality during storage. This means that, in Norway for example, seven bags of individual components would have to be administered for every three bags of whole blood.

“A whole-blood-based resuscitation strategy gives you a more concentrated transfusion,” she said. “So if you use whole blood, you give more of what the patient needs and less excess fluid.”

These factors led Bergen Hospital Trust to introduce whole blood to its air ambulance service back in 2015.

Whole blood has its disadvantages too, said Lauronen. For example, if O-positive whole blood is given without testing for anti-A and anti-B antibodies, there is a risk of hemolysis.

Broader European Interest

Trials to establish the benefits of whole blood compared with components have been patchy — often small, observational, or inconclusive.

That is why the United Kingdom launched a multicenter randomized controlled prehospital trial. Study of Whole Blood in Frontline Trauma is comparing the use of up to two units of whole blood with standard care (red blood cell + plasma, but no platelets) in 10 air ambulance services.

And while the United Kingdom and Finland are pressing on with trials looking solely at prehospital use, France’s Trauma-Sang Total dans les Hémorragies Massives trial is a hospital trial.

All trials, interestingly, have links to the military.

Terrorist attacks in Paris prompted the French trial. “War type casualties were clearly occurring in civilian settings in France,” said the trialists in their published trial protocol. Providing blood has been a real challenge to teams in charge of patients, particularly during the attack in 2015. “It revealed significant delays despite the knowledge that every second counts.”

Like France and the United Kingdom, the military is very much part of the blood preparedness strategy in Norway. But Norway has gone further, implementing whole blood throughout its hospitals, and not just in trauma wards, since 2017. The main patient groups receiving whole blood are trauma and surgery patients, in addition to those with obstetric and gastrointestinal bleeds, according to Apelseth.

Whole blood is used for postpartum bleeds, for example, which can be severe. When first introduced at Haukeland University Hospital, red cells were stored at the obstetric ward. “But during these years, the obstetricians have changed their practice and now demand to have whole blood stored in the obstetric ward instead of red cells,” she explained.

Apelseth said every patient who receives blood enters a national registry that is monitored for safety and quality purposes. “Several laboratory studies have been done, but we did not do a randomized clinical study before implementation,” she said. “But at this point, no one, neither clinicians nor blood bank staff, wants to turn back.”

Whole blood trials are notoriously difficult to carry out. Reade points out that the Finnish study is not randomized, so there could be confounding factors. And prehospital trials are more likely to determine a value to whole blood. “Because that is where the greatest preventable mortality lies,” he said. “A clinical trial in hospital is less likely to see a benefit of a novel intervention.”

Should these countries conclude whole blood is feasible, other issues will have to be considered, such as cost and waste, especially if blood collected is not used. “If we are collecting a lot of whole blood for prehospital settings and not using it, then we won’t have enough donors,” said Lauronen, concerned that people would not want to donate again.

Reade, Lauronen, and Apelseth have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Tatum Anderson is a global health and medical journalist. For over 20 years, she has placed articles in publications from the Bulletin of the World Health Organization to The Lancet, BMJ, BBC News, and The Economist.

Source link : https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/whole-blood-making-comeback-civilian-practice-2024a1000osn?src=rss

Author :

Publish date : 2024-12-20 13:37:51

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.