Feedback is New Scientist’s popular sideways look at the latest science and technology news. You can submit items you believe may amuse readers to Feedback by emailing feedback@newscientist.com

Too tight to mention

Feedback is one of many holidaymakers to have run afoul of French swimwear rules. For those unaware, men using a public swimming pool in France (and some parts of Italy) are compelled by law to wear tight swimming briefs. Loose shorts are forbidden. This is why you will never find Feedback in a French swimming pool.

Feedback was going to refer to these tight-fitting garments as “budgie smugglers”, a piece of Australian slang that has made its way to the UK. Then we learned that there is actually an Australian swimwear brand called Budgy Smuggler, whose bestsellers include swimming briefs decorated with brown and pink hibiscus, and we decided not to go there.

Anyway, let us meander in the general direction of the point. Subeditor Thomas Leslie came across a paper on medRxiv, describing “a cross-over study among male academics” on the relative merits of swimming briefs and shorts. We cannot begin to imagine what search terms Thomas used to discover this paper.

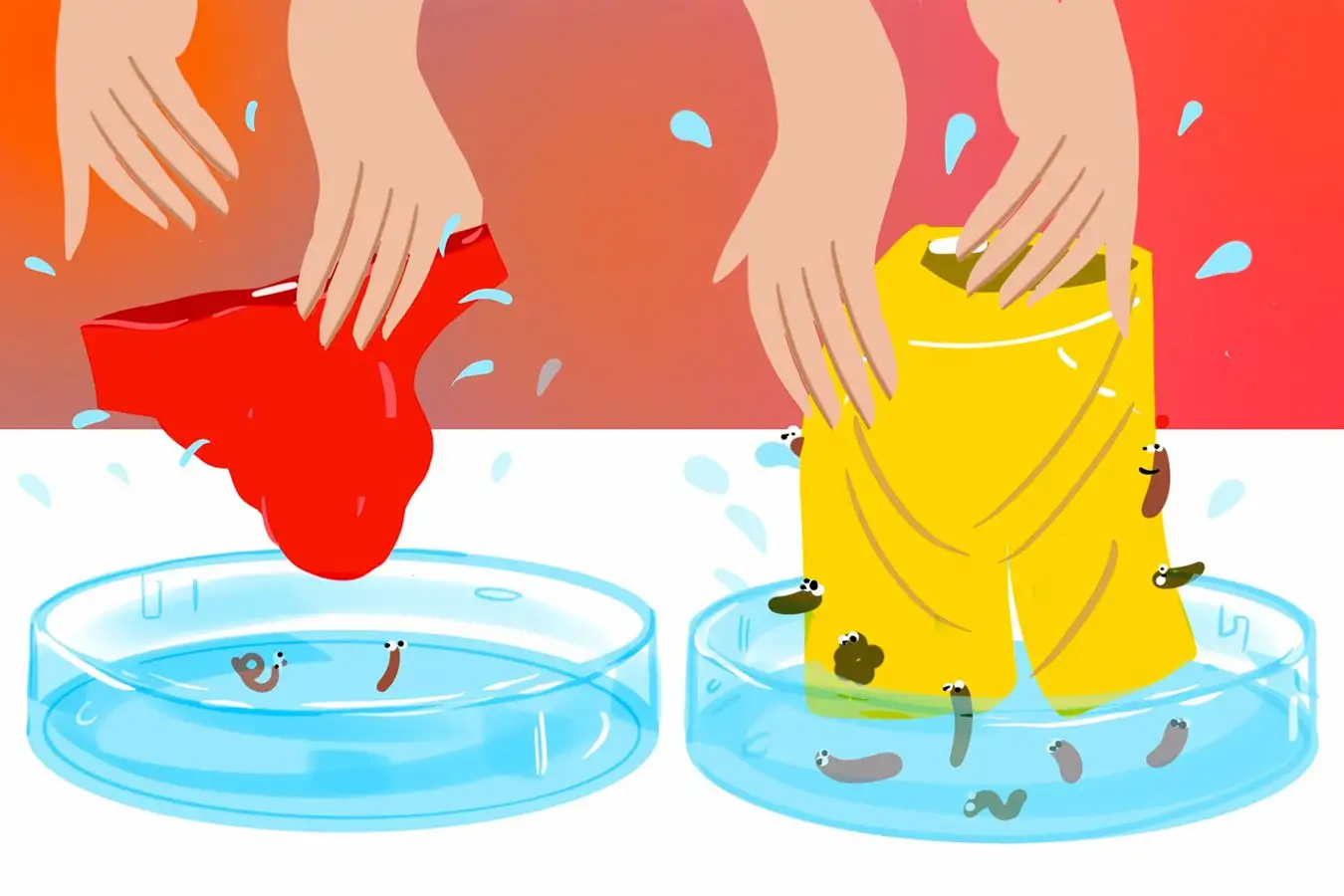

Let’s dive in. The authors explain that France insists on briefs for hygiene reasons, because “looser garments may introduce external contaminants into the pool and its environment”. However, “these claims have never been substantiated”. The team therefore recruited 21 male academics, luring them with the promise of free briefs. They were asked to wear either shorts or briefs under their clothes for 2 hours, then remove them and immerse them in water. The researchers tested the water for bacteria and found that water from shorts had more bacterial growth than that from briefs.

As a follow-up, five of the participants tried swimming in “local waterbodies”. However, this proved “rather eventful”. One volunteer had his clothes stolen, “leaving the participant in a slightly embarrassing outfit in public”. A second experiment was ruined when a participant left his briefs to dry on a rock while swimming in his shorts, whereupon “a dog (Canis lupus familiaris) briefly urinated on [them]”.

Feedback must confess to being mildly confused by the experiment. If shorts carry a heavier bacterial load, but you have to squeeze them out in water to release the microbes, is that really a problem? The authors themselves say they aren’t sure what’s going on. “It is possible that contaminant release from the gastrointestinal tract is lower in [briefs] due to their elasticity exerting external pressure on the gluteal muscles, thereby reducing contact between the rectum and the fabric.” That does seem possible.

Alternatively, maybe fluid dynamics plays a bigger role in bacterial release from shorts. “Surprisingly, the impact of pool hydrodynamic drag on fecal bacterial shedding is grossly unexplored and to the best of our knowledge, no studies have ever examined fluid dynamics inside different types of swimwear,” the authors write. Someone, please: write that grant proposal.

A bold bald build

It has finally happened: Lego has signed a deal with the owners of Star Trek, and their first release is a big model of the Enterprise-D from The Next Generation.

Full marks to the designers for starting with something so difficult: the Enterprise-D has a sleek design, with curves everywhere and barely a straight line to be found, so building it out of (mostly) rectangular blocks is a big swing.

Alas, in solving this design challenge, the Lego people missed a fine detail. Hidden inside the model is a gold plaque that reads “To boldy go where no one has gone before.”

Funky rodents

Suppose you’re worried that your lab mice are bored, so you decide to play them some music to keep them entertained. What should you put on?

That’s the question asked by Johann Maass and his colleagues in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, in a paper called “Taylor Swift versus Mozart: music preferences of C57BL/6J mice”.

They point out that, when researchers play music to mice, they generally choose the same piece: Sonata for Two Pianos in D major, K.448 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. This is the piece that supposedly boosts your child’s intelligence if they listen to it – you know, the famous “Mozart effect” that was resoundingly debunked years ago. (The key evidence against it came in a 2010 study titled, gloriously, “Mozart effect–Schmozart effect: A meta-analysis”.)

It’s kind of weird that biologists are so keen to play this non-brain-enhancing Mozart piece to mice. As the authors point out, “mice have a hearing range of about 2 kHz to 100 kHz” and much of the sonata is below 1 kHz – so the mice probably can’t even hear most of it.

Consequently, the researchers created the Mouse Disco Testing Arena: four soundproofed rooms, connected by tunnels. Each had different music playing. One had the Mozart. Another had electronic dance music, “represented by the first 60 min of The Very Best of Euphoric Dance: Breakdown 2001 – CD1“. A third had a selection of what the team calls “classic rock” and what Feedback would call “naff rock”, including songs by Nazareth, FireHouse and (horror of horrors) Whitesnake. The fourth had a Taylor Swift playlist.

The mice showed no preferences – except that they spent almost no time in the Mozart room. Take that, Amadeus.

Got a story for Feedback?

You can send stories to Feedback by email at feedback@newscientist.com. Please include your home address. This week’s and past Feedbacks can be seen on our website.

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg26835714-100-the-science-of-swimming-trunks-including-tightness-analysis/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-11-26 18:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.