It is fair to say that the family tree of ancient humans is not written in stone. Just take the case of the Denisovans, the enigmatic ancient humans who were, until recently, known only from a few fragments of bone. In June, molecular evidence indicated that a mystery skull from China was actually a Denisovan. These ancient people suddenly had a face.

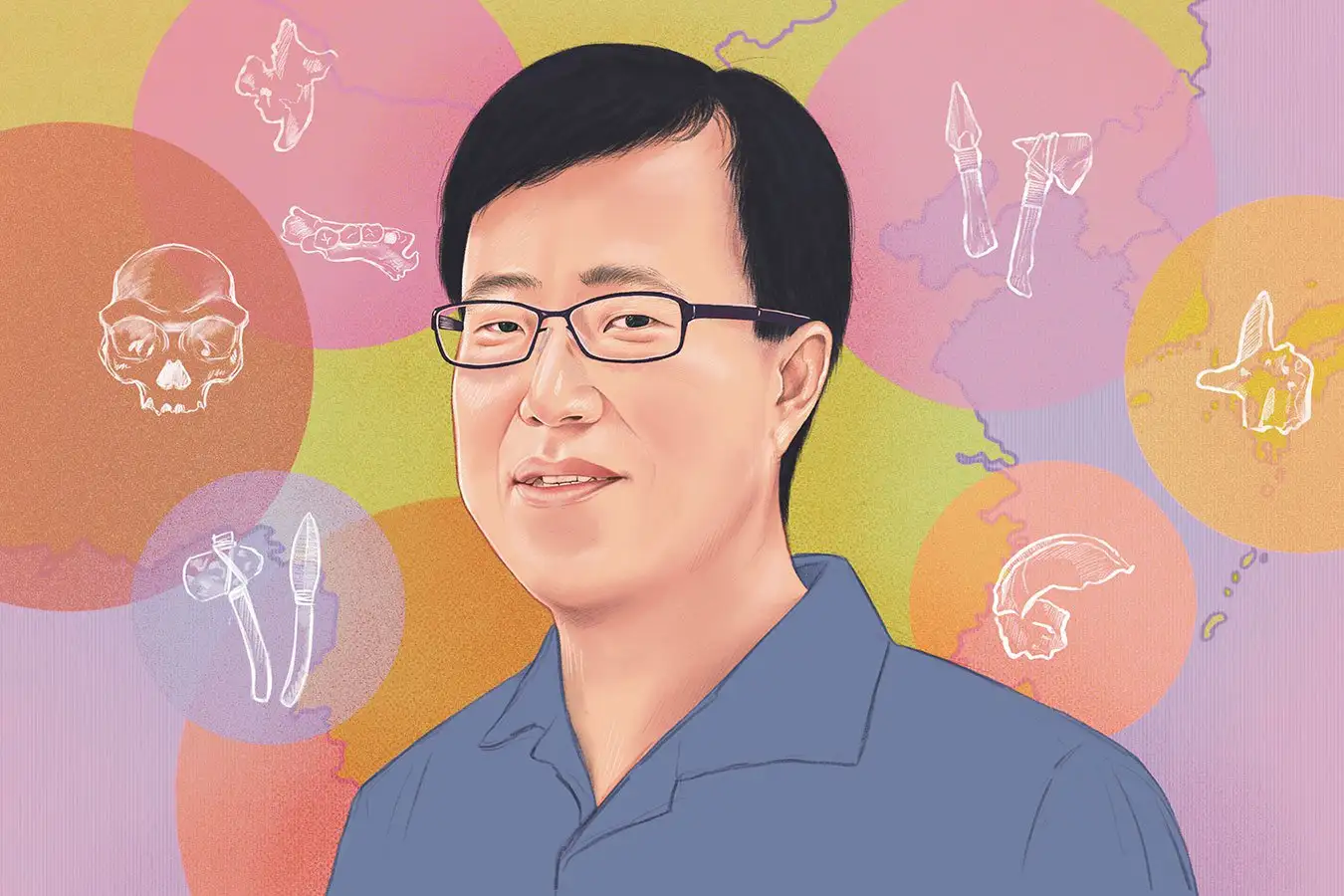

Or did they? Anthropologist Christopher Bae at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa is one of those who disagrees with the conclusions. He still feels the skull in question belongs where it was previously, that is, attributed to a species called Homo longi. In fact, Bae is at the heart of the tumultous debates about what our family tree ought to look like. In the past five years, he and his colleagues have suggested we add two ancient human species into the mix: Homo bodoensis and Homo juluensis.

Both suggestions caused controversy, partly because Bae and his colleagues wilfully broke the formal rules that govern how species are traditionally named. He is unrepentant, however, arguing that the rules themselves have become fossilised relics that make no allowance for removing species names that are now considered offensive, or for ensuring that names are easy for everyone to pronounce. He spoke to New Scientist about all this – and how his interest in human evolution was sparked by the mysteries in his own origin story.

Michael Marshall: What was it that first drew you into studying ancient humans?

Christopher Bae: The basic goal of palaeoanthropology is to reconstruct the past, even without all of the pieces of the puzzle. Being originally adopted, where the first year of my life is a complete blank, the field resonated with me. In my own case, I was born in Korea, then I was abandoned when I was about a year old, and I lived in an orphanage for about six months before being adopted by an American family.

When I was an undergraduate student, I was able to go to Korea for the first time on an exchange programme, and during that trip I went to the adoption agency where I came from. I asked the manager whether there was any chance that I could actually find my biological parents. They said, to be honest, your Korean name is not real and your date of birth is not real. You shouldn’t even bother trying. There’s absolutely no chance. I kind of gave up at that time.

So I was interested in my own roots and I couldn’t figure out how to find them. But then I took an introduction to biological anthropology course, and I found a field where I could actually explore origins. It’s kind of like building my own origins.

Two species that often pop up in discussions about our direct ancestors are Homo heidelbergensis and Homo rhodesiensis. But in 2021, you were part of a team that proposed replacing them both with a new species named H. bodoensis. Why?

My colleague, Mirjana Roksandic [at the University of Winnipeg, Canada], and I organised a session at a 2019 anthropology conference focused on the H. heidelbergensis question. There was general agreement that H. heidelbergensis is what we call a “wastebasket taxon” because anything from the Chibanian Age [775,000 to 130,000 years ago] that doesn’t clearly belong to Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis or Homo sapiens tended to be assigned to it.

So what happens to the H. heidelbergensis fossils that do constitute a distinct group of hominins, do they get a new name?

If we get rid of H. heidelbergensis, the next name, based on the rules of priority, is H. rhodesiensis. But that species was named after Northern Rhodesia, the old name of present-day Zambia, which itself was named after Cecil Rhodes. Now, do we really want to name the potential ancestor of modern humans after a known colonialist like Rhodes? So, when we were putting that paper together, we said, you know what, we’ll come up with a new name, and we’ll name it after Bodo [a 600,000-year-old skull from a site in Ethiopia].

What was the reaction to your paper?

When it went out for review, half the reviewers said, this has got to be published because we have to have this discussion out there. The other half of the reviewers said, this is ultimate garbage, it should not be published. Not surprisingly, there was a back-and-forth as soon as the paper came out.

Is there any emerging consensus yet?

We had a workshop in 2023 in Novi Sad in Serbia. We had about 16 or 17 palaeoanthropologists working on this topic. We all agreed that H. heidelbergensis has become a wastebasket taxon. The other major conclusion was that H. rhodesiensis should be removed from circulation because of Rhodes’s colonial history. In fact, only one of the palaeoanthropologists in attendance thought rhodesiensis was not problematic.

The Xujiayao site in northern China

Christopher J Bae

It is the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) that ultimately judges cases like this. Has it responded to your H. bodoensis argument?

The ICZN published a paper in the Zoological Journal of the Linnaean Society in 2023, a pre-emptive strike, and it said: We’re not going to remove any names from circulation where there may be ethical issues. We actually ended up going down a rabbit hole as a result of this, and challenging the ICZN. [Editor’s note: The ICZN’s 2023 statement recognised that scientific names might cause offence, but said it is outside the scope of the commission to assess the morality of persons honoured in eponyms. It also emphasised the importance of zoologists following its code of ethics when naming new species.]

Are species names really important enough to fight over?

Yes and no. For instance, there’s a beetle from a few caves in Slovenia. In the 1930s, an Austrian entomologist [Oskar Scheibel] said, I’m going to name this as a new species, after Adolf Hitler. Nowadays, the beetle [Anophthalmus hitleri] is a hot product as a keepsake. On the black market, people are selling them because a lot of neo-Nazis want to collect them. It’s eventually going to lead to the extinction of these poor innocent beetles, who haven’t done anything to bother anybody.

What’s the alternative?

I would say, talk with your local collaborators and find a species name that would be acceptable for them, because they’re the ones who are going to have to deal with it and live with it on a regular basis. I would hope that we stop using people’s names to name species or we’ll continue to run into problems down the road. I think that’s the direction that we’re going to go – and change is in the air. The ICZN is trying to change how they can attract members from the Global South and give them more of a voice. And some other major associations such as the American Ornithological Society have recently voted to remove egregious species names from the biological organisms they study.

You fell foul of the ICZN rulebook again last year, regarding some ancient human fossils from a site in northern China called Xujiayao. What’s the story there?

Researchers found a bunch of different hominin fossils at that site in the 1970s representing more than 10 individuals, but the fossils were all separate pieces. My colleagues and I, including Xiujie Wu [at the Chinese Academy of Sciences], worked on these fossils. Wu actually did a virtual reconstruction of the posterior part of one skull. And when we looked at it, we said, wow, this looks really, really different from other similar-aged hominins.

What sort of differences are we talking about?

Size and shape differences. Our average cranial capacity is about 1300 to 1500 cubic centimetres. These guys have a cranial capacity between 1700 cm³ and 1800 cm³ – so much, much larger than your average human. Furthermore, based on a shape analysis, it was clear that the Xujiayao fossils – and fossils from a nearby site named Xuchang – consistently fell away from the other fossils and grouped together. That’s what led us to naming a new species.

Bae examines a human fossil found in Serbia that may belong to Homo bodoensis

Christopher J. Bae

But the name you chose was controversial. Can you explain why?

Where species names actually come from is quite fascinating. In this case, we could have named it after Xujiayao – which is the type site – and then added “-ensis” at the end, making it Homo xujiayaoensis. This follows the ICZN rules.

And in Latin, that means “Homo belonging to Xujiayao”. But you didn’t like that option?

The problem is, only people who speak Chinese will be able to pronounce it, let alone spell it correctly. Names actually mean something. You need to be able to pronounce and spell them. So we came up with “julu”, which literally means “big head”.

If we follow the ICZN rules, though, then we are required to add an “i” at the end, making “Homo jului”. However, in our view, again, people would not be pronouncing it correctly unless they understood Chinese. Some people might say “julu-eye”, others would say “julu-ee”. This is why we chose Homo juluensis.

How does your new species relate to the mysterious Denisovan humans, who lived in what is now East Asia during the Stone Age?

If you look at the second molars from the Denisova cave in Siberia and the second molars from Xujiayao, they look almost exactly the same. You could actually take the Xujiayao molar and put it in Denisova, and then take the Denisova molar and put it in Xujiayao, and few people would know the difference.

But earlier this year, another group of researchers linked those same Denisovan fossils to a different ancient species from China called Homo longi – and that idea seems to have gone down well with many researchers.

In China, actually, most palaeo people agree with our H. juluensis argument. A lot of Westerners that are familiar with the Chinese record also tend to agree.

But what about evidence from the skull that appeared in June? Researchers extracted ancient proteins from a skull attributed to H. longi and found a match with proteins extracted from known Denisovan fossils.

When you talk to most geneticists, they say that you could probably discount the protein analysis for species-level identification. You can get at a broader level, like a cat and a dog, but it’s really hard to identify distinctions at a finer level.

Replica of a Denisovan molar, originally found in Denisova Cave in 2000

Thilo Parg CC BY-SA 3.0

Would you still accept H. longi as a valid species?

Oh yeah, I actually like H. longi and the fossils assigned to it. The debate revolves around what other fossils, if any, should be assigned to longi or whether some of these other fossils should be assigned to juluensis. It is interesting nowadays that the longi supporters seem to be trying to lump everything into longi, despite clear morphological variation in the Chinese fossils.

I’ve seen a few strongly negative reactions from other palaeoanthropologists to some of your research. How do you and your colleagues respond to that?

At this point in our careers, we’ve developed thick skin.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2500833-does-the-family-tree-of-ancient-humans-need-a-drastic-rewrite/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-11-03 16:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.