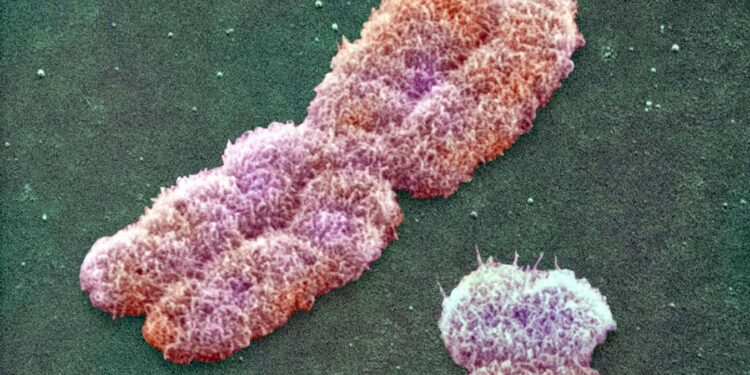

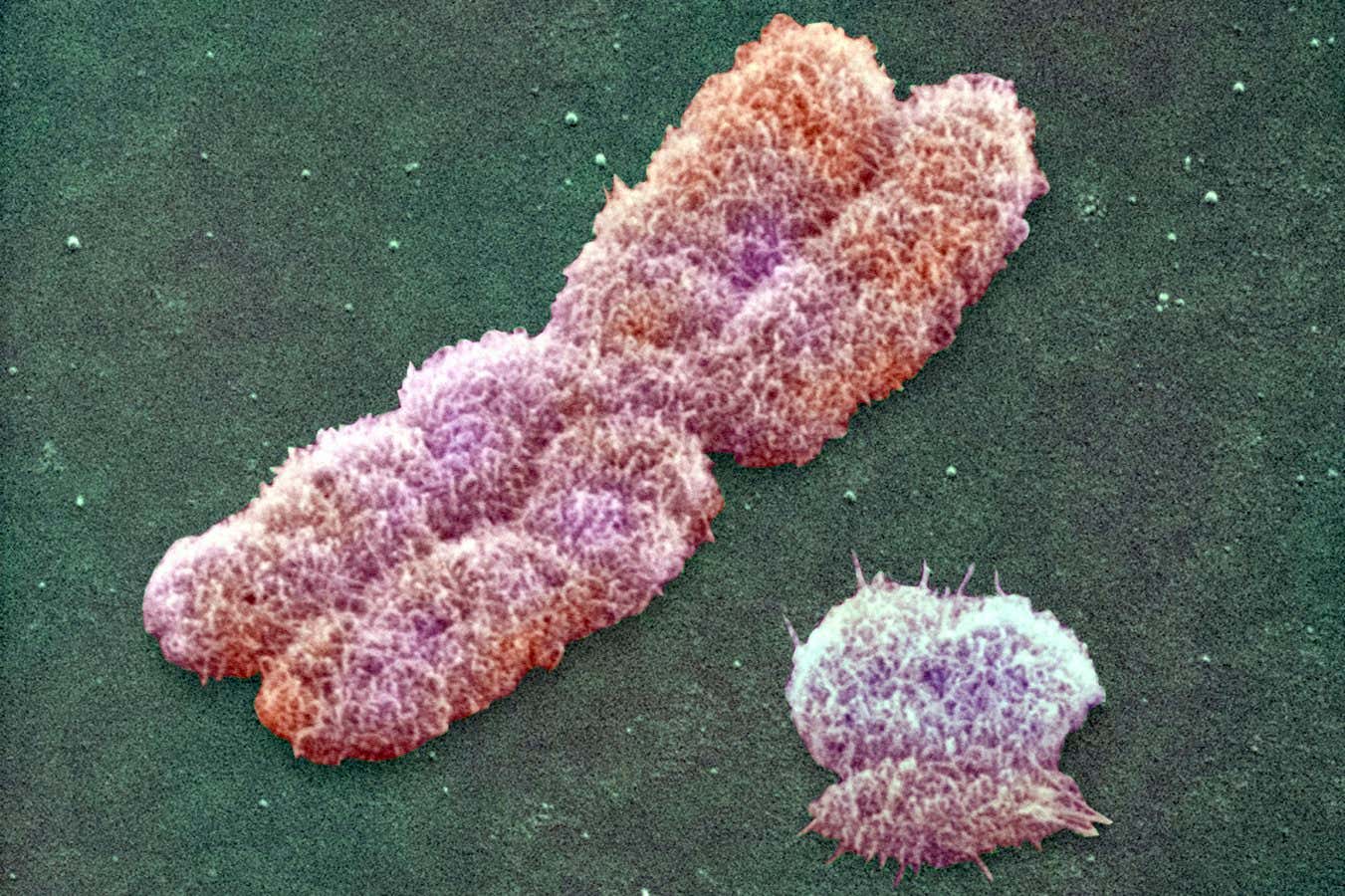

A human Y (right) and X chromosome seen with a scanning electron microscope

POWER AND SYRED/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Men who have lost their Y chromosome from a significant number of their immune cells are more likely to have narrow blood vessels, a key contributor to heart disease, according to a study of more than 30,000 people.

“Loss of Y is killing a lot of men,” says Kenneth Walsh at the University of Virginia, who wasn’t involved in the study. “Men live six years shorter than females, and an enormous amount of that mortality is due to their sex chromosome instability.”

The loss of the Y chromosome is the most common mutation that occurs post-conception in males. It typically takes place in white blood cells, immune cells that attack and eliminate pathogens, as the rapidly proliferating stem cells that generate white blood cells divide. Cells that lack Y accumulate with age, becoming readily detectable in roughly 40 per cent of 70-year-old men.

The issue began gaining attention in 2014, when Lars Forsberg at Uppsala University in Sweden and his colleagues found that older men with significant loss of Y in their blood died, on average, five-and-a-half years earlier than those without it. Walsh later linked it to heart disease.

Now, Forsberg and his colleagues are gaining further insights into the types of cardiovascular problems associated with the loss of Y. The team took advantage of the Swedish Cardiopulmonary Bioimage Study, which gathered detailed blood vessel scans from just over 30,150 volunteers aged 50 to 64, around half of whom were male. None of the volunteers showed signs of cardiovascular disease, but were still assessed for any blood vessel narrowing, or atherosclerosis.

Nearly 12,400 of the male participants had the genetic data needed to assess their degree of loss of Y. They were split into three groups: those with undetectable loss of Y in their white blood cells, those with loss of Y that affected 10 per cent or less of these cells, and those whose loss of Y affected more than 10 per cent of them. Each group’s atherosclerosis scores were then compared against each other’s and with those of the study’s female participants.

The researchers found that nearly 75 per cent of the men with the most loss of Y had narrowed blood vessels, compared with roughly 60 per cent of those who had 10 per cent or less of their cells affected by the mutation.

But atherosclerosis was still observed in around 55 per cent of the men with an undetectable loss of Y and in around 30 per cent of the women. “Obviously, [loss of Y] is not explaining the entire sex difference,” says Forsberg. “There are other factors.”

The study comes months after Thimoteus Speer at Goethe University Frankfurt in Germany and his colleagues looked at men who underwent an angiography – a type of X-ray used to check blood vessels – for suspected cardiovascular disease. They found that, over the subsequent decade, those with loss of Y in more than 17 per cent of their immune cells were more than twice as likely to die of a heart attack than those with fewer affected cells.

“The results of Lars Forsberg’s and our studies are quite consistent,” says Speer. “He sees more coronary atherosclerosis, and we observe a higher risk for patients to die due to myocardial infarction [heart attack], as the end point, I would say, of coronary atherosclerosis.”

Walsh notes that neither study definitively shows that the loss of Y caused these outcomes. However, statistical analyses carried out by both groups suggest it acts independently of smoking or ageing, the biggest risk factors for the mutation.

A key question now is how the loss of Y acts. Walsh’s earlier study found that removing the chromosome from mice’s immune cells harmed their cardiovascular systems by driving fibrosis, the formation of scar tissue. But heart attacks and atherosclerosis are much more associated with inflammation and faulty lipid metabolism than fibrosis. Both Speer and Walsh say more research is needed to understand this.

Once we gain a better understanding of the processes involved, Speer hopes that a blood test that looks for loss of Y will one day guide preventative interventions. “[It] might identify patients who will particularly benefit from specific treatments,” he says.

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2491701-vanishing-y-chromosomes-seem-to-be-driving-heart-disease-in-men/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-08-12 13:47:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.