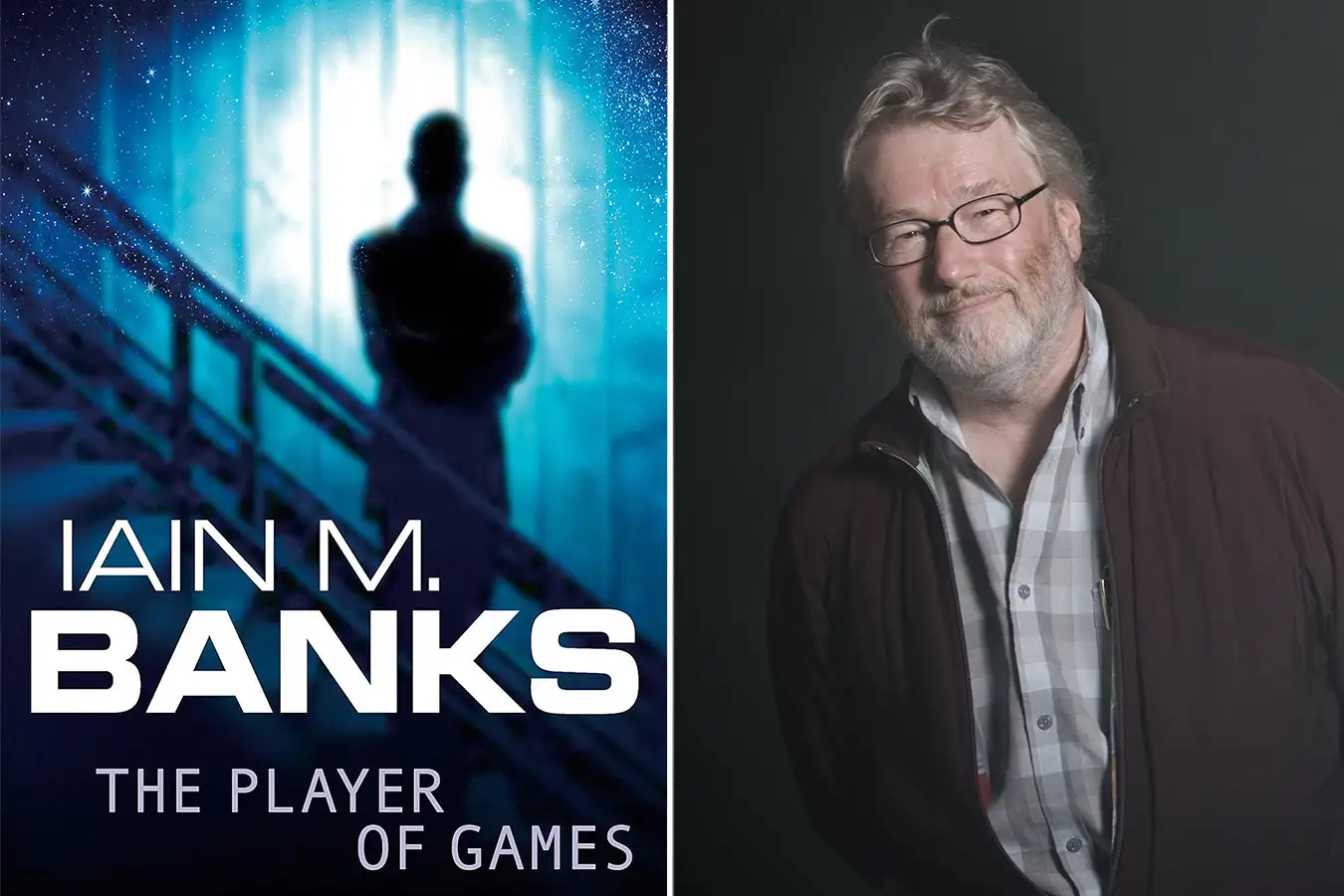

The Book Club has been reading Iain M. Banks’s The Player of Games

Colin McPherson/Corbis via Getty Images

The New Scientist Book Club moved from the dystopian near-future imagined by Grace Chan in Every Version of You in November to the utopian far-future imagined by Iain M. Banks in The Player of Games for our December read – and it’s been quite the hit with members.

Set in the intergalactic civilisation of the Culture, The Player of Games follows the adventures and travails of Gurgeh, a master game player who is inveigled into taking on the barbaric Empire of Azad at its own game. Also known as Azad, this complex and all-pervasive game is so important to the people of Azad that the winner becomes emperor. Can Gurgeh possibly compete, when he’s only a beginner? What are the secrets that Azad and the Culture are hiding? This is a wrap-up of members’ thoughts on the book, so the answers to these questions, and multiple spoilers, will follow. Read on only if you’re done!

The first thing to say is that this wasn’t a first read for many of us: 36 per cent of members, including me, said they’d already read this particular Banks novel. And lots of us are big fans of Banks, and are still mourning the fact that there are no new novels – sci-fi or literary – to come from this wonderful writer. “Oh, I still miss Iain. I’ve never read his last book, The Quarry, as after that there will be no new ones to read. I guess it’s about time now, I’m getting to the age where I might never read it!” writes Paul Oldroyd on our Facebook group. “Same here – I’ve never finished The Hydrogen Sonata!” adds Emma Weisblatt.

I think I’ve read most of Banks’s books, although not for years. The Player of Games was one of my first, so, given my terrible memory, I came to it fairly fresh. I found it an absolute delight – I’m sure there is lots going on behind the scenes, but Banks gives the air of effortless brilliance to the reader. His touch is so light, so naturally funny. (I adored, for example, the small detail of the “proto-sentient Styglian enumerator”, an animal that counts everything it sees. It starts by counting people, of which there are 23. “Then it began counting articles of furniture, after which it concentrated on legs.”)

But there is also so much to think about, from the nature of life in a utopia where there are no challenges left, to what it means to be a human in a universe where vast Minds take charge of everything. And that’s not to mention the joys of the plot – I was almost shouting at the page when Gurgeh was tempted into cheating at the game of Stricken by Mawhrin-Skel, and I was utterly swept up in the Azad games. This was a real win for me, and I’m going to go back and reread lots of other Iain M. Banks as a post-Christmas treat.

One aspect of the book that I thought Banks handled particularly well was the actual games Gurgeh plays. It’s not easy to invent a futuristic game and have it ring true, and I felt he nailed this, giving us enough details about Azad (and other games) for them to seem real, but not getting bogged down in the nitty-gritty. This was definitely an aspect that also interested members. “The game [Azad] was a representation, an encapsulation if you will, of the empire,” says Elaine Li. “More generally it was probably a critique of Cold War politics.”

Judith Lazell wasn’t so sure – “I just took them at face value, I’m afraid,” she says. Niall Leighton points out quite how deep this idea of game-playing goes in the book. “And then, not least, is the game in which Gurgeh is a pawn being played by the narrator, in a game with no rules, in which ends justify the means, whose rounds last decades, whose moves we are left to guess at just as much as we are in the other games, and in which there may indeed be no ends.” Indeed!

A small aside: when I spoke to Banks’s friend and fellow sci-fi writer Ken MacLeod, Ken told me proudly that it was actually him who came up with the book’s final title. Banks had wanted to call it The Game Player. I think The Player of Games is much better!

Now, to what we thought of Gurgeh as a character. “Gurgeh would not be a very nice person if he had not been bought up in the culture – he’s a bit of a creep, a bit self-obsessed. I hope he learned something from his adventures,” says Matthew Campbell by email. I’m not sure we’re meant to like him, particularly – he’s a disaffected, arrogant cheat, after all – but I definitely found myself rooting for him as the story progressed.

Steve Swan, however, wasn’t as grabbed by the narrative. He put the book aside “at the point [Gurgeh] was being roughed up” – I’m assuming this was when Mawhrin-Skel meets him on his way home. “Clever people, especially those who think they are, can make the biggest mistakes,” says Steve. “Gurgeh should have seen past the [drone’s] ruse, but his arrogance and personal desires got in the way. What’s that old saying? – he made his bed and had to lay in it. No sympathy from me I am afraid!” Steve felt that Gurgeh fell for Mawhrin-Skel’s manipulation too easily, and it “caused the disbelief I had set aside to crumble”.

Niall has a different take on why Gurgeh makes his fateful decision to cheat. “The way I read this passage was that his mind was being tampered with by Mawhrin-Skel using its effectors. It wasn’t his free will. It was the drone influencing him to the point where he could think he’d made the decision himself,” says Niall. “He’s manipulated by Special Circumstances from start to finish. To me, Gurgeh is not the titular player. He’s being played.” While I think that’s definitely true overall, I saw Gurgeh’s cheating as a very human response to temptation, rather than another manipulation… but I’m going to have to check out this section again, as it’s an interesting supposition.

While Paul Jonas didn’t find Gurgeh the game player “as engaging as the mercenary role in Consider Phlebas or Use of Weapons”, he did think the set-up with the drone was “fairly credible and tempting for a top ‘sportsman’”. “It’s all part of the hero avoiding the call to adventure for a while. After all, why would Gurgeh throw up all his security and comfort without a little nudge?”

Our sci-fi columnist Emily H. Wilson had tipped The Player of Games as a good way into the work of Iain M. Banks, and after this reread I definitely agree. We’re gradually introduced to the universe of the Culture, not with a huge dump of exposition, but with small details about drones and Ships and Orbitals and the like.

We get to slowly understand that this is a post-scarcity civilisation where (almost) anything goes. I loved Gurgeh’s conversation with Hamin, an Azadian elder, on this topic. Hamin can’t understand why there is almost no crime, and almost nothing is forbidden, in the Culture – and he’s told about slap-drones, which are employed in the event of a murder. What does it do? “Follows you around and makes sure you never do it again,” says Gurgeh. Is that all, asks Hamin? “What more do you want? Social death, Hamin; you don’t get invited to too many parties.”

Paul Jonas already had an idea of the utopian worlds of the Culture when he picked up The Player of Games. “[It] builds that world again very subtly by following Gurgeh and his boredom and lack of challenge. Anyone who wants a house like his on a rainy mountain can have one. The drones are introduced just as personalities and Ai’s in their own right. We are re introduced to ‘Contact’, the Culture’s service that manages contact with other civilisations and is also its military and intelligence service,” says Paul. “That’s so great to call it ‘Contact’ rather than ministry for defence or war! So humanitarian. So utopian. But as Adam Roberts says, utopias are difficult to write as they become boring, just as Gurgeh has become bored by his life. The Culture’s challenge is to spread their utopianism to other cultures by essentially subtly interfering in their societies.”

Some of our members have been digging into what it might mean to live in a utopia. “Gurgeh is an individualist living in a utopia of individualists where the collective work is mostly done by Minds and drones and sentient spaceships,” ponders Paul. “Gurgeh never seems to work in a team of other humans.”

Niall points out that Gurgeh might be “odious”, but he is a product of his anarchist society, and Banks is out to examine “the boundary between individualist anarchism and collectivist anarchism”.

“Gurgeh’s clearly an individualist, and I reject individualist anarchist philosophies in part because they’re an excuse for behaving like Gurgeh,” says Niall. “One of the Culture’s problems is that there’s nothing to engage its human people. It’s also static, which doesn’t help, and the consequence is a predictable ennui. It’s perhaps worth flagging up that this book was written before Octavia Butler placed the importance of change in a utopia at the forefront of her thinking, but it’s been thought about at least since H. G. Wells.”

For Matthew Campbell, it is only the Culture ambassador to Azad, Shohobohaum Za, who seems “to be really vitally alive and enjoying life”. “In contrast, Gurgeh and the Azadians are each stuck in their own small worlds, each in their own way,” he says. “The confrontation between [Azadian emperor] Nicosar and Gurgeh towards the end sums it up (and presciently echoes political debates today – sorry not sorry if you are a MAGA conservative) – one angrily passionate about his empire but seeing it only from a very narrow selfish perspective, and knowing that it is all doomed; the other having no strongly articulated beliefs at all, unable to muster a defence of his utopia, he’s never had to think about it.”

There’s a lot more we could all say about the Culture and The Player of Games, and if you want to continue the discussion, do join members over on Facebook.

It’s time, meanwhile, to move onto our first read of 2026: January’s book club pick and winner of the Arthur C. Clarke award for science fiction in 2025, Sierra Greer’s Annie Bot. This is told from the perspective of Annie, who is a sex robot. She is owned by a not-very-nice man, and this novel does go to some dark places. But as chair of judges for the Clarke award, Andrew Butler, said when announcing its win, it’s “a tightly-focused first person account of a robot designed to be the perfect companion who struggles to become free”. You can try a taster with an extract from the opening here and a piece by Sierra Greer on what it was like to write from the perspective of a sex robot here. And here’s Emily H. Wilson’s review – she really liked it.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2509053-our-verdict-on-the-player-of-games-iain-m-banks-is-still-a-master/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2026-01-02 08:55:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.