[ad_1]

PA Media

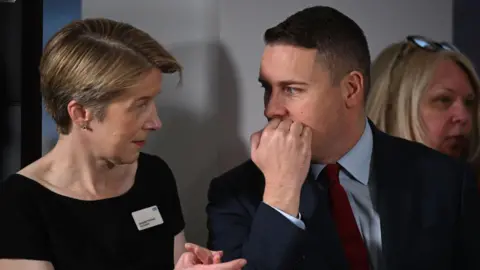

PA MediaAmanda Pritchard, head of NHS England, would have regular Monday meetings with Health Secretary Wes Streeting to review performance and address challenges. But last Monday was different. After discussing the state of the health service, she announced she was stepping down – with just one month’s notice.

It came as a shock to many in the organisation, under which there are 1.4 million staff who deal with 1.7 million patients everyday. But those in the know had suspected something was happening – though not the timing.

That meeting between Pritchard and Streeting was the natural conclusion of changes which had been rumbling on in the corridors of power for some time.

NHS England was given autonomy by the then-Conservative Health Secretary Andrew Lansley in 2013. The aim was to free the organisation from interference by politicians.

Under Sir Simon Stevens – now Lord Stevens – NHS England developed into what looked like a rival power base and led by an alternative health secretary. He was at the heart of work drawing up long-term NHS plans under David Cameron and Theresa May. Lord Stevens knew his way around Whitehall and knew how to win backroom battles with ministers.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAmanda Pritchard had been deputy to Lord Stevens since 2019 and played a vital role in the NHS response to the pandemic, including the vaccine roll-out. It had seemed inevitable she would take over the top job in 2021. Understandably, she expected to continue in the same vein as her predecessor. But with the arrival of a Labour government last year that certainty began to weaken.

The first clue that things would be going back to a more traditional management regime, with more direct government control, came when two health experts were appointed from previous Labour governments: Alan Milburn, Blair’s health secretary, and Paul Corrigan, an adviser. It became clear that they would be involved in shaping policy with Wes Streeting.

One well-placed health source said those two “remembered the old days”, before the NHS’s shift to autonomy, which they felt made the system “too bureaucratic”.

Another clue came when work began on a new NHS 10-year plan for England. With previous plans Lord Stevens had “held the pen”, but this time the government brought in Sally Warren from the King’s Fund think tank – outside NHS England management – to head up the the work.

At the same time, noises were being made about slimming down NHS England management – and instead devolving money to local health boards and patient services. Government sources deny that NHS England is being subsumed into the health department but say it will have a “leaner” role, cutting out duplication.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAmanda Pritchard was well aware of the direction of travel. She could see that her job was going to change and had considered stepping down later this year. There has been no suggestion of any row or confrontation with Wes Streeting.

NHS officials say that the decision to leave at the end of March was because it will be the end of a financial year – and there was no need to stay for the launch of the 10-year plan in the early summer.

In January Ms Pritchard had a bruising experience at the hands of two parliamentary select committees. One suggested she and colleagues were “complacent” and another said they were disappointed with “lengthy and diffuse answers”. In a BBC interview she admitted that “we’re not all brilliant performers at committee hearings” but it was right to be scrutinised. Privately, according to sources, she found the process “frustrating given how much time she had given to the role” under some of the most difficult years in the history of the NHS.

She will be replaced by Sir Jim Mackey, an experienced NHS trust boss, who is being titled the “transition” chief executive. Policy will be run by Wes Streeting’s department with Sir Jim, we are told, focusing on delivery including cutting the hospital waiting list of nearly 7.5 million. He had recently helped draft a recovery plan for planned treatment and appointments.

So where does all this leave the NHS?

On one hand, Amanda Pritchard has provided consistent leadership in various roles under six different health secretaries. The autonomy of NHS England enabled its chief executive to bang the drum for the health service and pressure the government.

But on the other hand, serious problems remain with patient outcomes and those closer to Streeting argue more direct government control means less bureaucracy, and the ability to free up resources to deploy where needed.

One health source argued that the upcoming changes would end confusion over policy and strategy and encourage collaboration between ministers and NHS England – without being a formal takeover. But another suggested it was “a bit of a mess” and there could now be instability and distractions for NHS administrators when they need to focus on wider health challenges.

Much will depend on how much money is allocated in the Treasury spending review.

It’s patients that matter – and it’s not yet clear whether or not these changes will help them.

[ad_2]

Source link : https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c8rkgvydrr3o

Author :

Publish date : 2025-03-02 01:12:11

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.