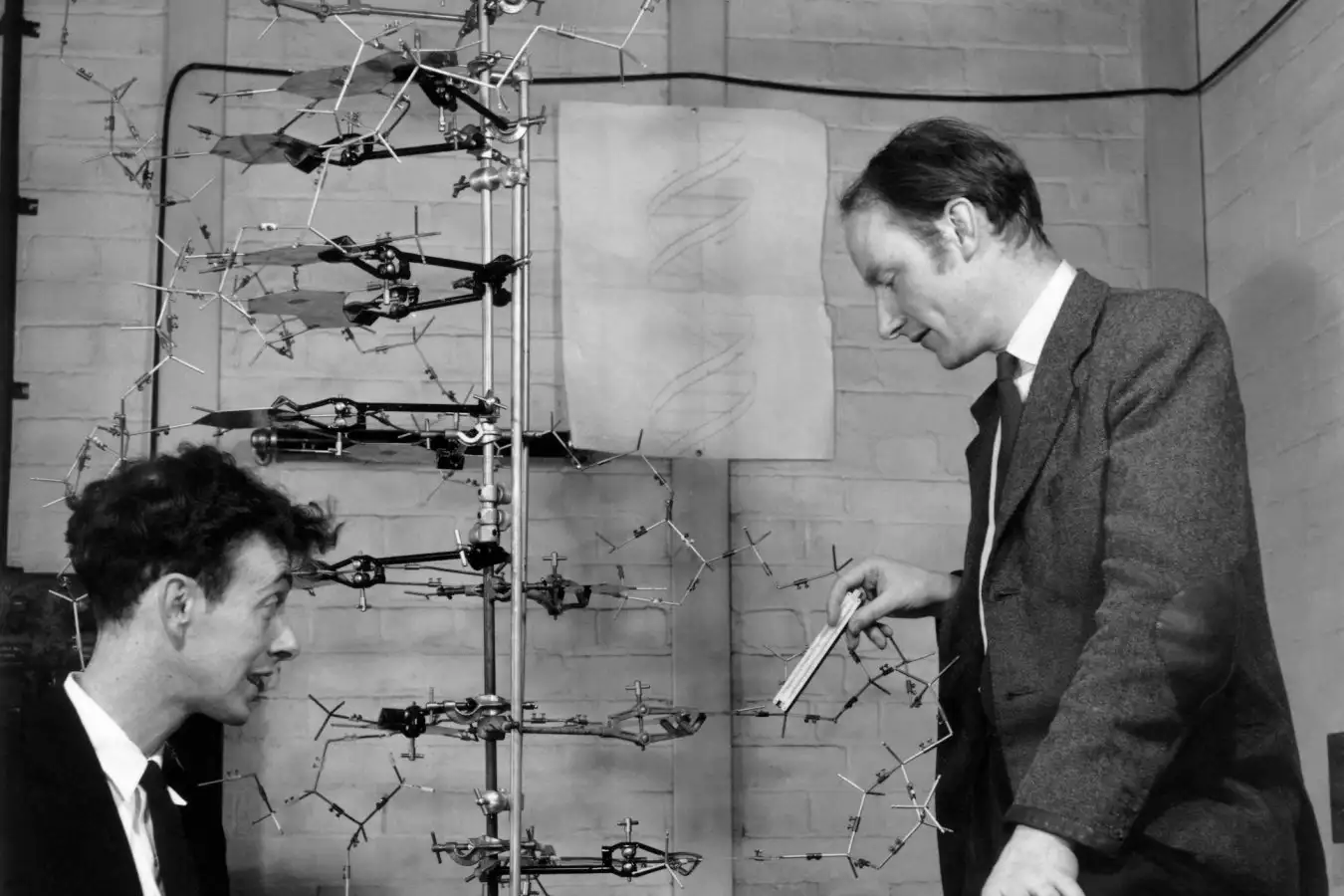

Francis Crick (right) and James Watson in 1953 as they modelled DNA

A. BARRINGTON BROWN, GONVILLE & CAIUS COLLEGE/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Crick: A mind in motion – from DNA to the brain

Matthew Cobb, Profile Books, UK; Basic Books, US

Francis Crick missed a crucial seminar in 1951, probably because he was seeing a lover. James Watson did go, failed to take notes and misremembered key details. As a result, their first model of DNA was embarrassingly bad.

This is one of many fascinating details in Crick: A mind in motion – from DNA to the brain, a biography by zoologist and writer Matthew Cobb. If you are interested in how DNA’s structure was discovered and what happened next, this is the book to read.

A son of shopkeepers, Crick didn’t do well enough at school to get into Oxbridge, got a second-class degree and was doing a very dull PhD on water’s viscosity until he was sent to work on sea mines during the second world war. By 1947, he was a civil servant with a failed marriage and his son was living with his grandparents. But Crick’s reading had left him fascinated by the molecular underpinnings of life and of consciousness. He went back into research, initially working at an independent lab in Cambridge, UK.

In 1949, he began studying the structure of biological molecules by looking at how they diffract X-rays. His notebooks catalogue his blunders: spillages, misloaded films, wrongly placed samples and more. Crick twice flooded the corridor outside his boss’s office, and annoyed his colleagues by talking endlessly to Watson. The pair were banished to a remote room.

By 1952, Crick had a new family, but was broke and at risk of being sacked by his boss, Lawrence Bragg. Then Bragg’s rival, biochemist Linus Pauling, claimed he had worked out DNA’s structure. He was wrong, but Bragg didn’t want Pauling to get there first, so he gave Crick and Watson the go-ahead to work on DNA. By March 1953, they had solved it.

“

Crick succeeded in part because he was willing to fail, proposing many ideas that turned out to be wrong

“

Yes, chemist Rosalind Franklin’s data was vital – but Crick and Watson didn’t steal it, writes Cobb. He has also found papers suggesting Crick, Watson, Franklin and her colleague Maurice Wilkins were all more collaborative than anyone knew.

Many forget that Crick and Watson cited Franklin and Wilkins in their famous Nature paper and that papers by Franklin and Wilkins appeared alongside it. Franklin also became a friend of Crick and Odile, his second wife, often staying with them while recovering from operations for the cancer that killed her. This early death is why she didn’t share their 1962 Nobel prize.

Crick went on to play a major part in uncovering how DNA coded for proteins, having many important insights about the process. The biography is a gripping read up to this point, but here it fades a bit, reflecting Crick’s life rather than Cobb’s writing. After the genetic code was cracked in the 1960s, Crick published a series of bad papers, and in 1971 he experienced what was probably depression.

He moved to California in 1977, shifting his attention to consciousness. Cobb argues that his contributions there were as important as his work in molecular biology, in that he proposed or popularised approaches that are now mainstream, such as figuring out the brain’s “connectome”.

This book is also about Crick the man, and he was a curious mix. Anti-religious and anti-monarchy, the book details how he had an open second marriage, supported the legalisation of cannabis, took acid and held wild parties at which pornography was sometimes screened. It also notes that he made unwanted sexual advances to several women.

What’s more, he corresponded with racists about IQ and genetics, then came to believe this issue was more complex than he first assumed, writes Cobb. Crick never mentioned it after the 1970s – in stark contrast to Watson, who died last week at the age of 97.

It is clear Crick succeeded in part because he was willing to fail, proposing and publishing many ideas that turned out to be wrong. That said, he was also brilliant. One Saturday morning, for instance, he read a paper outlining the X-ray results for a protein. By noon, he had solved its structure, with help from a visiting friend.

As I read, it struck me that Crick probably lacked the credentials to make it as a scientist now. Researchers today will be astounded to discover that he did no formal teaching and only ever wrote one grant application. There may never be any more Cricks, because we have created a system that doesn’t nurture his kind of genius.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg26835692-000-surprising-new-biography-of-francis-crick-unravels-the-story-of-dna/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-11-12 18:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.