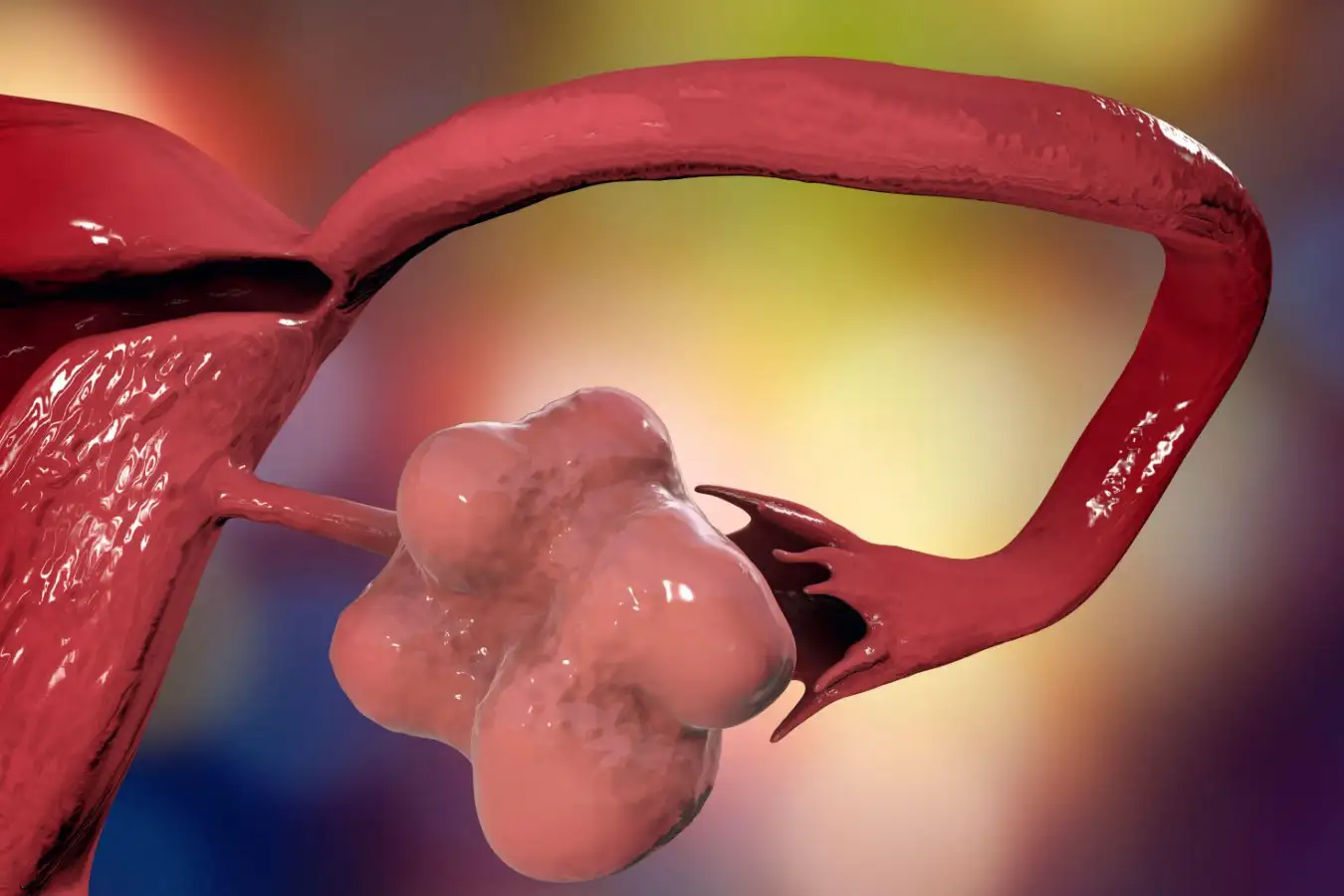

An illustration of polycystic ovary syndrome, which causes the ovaries to enlarge

Science Photo Library / Alamy

We are finally getting to grips with the genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which could open the door to new treatments.

PCOS, which is thought to affect up to 1 in 5 women, disrupts how ovaries function, resulting in at least two of three features: irregular or no periods; raised levels of male sex hormones, including testosterone; and a build-up of immature eggs that look like cysts in the ovaries. As a result, fertility problems are common with the condition.

Its exact cause is unknown, but PCOS has been linked to changes to the gut microbiome and hormonal imbalances before birth. It also runs in families, with studies estimating that about 70 per cent of an individual’s risk is down to genetics. But so far, researchers had identified only about 25 genetic variants – involved in the production of sex hormones, like oestrogen and testosterone, and ovarian function – that explain about 10 per cent of a person’s risk.

To fill this knowledge gap, Shigang Zhao at Shandong University in Jinan, China, and his colleagues analysed the genomes of more than 440,000 women across China and Europe, 25,000 of whom had been diagnosed with PCOS, while the remainder hadn’t, in the largest genetic analysis of the condition to date.

The team pinpointed 94 genetic variants that seem to influence PCOS risk, 73 of which had not previously been identified. One of the most interesting of these variants occurs in the gene encoding for mitochondrial ribosomal protein S22, which helps mitochondria, the energy-generating parts of cells, to function properly, says Zhao. While prior studies have linked PCOS to dysfunctional mitochondria, this is the first look at how genetics may underly this, he says.

Another newly identified variant affects a protein called sex hormone-binding globulin, which regulates the activity of sex hormones, and is commonly found at low levels in people with PCOS.

Many of the remaining variants influence the function of the ovary’s granulosa cells – which produce oestrogen and progesterone, and help eggs develop – across the menstrual cycle. This supports the idea that genetics drive PCOS by altering levels of sex hormones, says Zhao.

Overall, the team calculated that the 94 variants explained about 27 per cent of the variation in PCOS risk among the European participants and about 34 per cent of the risk among the Chinese populations.

“This study is important because it’s expanding our understanding of the genetic component of the disease,” says Elisabet Stener-Victorin at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. It also highlights the need to include diverse ancestries in genetic studies of PCOS, says Zhao.

In a final analysis, the researchers pinpointed drugs that could correct the pathways affected by the variants they identified. Some of these are already used to treat PCOS, such as clomifene, which stimulates the release of eggs from the ovary, a process disrupted by the condition. The team also found that betaine – sometimes used to treat the genetic condition homocystinuria, which can cause eye and skeletal problems – could also benefit those with PCOS. Studies in mice with induced PCOS-like symptoms could explore this as a treatment option, says Zhao.

“Today treatment is symptom-orientated; there is no drug that can cure PCOS,” says Stener-Victorin. Common therapies include the contraceptive pill to regulate periods, clomifene or the type 2 diabetes drug metformin, which can enhance fertility. But no one treatment is effective for everyone. “Identifying clusters of genes that influence PCOS risk can really help us to direct and do more targeted treatment for these women,” she says.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2502830-were-closing-in-on-how-genetics-may-influence-your-pcos-risk/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-11-04 17:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.