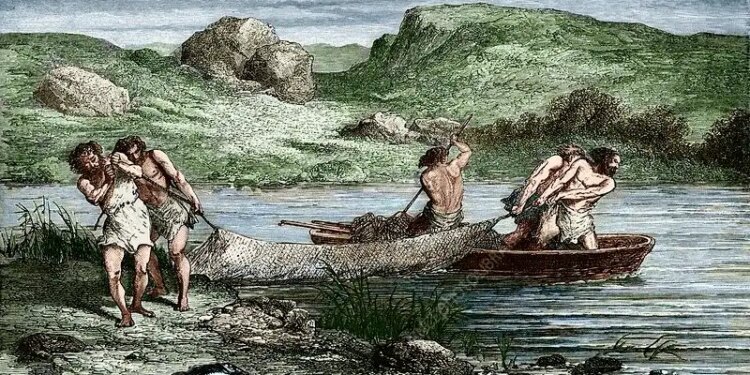

The ancestors of the British Bell Beaker people lived in a wetland area and relied heavily on fishing

SHEILA TERRY/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

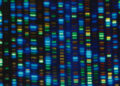

Analysis of ancient DNA has uncovered the origins of a mysterious group who appeared in Britain around 2400 BC and, in a century or less, all but replaced the people who built Stonehenge.

These people were associated with the Bell Beaker culture, which emerged in western Europe in the early Bronze Age and is named for the shape of the typical pots they left behind. This culture probably originated in Portugal or Spain, but the new study reveals that the people who took over Britain came from just across the North Sea, in the river deltas of the Low Countries. This resilient population had preserved some of its hunter-gatherer lifestyle and ancestry for millennia after early farmers had swept across Europe.

David Reich at Harvard University and his colleagues studied the genomes of 112 people who lived in what is now the Netherlands, Belgium and western Germany between 8500 and 1700 BC.

Before joining the project, Reich wasn’t too excited, he admits: “The Netherlands seemed like the most boring place in the world – every single bit of ground there has been walked on a million times before. But it turned out to be perhaps the most interesting place in Europe.”

The DNA sequenced by his lab revealed a population forged in the Rhine-Meuse delta in the Dutch-Belgian borderlands, originating from a resourceful group of hunter-gatherers surviving in the waterlogged wetlands around these big rivers, feeding on fish, waterfowl, game and various plants.

Neolithic farmers originating in Anatolia spread across Europe from around 6500 BC, probably because their ability to produce their own food meant they could raise many more children than hunter-gatherers did. In just a few centuries, hunter-gatherer genetic ancestry disappeared or was strongly diluted in each place where the farmers arrived.

But not, the ancient DNA reveals, in these wetlands, where the influx of farmer genes remained sparse for several thousand years. The dynamic, regularly flooded landscape of rivers, marshes, dunes and peat bogs was a nightmare for early farmers, but rich in opportunities for those who knew how to survive there, says team member Luc Amkreutz at the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, the Netherlands. “These hunter-gatherers were carving their own path, from a position of strength.”

Judging from the DNA, these people were far from marginalised. Their Y chromosomes, passed down from father to son, remained largely hunter-gatherer for another 1500 years or so after the arrival of farmers in the region, while their mitochondrial DNA and X chromosomes reveal a steady trickle of farmers’ daughters joining them. “This really was a surprise to us,” says team member Eveline Altena at Leiden University Medical Center. “Something you can’t really tell without DNA.”

This was probably a mostly peaceful process involving communities where women tend to move while men stay in their homesteads, says Reich, although an element of force can’t be ruled out. This exchange may have gone both ways, but DNA preservation is much worse in the drier areas where farmers lived, so this remains unknown for now, he says.

Bell Beaker pottery from Germany

Peter Endig/dpa picture alliance/Alamy

Archaeological remains reveal that, over time, the hunter-gatherers did gradually adopt pottery, grow some grain and raise some animals, but without abandoning their original lifestyle.

Then, around 3000 BC, a tribe of nomadic herders called the Yamna, or Yamnaya, from the steppes of what is now Ukraine and Russia started migrating to the west. Their encounters with eastern European farmers gave rise to the Corded Ware culture, named for the cord-like decoration of its pottery. Their descendants which swept across much of Europe, but hardly made a dent in the delta.

The study identified one skeleton from this time with a Yamna Y chromosome, and excavations have also revealed pots, some of which were used to cook fish – another example of the wetlanders using new objects from abroad in their own way. Overall, though, few people had much, if any, steppe ancestry.

That changed when, around 2500 BC, the Bell Beaker culture appeared. These people introduced steppe ancestry into the wetland people’s DNA, but a significant 13 to 18 per cent of their characteristic hunter-gatherer-early-farmer gene mix remained. They might have started fading into history right then. But it turns out they weren’t quite done yet.

A skeleton buried at Oostwoud in the Netherlands, whose DNA was analysed in the study

Provinciaal Archeologisch Depot North-Holland (CC by 4.0)

The new study reveals that the people who arrived in Britain around 2400 BC had almost the exact same blend of Bell Beaker and wetland community genes. And within a century, they would nearly – or even entirely – replace the Neolithic farmers who had built Stonehenge. “Our models indicate that at least 90 per cent, but up to 100 per cent, of the original ancestry was lost [from Britain],” says Reich.

It isn’t entirely clear if this started with the arrival of the Bell Beaker culture in Britain or if other people had been moving in earlier. Before the Bell Beakers arrived, people in Britain were cremating their dead instead of burying them, which means they rarely left DNA.

In any case, what happened was “very dramatic, unbelievable almost”, says Reich. The reasons for this rapid replacement have intrigued archaeologists since it was first suggested by a 2018 study. Reich suspects the involvement of a disease like the plague, to which people on the European continent may have been exposed before. People in Britain, meanwhile, may have been more vulnerable to it.

What probably didn’t play a role is religious fervour, says team member Harry Fokkens at Leiden University. “Existing monuments like Stonehenge and Avebury remained in use and were even expanded after the people who made them were gone.”

Michael Parker Pearson at University College London is intrigued by the extent to which the new population adopted Britain’s monument styles, such as henges and stone circles, even though they brought a completely new way of life with them, including new styles of pottery and dress.

The Bell Beaker people also introduced metals to Britain, he adds. “Some gold hair ornaments found in Beaker graves in Britain are nearly identical to ones found in Belgium.”

Human origins and gentle walking in prehistoric south-west England

Immerse yourself in the early human periods of the Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age on this gentle walking tour.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2515260-the-surprising-origins-of-britains-bronze-age-immigrants-revealed/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2026-02-11 16:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.