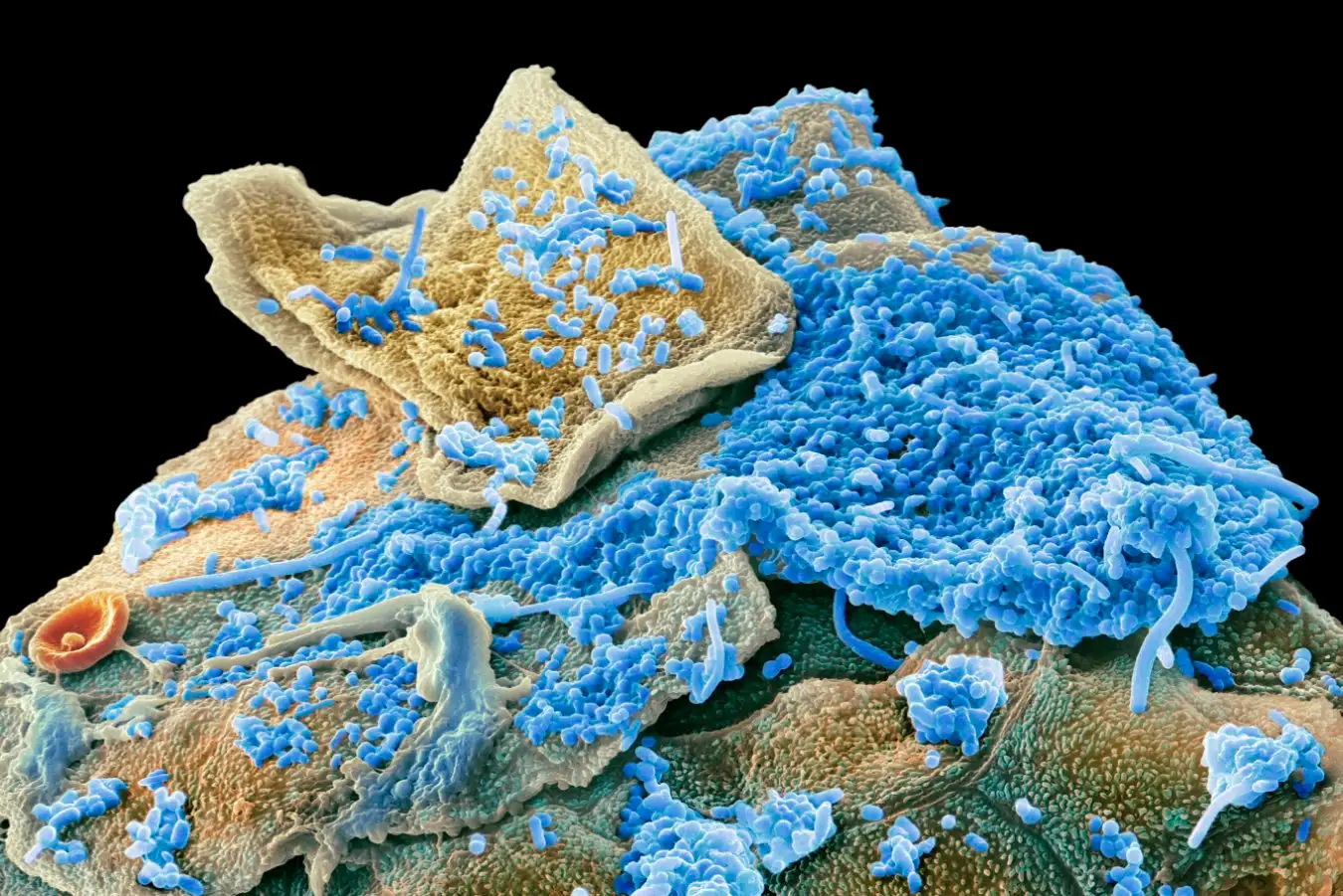

Oral bacteria (blue) on human cheek cells (yellow) shown in a scanning electron micrograph

STEVE GSCHMEISSNER/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Some people with obesity have a distinct oral microbiome signature – a discovery that could lead to a way to spot the condition early and potentially prevent it.

The huge community of microbes that resides in the gut can contribute to weight gain and has been strongly linked to obesity and other conditions relating to metabolism. So far, though, the evidence that the oral microbiome, which houses more than 700 species of bacteria, is involved in obesity or in general health has been more limited.

“The oral microbiome is the second largest microbial ecosystem in the human body, so we decided to study whether it is associated with systemic diseases,” says Aashish Jha at New York University Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates.

He and his colleagues took saliva samples from 628 Emirati adults, 97 of whom had obesity, and sequenced these to discover which microbes were present. The researchers compared these against 95 individuals from the group who were a healthy weight but were otherwise similar to the people with obesity in terms of age, sex, lifestyle, oral health and frequency of tooth brushing.

The comparison revealed that the oral microbiomes of the people with obesity featured more bacteria that drive inflammation, such as Streptococcus parasanguinis and Actinomyces oris, and more Oribacterium sinus, which produces lactate. Elevated lactate levels are associated with poor metabolism.

Jha and his colleagues also identified 94 differences in microbial metabolic pathways between the two groups. For example, people with obesity had boosted mechanisms for carbohydrate metabolism and the breakdown of an essential amino acid called histidine, but were worse at making B vitamins and heme, which is important for transporting oxygen.

Metabolites produced in greater numbers by the boosted processes in people with obesity included lactate, histidine derivatives, choline, uridine and uracil. These compounds are associated with indications of metabolic dysfunction, such as higher levels of triglycerides, liver enzymes and glucose in the blood.

“If we put this together, a metabolic pattern emerges. The data point toward a low‑pH, carbohydrate‑rich, inflammatory oral environment in the obese individuals,” says Lindsey Edwards at King’s College London. “This study provides some of the clearest evidence to date that the oral microbiome reflects, and may contribute to, metabolic changes associated with obesity.”

For now, this is only an association, so cause and effect still need to be disentangled. “Some of these associations are mind-blowing to me, but right now, we cannot say anything about what is causing what, so that’s the next step for us,” says Jha.

To disentangle whether it is the oral microbiome causing obesity or it is being changed by the condition, Jha and his colleagues are planning follow-up experiments that look at both saliva and the gut microbiome to see if there is any movement of microbes or metabolites from the mouth to the gut.

Jha thinks that could be possible, but says his hypothesis is that our mouth is full of blood vessels that support our ability to taste and quickly deliver nutrients to where they are needed, and these vessels may also enable metabolites to get straight into our bloodstream and affect the rest of the body.

Establishing causation will also require randomised-controlled trials and studies that dig into the metabolic pathways, says Edwards.

It could be that, when diet starts to change, some elements of the food can be better metabolised by certain bacteria, which flourish and start producing more metabolites that may influence our cravings for certain foods, pushing people towards the path of obesity, says Jha. Uridine, for example, is known to drive greater ingestion of calories, he says.

If it does turn out that oral bacteria can drive obesity, it might provide a route for interventions to prevent it, says Edwards, such as transferring healthy oral microbes via a gel, prebiotics that promote the growth of specific bacteria, targeted antimicrobials or pH‑modifying rinses. “No doubt behavioural interventions, such as reducing sugar intake, will also help.”

Even if the oral microbiome is an effect of obesity rather than a cause, assessing it could still be useful. The distinct microbiome shifts could be easily picked up by a saliva test, so could work as a way to detect obesity early to facilitate prevention, says Jha.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2512970-our-oral-microbiome-could-hold-the-key-to-preventing-obesity/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2026-01-22 16:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.