At first glance, it might not seem like people have much in common with deer. But a strange discovery about how their antlers regenerate is lifting the lid on the unseen ways that our bodies work, too.

Biologist Chunyi Li, who has long studied deer in north-east China, noticed something odd that happened when the animals regrew their antlers each year. This regrowth coincided with healthier-looking animals that showed much faster healing of their wounds and less scarring, leading him to suspect that the regenerating antlers somehow promoted regeneration in the wider body.

Li’s hunch was confirmed last year when he and his colleagues at Changchun Sci-Tech University in Jilin, China, found that the growing antlers release messages that tell other parts of the body to shift into regenerative wound-healing mode – evidence of a hitherto-hidden communication network that connects distant organs.

This finding doesn’t apply only to deer. In recent years, researchers have discovered a web of chatter among the human body’s organs and tissues, even those we once thought were dull and inert. We now know that your fat and brain tissue converse to influence the speed at which you age, your skeleton sends information packets to the pancreas to control metabolism, and much more.

By tapping into these communication networks, we may be able to develop radical new ways to boost our health and slow ageing – and some clinical trials of this approach are already under way.

Crosstalk between organs

These ongoing findings are emerging from the new field of inter-organ communication, which is building on the old physiological idea that organs function together as a greater whole.

We have long known that information is transmitted around the body via nerve networks and hormones, but what is extraordinary about these latest discoveries is the growing diversity of ways in which organs and tissues “talk” to each other to coordinate their action. Indeed, inter-organ communication is now seen as critical machinery for controlling metabolism, ageing and overall health.

The ageing process is orchestrated via “conversations” between different organs and tissues

Chris Howes/Wild Places Photography/Alamy

“I think we’ll suddenly see that organs are communicating in ways we didn’t know about,” says Irene Miguel-Aliaga at the Crick Institute in London. “And then if we find that, then we can see what goes wrong in disease.”

The first clues that there might be more to some organs and tissues than first supposed arose in the mid-1990s, when researchers discovered that fat, or adipose tissue, makes a hormone called leptin, which helps control appetite and the body’s energy balance. This transformed our perception of fat: once seen as passive storage tissue, it is now thought of as a dynamic, vital organ.

Since then, it has emerged that pretty much every organ or tissue is chipping in. One of the biggest surprises is bone, long thought of as a lifeless mechanical scaffold. In fact, we now know that bone functions as a sophisticated “endocrine” organ, secreting a hormone called osteocalcin that influences metabolism, male fertility and exercise performance. It even reaches the brain, where it reduces anxiety, improves spatial memory and enhances cognition. Boosting falling levels of osteocalcin may one day offer a way of tackling age-related decline in muscle and brain function.

Our skeleton isn’t just a mechanical scaffold, but a dynamic organ that orchestrates many processes in the body

Michael Heise/Unsplash

The skeleton has its fingers in so many pies because the energetic cost of running it is exorbitant. To repair tiny fractures caused by mechanical stress, bone is constantly being broken down by cells called osteoclasts, and in turn constantly rebuilt by cells known as osteoblasts. “Bone health has to be connected to energy metabolism in a way that bone can grow, but not at the expense of the other organs and function,” says Gerard Karsenty at Columbia University in New York. This is why it has such a powerful influence on so many other organs and tissues. And, importantly, other organs talk back.

One such organ is fat, which talks to bone via leptin. Back in 2002, it was discovered that fat sends signals to the brain, which responds in part by increasing nerve activity in the sympathetic nervous system, whose tendrils reach many organs, including bone. There, its nerve endings send signals to osteoblasts, reducing bone building and increasing bone destruction. This means that leptin signals from fat are a major regulator of bone mass.

Osteoporosis treatment

A study from 2018 showed that these signals can be jammed with existing blood-pressure drugs known as beta-blockers, which inhibit stress hormones like adrenaline released by the sympathetic nervous system. So these drugs might be a cost-effective way of preventing bone loss in women after menopause and in older people more generally. Two clinical trials investigating this are currently under way.

Osteoporosis isn’t the only condition that could benefit from intervening in inter-organ signalling: ageing itself could be a target. This springs from the surprising discovery in 2013 that a small region of the brain known as the hypothalamus appears to integrate conversations from multiple organs, and so acts as a high-order controller of ageing and, in turn, longevity.

“

Osteoporosis isn’t the only condition that could benefit from intervening in inter-organ signalling: ageing itself could be a target

“

Shin-ichiro Imai at Washington University in St Louis, Missouri, whose team was one of the two that made the discovery, thinks of this orchestration as an entire interconnected system that maintains a stable function, or “robustness”. When this robustness falters, it results in ageing and physiological decline. “We need to integrate all the different pieces from all the different layers, like a molecular layer, cellular layer, tissue, organ layer, to understand the whole system,” he says.

Longevity controller

Imai and his colleagues have put many of these pieces together. For example, in 2024, they showed that a particular subset of neurons in the hypothalamus of mice talks to adipose tissue through the sympathetic nervous system, triggering the release of an enzyme essential for producing NAD+, a molecule that is vital to cellular metabolism and associated with longevity. When the researchers stimulated these neurons in old mice, the mice lived longer than control mice that didn’t receive this stimulation.

“This is the first demonstration in mammals that manipulation of specific neurons really delays ageing and extends lifespan,” says Imai. Moreover, the 2024 study concluded that “these findings clearly demonstrate the importance of the inter-tissue communication… in mammalian aging and longevity control”.

Other organs, including skeletal muscle and the small intestine, also converse with the hypothalamus. For instance, in unpublished work, Imai and his colleagues have identified the hormone used by skeletal muscle to communicate with this brain region.

Each of these communication pathways operates independently but synergistically to maintain the overall system’s robustness, says Imai, which we can tap into in turn. So, rather than someone taking supplements to boost NAD+ in the hope of slowing down the ageing process – a strategy whose efficacy is still being investigated in humans – Imai proposed a new approach last year, which he terms “inter-organ communication management”. This would involve interventions to strengthen each of these brain-organ conversations simultaneously “as an anti-ageing preventative measure”, he says. “We are working to translate this idea to humans.”

The body’s diverse languages

To do this, we need to fully understand all the different communication systems that organs use to send messages around the body. We now know that organs use a bewildering smorgasbord of languages to communicate, not just the well-known routes of hormones and nerve action. These include metabolites, small molecules carrying information about energy status and cellular health, and new signaling molecules, such as those produced when skeletal muscles contract that act on many other tissues, including the brain and liver.

New types of these messengers are constantly being uncovered, thanks to advances in analytical technologies. For instance, in January, researchers showed how a type of body fat called beige fat regulates blood pressure via a protein it produces called QSOX1, which helps control the stiffness of blood vessels. And a study from November last year found that cancer cells manipulate inter-organ signaling — in this case, via nerves — to undermine the immune response against them.

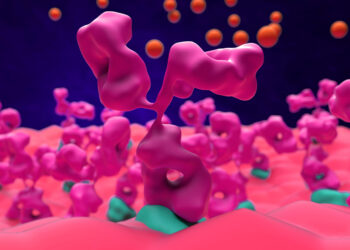

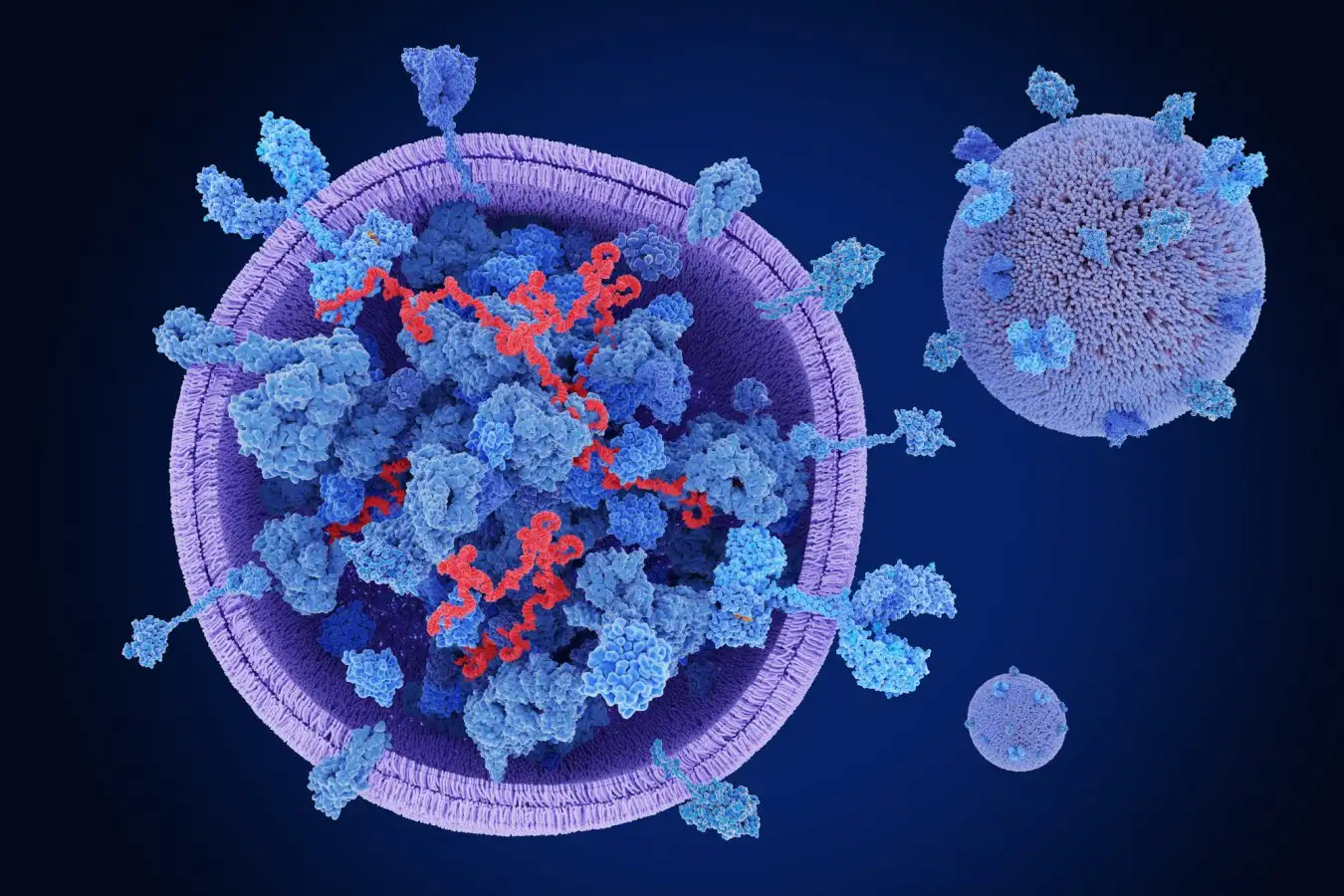

But one of the most exciting discoveries in the field of inter-organ communication is the way that many of these factors are shunted around the body in mysterious bubble-like blobs known as extracellular vesicles (EVs), which our cells constantly shed. When they were first spotted in cells in the 1980s, researchers assumed the cells were just spitting out junk. But we now know there is a whole constellation of EVs of varying sizes, carrying a range of cargoes, from large vesicles bearing mitochondria (the energy engines of the cell) to smaller ones known as exosomes that carry tiny fragments of RNA called microRNAs, which can influence gene activity in recipient cells.

Bubble-like blobs called extracelllular vesicles are a key way for organs to send messages around the body

Shutterstock/Juan Gaertner

Here, too, new varieties of EVs are continually being unearthed, such as the discovery last year of particularly massive ones dubbed “blebbisomes”, which function as mobile communication centres. At the opposite end of the spectrum are the tiny exomeres and supemeres, both discovered in 2021, which aren’t encased in membrane. Plus, there are oncosomes, produced by cancer cells. All are emerging as important players in health and disease.

In a 2022 study, for instance, Saumya Das at Harvard Medical School and his colleagues showed that heart cells and a type of cell from connective tissue called a fibroblast communicate via EVs to limit the amount of scarring in heart failure. But EVs can cause problems, too. In 2023, Das and his team showed that EVs produced by the heart can make their way to the kidneys and cause damage by delivering harmful microRNAs – damage that could potentially be prevented by therapeutic intervention.

Obesity, too, exerts some of its effects on the body via EVs. These can communicate with multiple organs, crossing the blood-brain barrier to talk to immune cells in the brain called microglia, which are involved in brain inflammation. “We’re looking at the whole connection between obesity and dementia,” says Das. Fat also talks to the liver via EVs, which are emerging as an important factor in a form of liver disease caused by metabolic dysfunction. And fat-derived EVs also seem to play a role in the development of heart arrhythmias in obesity.

Recent studies also show that EVs are implicated in neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s, transporting microRNAs and pathological proteins from the brain to peripheral organs. This helps explain the progression of these conditions beyond the nervous system.

The ageing process

We are even finding that these once-mysterious blobs play a pivotal role in ageing. A key factor in ageing is the accumulation of senescent, or “zombie”, cells, which promote inflammation and damage in tissue, leading to age-related decline. Senescent cells release EVs that, like sparks from a wildfire, trigger senescence in other cells, even in distant organs. Senescent cells in the lungs of people with chronic lung disease emit EVs that trigger senescence in distant blood vessels, for example. This probably contributes to what is known as the “multimorbidity of the elderly”, the fact that older people usually have several chronic conditions, such as heart disease combined with muscle wasting and kidney disease.

Still, there is a long way to go before we fully understand the variety of EVs within the body and their precise roles. But this work underlines the idea that no organ is an island. “You really cannot think of [diseases of these organs] as siloed,” says Das. For example, the leading type of heart failure was long believed to concern the heart only. “But the more you look at it, it’s a systemic disease,” says Das. “It has obesity, it has liver dysfunction, it has kidney dysfunction, it even has dementia.” This may explain why GLP-1 drugs, although originally designed to aid weight loss and treat diabetes, are now being used to successfully treat heart failure.

This all raises the question of why our organs need to speak so many different languages. One possibility is that the location of the conversation matters. “Maybe there’s a spatial logic to this communication, and then for that reason it matters what organ is next to what organ,” says Miguel-Aliaga. In 2024, she and her team found that, in fruit flies, adjacent organs influence each other’s shape by secreting specific substances, and that changing their geometry can make them function differently.

“We really don’t understand this spatial specificity very well. But I think it’s going to be important because I think it’ll add a layer of information in between the organ and organism level that we still don’t know about,” says Miguel-Aliaga. “Potentially, it’s a language in itself.”

One reason why this kind of communication system might be useful is that it offers yet more versatility in targeting particular messages to specific “audiences” of tissues and organs. Some signals, such as conventional hormones, are broadcast body-wide like a national radio show. Others could be locally confined, with organs whispering to each other like next-door neighbours over a garden fence.

While we don’t yet know for sure why so many languages are needed, their existence highlights the complexity of coordinating a collection of organs in space and time into a whole organism. And it suggests that, while we thought we already knew everything about what our organs do, they are each likely to have a range of extra functions that we haven’t yet discovered.

Restoring good communication – local, organ-wide and body-wide – could also help us understand more about regeneration and perhaps how to make humans better at it. Experiments linking the blood systems of both young and old mice have revealed the presence of signals that can rejuvenate some tissues and extend lifespan. And studies of animals that excel at regeneration are starting to show that, in many cases, it is a process involving coordinated responses from different tissues and organs, even those remote from the injury.

Antler regrowth in deer seems to trigger a wider regeneration, including better wound healing

Danny Green/2020VISION/Nature Picture Library/Alamy

Amputating an axolotl’s leg, for instance, triggers a body-wide reaction. The cells at the injury site revert to a more embryonic-like state, called a blastema, which gives them the flexibility to regenerate the limb – something mammals can’t do. At the same time, cells in the opposite limb and in organs such as the liver, heart and spinal cord also start dividing. Intriguingly, although mice don’t have the same reaction, if you damage a muscle in one limb, stem cells in the opposite limb enter an “alert” state that means they can respond to injury faster. This is triggered by a signal in the blood.

Li’s work on deer antlers reveals similar principles, showing that both local conversations between neighbouring tissues and body-wide communication are involved in this spectacular act of regeneration. Applying extracts of blood from deer that are regenerating their antlers to wounded rats makes the rats’ wounds shift to a regenerative form of healing that repairs them almost scar-free. Li and his team are now working on a formula to test this in humans.

New therapies from inter-organ communication

Indeed, the challenge ahead for this field is to translate discoveries into new therapies, but this is beginning to happen. For instance, an ambitious project across five research centres in Germany was kick-started last year to investigate the role of faulty inter-organ communication in the irreversible muscle loss linked to conditions such as cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Certain metabolites associated with these conditions can reprogram immune cells, which then promote muscle wastage. The project aims to identify these metabolites, with the ultimate goal of developing therapies that target them. And in the US, the National Institute on Aging has also identified inter-organ communication as a research priority.

It took four decades of patient observation for Li to discover the secret of the deer’s mysterious annual rejuvenation. It turns out our own bodies have been just as cryptic, with our organs talking between themselves without us noticing. Now that we are learning to listen, we can find ways to turn their conversation to our advantage.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2513188-the-secret-signals-our-organs-send-to-repair-tissues-and-slow-ageing/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2026-02-02 16:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.