Primary care physicians (PCPs) often face challenges in diagnosing complex pulmonary issues in patients, particularly when nonspecific symptoms appear similar to cardiovascular issues, asthma, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

However, clinicians can cover both pulmonary and cardiovascular concerns during an exam, potentially shortening delays in the diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases (ILDs), including pulmonary fibrosis (PF).

“ILDs are complex, chronic progressive diseases with a great impact on a patient’s quality of life and survival. These are often underdiagnosed, or there is significant delay in diagnosis after onset of symptoms due to a multitude of reasons,” said Tejaswini Kulkarni, MD, associate professor of pulmonary, allergy, and critical care medicine and director of the interstitial lung disease program at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Alabama.

“Early intervention can slow disease progression, improve quality of life, and potentially extend survival in ILD patients,” she said. “For primary care physicians, increased awareness of the signs and symptoms of ILD and early recognition are crucial.”

Timely Diagnosis Tools

Although most PCPs try to evaluate the root causes of nonspecific symptoms, about 2 in 5 tend to bypass symptom evaluation if the patient is already on inhaled therapy for a pulmonary condition, according to a survey by the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST). Instead, they often modulate therapy — for what may be an incorrect diagnosis.

“As a practicing primary care physician, it doesn’t surprise me that PF and ILD are generally misdiagnosed or experience delays in diagnosis. These diseases are on the rare side, so when a patient comes to their PCP, that doctor first will opt to rule out heart issues that can quickly end a life,” said William Lago, MD, a family medicine physician with the Cleveland Clinic-Wooster Family Health Center in Wooster, Ohio.

“That said, lung diseases like PF are incredibly difficult to live with and can progress rapidly if untreated,” he said. “An earlier diagnosis means starting treatments to slow fibrosing of the lungs, and with slowed disease progression, a patient’s quality of life is often improved.”

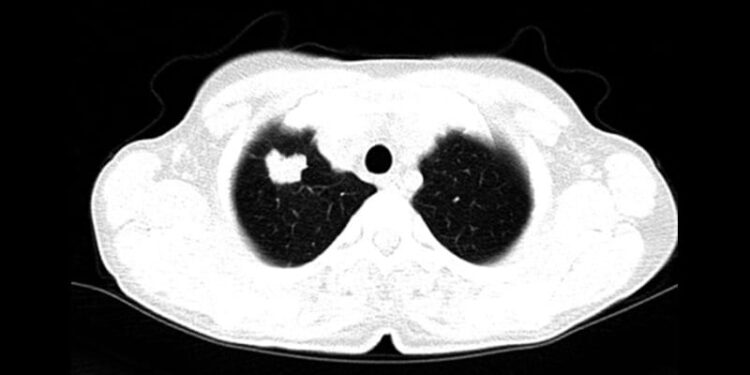

In general, high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) is considered the gold standard for imaging when it comes to detecting ILD. However, only 62% of PCPs said they order HRCT when a patient’s chest radiograph shows lower lobe opacity, and only half said they order it when a patient has inspiratory crackles or other abnormalities during a pulmonary exam, according to the CHEST survey.

In response, CHEST and the Three Lakes Foundation sponsored a clinician toolkit, which was created by PCPs and pulmonologists to help clinicians better identify, manage, and treat ILDs. The toolkit includes a patient questionnaire, a decision-making module with patient case studies, an online module with in-depth ILD symptoms and sounds of crackles, and videos of radiologic features of ILDs. The project, called Bridging Specialties: Timely Diagnosis for ILD, also includes white papers and podcast episodes on overcoming barriers to diagnosis.

“In working on this initiative with my pulmonary colleagues, I’m already finding myself thinking more about PF and ILDs as potential diagnoses when seeing patients,” said Lago, who served on the Bridging Specialties expert steering committee. “Between the patient questionnaire, the decision-making module, and the other resources in the clinician toolkit, I can see this having an incredible impact on how we diagnose patients.”

This teamwork approach can help PCPs improve diagnosis rates alongside other specialists, said Kulkarni, who also served on the Bridging Specialties committee.

“Many patients present with vague or nonspecific symptoms, and ILDs can mimic other, more common respiratory disorders or coronary artery diseases, along with shared features of older age and history of smoking,” she said. “The differential diagnosis is complex and often requires a multidisciplinary team of pulmonologists, rheumatologists, radiologists, and pathologists to identify the subtype of ILD.”

Other medical societies have created informational resources as well, including the American Thoracic Society’s ILD and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) resources and the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation’s webinars and clinical resources.

“My top advice is to go to reputable sources. I’ve had one patient ask me about drinking hydrogen peroxide to treat their condition, which they read on a forum online. Others have asked about stem cell therapy in other countries, which isn’t regulated and can do real harm,” said Jeffrey Horowitz, MD, professor of medicine and division director of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine at Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

“Overall, I tell clinicians that if somebody is short of breath, has crackles, and has a normal echocardiogram, it’s probably not the heart, so do those pulmonary function studies early,” he said. “Since most nonpulmonologists don’t have substantial expertise in this area, it’s a good idea to have patients evaluated at an academic medical center with expertise in ILD, which also opens the doors for patients to be enrolled in clinical trials.”

Ongoing Research and Treatments

Ohio State, for instance, recently joined the IPF-PRO/ILD-PRO Registry, an industry-academic collaborative started by Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, in 2014 to maintain a registry of patients for potential therapies and clinical trials.

“There can be a sense of nihilism regarding this entire spectrum of fibrotic lung disease, which wouldn’t be without merit if we were talking about 20 years ago,” Horowitz said. “Today, there are a lot of reasons to be optimistic as we’re making gains and improving care for these patients.”

Numerous clinical trials are underway, including positive phase 3 results for FIBRONEER-IPF from Boehringer Ingelheim. The trial found that nerandomilast, an oral form of a phosphodiesterase 4B inhibitor, improved forced vital capacity (FVC) at 52 weeks, as compared with placebo. The drug hasn’t yet been approved for use, but full efficacy and safety data are expected sometime in 2025.

In addition, United Therapeutics offers inhaled forms of treprostinil, which was initially approved to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension, as well as pulmonary hypertension associated with ILD. New data indicate the medication could also benefit patients with IPF who don’t have pulmonary hypertension, Horowitz said. The ongoing trial is enrolling patients across the United States.

Other ongoing studies include lysophosphatidic acid, a bioactive lipid mediator that can affect lung inflammation and fibrosis, and bexotegrast, a dual selective inhibitor of αvß6 and αvß1 integrins developed to treat IPF. Although Pliant Therapeutics announced the discontinuation of a phase 2b trial in March, early data showed efficacy for improved FVC.

“I’m optimistic that the next breakthrough is just around the corner,” Horowitz said. “After 15 years of doing high-quality, informative studies, we’re now opening the doors for new therapeutic targets, and as long as we keep doing trials, we’re going to make a breakthrough that’s going to transform care for these patients.”

Horowitz and colleagues are also studying the cellular matrix and cell death of fibroblasts, including the way lung cells interact with other cells in an aberrant wound repair response, ultimately leading to lung scarring. The latest research is focused on enhancing cell susceptibility to apoptosis, or cell death, and decreasing disease progression.

“These lung diseases are heterogeneous, just like cancer. So viewed through the lens of cancer biology, different patients with their own fibrotic diseases have underlying mechanisms that drive the disease process,” Horowitz said. “We’re pursuing the idea that, if we can target the metabolic pathways that cells use, it might be beneficial for developing therapeutics.”

Additional developments are occurring in diagnosis and patient care as well, particularly with a focus on genetic testing and coordinated care across specialists.

“The landscape of ILD treatment is evolving with the introduction of new pharmacological agents, advanced diagnostic techniques, and improved interdisciplinary care models and offers a brighter outlook for patients and healthcare providers,” Kulkarni said. “Looking ahead to 2025 and beyond, as our understanding of disease pathogenesis continues to grow, the integration of precision medicine and genetic insights has the potential to make patient-centered, individualized care a reality.”

Kulkarni, Lago, and Horowitz reported receiving grants, consulting fees, and serving in advisory roles for numerous pharmaceutical and medical organizations.

Carolyn Crist is a health and medical journalist who reports on the latest studies for Medscape, MDedge, and WebMD.

Source link : https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/primary-care-physicians-can-close-gaps-delays-diagnosis-2025a1000d7p?src=rss

Author :

Publish date : 2025-05-26 11:43:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.