Artists painted in places where echoes and resonance created otherworldly sonic effects

Patrick Aventurier/Getty Images

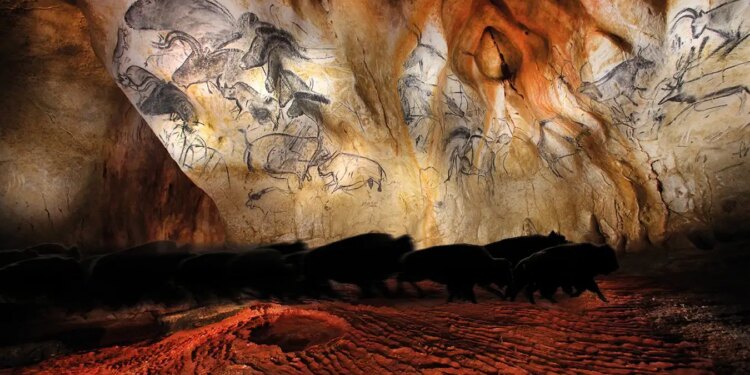

Deep underground, thousands of years of silence are abruptly broken by a researcher singing. His voice seems to awaken the walls of the cavern as the intimate space comes alive with the sound of our ancestors. Then he follows the cave’s resonant response, until the beam of his headlamp falls upon a panel of ancient paintings.

This crude experiment, performed decades ago, led to a remarkable discovery: that prehistoric rock art, created from 40,000 to 3,000 years ago, was meant to be heard as well as seen. “The oldest painted sites have this low, strange resonance, where if you sing, suddenly the cave sings back to you,” says Rupert Till at the University of Huddersfield, UK.

Getting solid scientific evidence to support this idea hasn’t been easy. Now, however, a seven-year study into the acoustic properties of rock art sites around the globe has provided it. The Artsoundscapes project leaves little doubt that prehistoric artists deliberately painted in places where echoes, resonance and sound transmission created otherworldly sonic effects. “I was completely amazed,” says archaeologist and project leader Margarita Díaz-Andreu at the University of Barcelona, Spain, recalling her experiments at Valltorta gorge in eastern Spain. “Before the paintings, there was barely any reverberation, but as soon as we reached the paintings, the sound changed immediately.”

And that’s just the start. By studying the peculiar soundscapes in which ancient artworks are embedded, Díaz-Andreu, Till and other archaeoacoustic researchers are beginning to reconstruct the ways in which these ancient, multisensory illustrations amplified the potency of prehistoric rituals, storytelling and shamanic musical performance – and, perhaps, even altered listeners’ states of consciousness.

Listening for echoes

That first researcher who used song to bring a new dimension to our understanding of Stone Age people was a French musicologist called Iégor Reznikoff, now a professor emeritus at Paris Nanterre University. He spent years vocalising inside palaeolithic caves in use from 18,000 to 11,000 years ago in his homeland before documenting his findings in the late 1980s. Counting the seconds between echoes, he noted a relationship between the placement of rock art and acoustic phenomena. “Iégor can go into a cave and make noises and guide you to rock art by listening for echoes,” says Till. “I’ve been into these caves with him.”

Reznikoff’s methods of talking to the walls lacked rigour, and his conclusions were largely ignored by archaeologists. But his ideas reverberated around the fringes of academia, where the emerging field of archaeoacoustics was struggling for recognition. Among the first to expand upon his findings was Steve Waller at the American Rock Art Research Association, who recorded echoes of up to 31 decibels at some decorated spots in deep caves in France, while unpainted walls in the same caverns were acoustically dead.

“

In deep caves, the echoes blur together like thunder, and it gives you this vision of a stampede of hoofed animals

“

“In deep caves, the echoes blur together like thunder, and it gives you this vision of a stampede of hoofed animals,” says Waller. Writing in Nature in 1993, he pointed out that more than 90 per cent of European rock art depicts hoofed mammals like horses and bison, and suggested that echoing caves might have been interpreted as the homes of the thunder gods, who were embodied by these stampeding beasts.

Two decades later, with archaeoacoustics still largely overlooked as a legitimate field, Till launched the Songs of the Caves project to study the acoustics of painted caverns in northern Spain. Rather than just timing the delay between echoes, he and his colleagues took a measurement called the impulse response, which entails quantifying the movement of sound waves through a space when a short, sharp sound is played to give a so-called sonic fingerprint. “We did 250-odd acoustic samples in the caves, both next to rock art and where there was no rock art,” says Till. “And we showed that there was a statistical relationship between the likelihood of there being a piece of rock art and an ‘unusual’ acoustic phenomenon that was associated with it.”

Around the same time, Díaz-Andreu began investigating the soundscapes at Stone Age sites across Europe, providing more nuanced insights into these acoustic relationships. In Spain’s Sierra de San Serván, for instance, she noted that art was predominantly found in rock shelters with “augmented audibility”. “This means that the places that had been chosen to be painted were those from which you could acoustically control the landscape,” she says. To give a sense of what this might mean, she recounts being able to hear a distant dog-walker’s phone conversation with astonishing clarity while standing at one of the decorated spots.

Although these findings helped to advance the field of archaeoacoustics, many scholars continued to regard it as a fringe discipline. So, in 2018, Díaz-Andreu initiated Artsoundscapes, which introduced cutting-edge methods to systematically measure sonic phenomena at painted sites across the world. Among the techniques pioneered by her team was the use of a dodecahedron featuring 12 loudspeakers to create a dynamic, omnidirectional impulse response. The researchers also used computerised models like geographic information systems to map the connections between rock art and acoustic effects.

Equipment used to measure acoustics in Cuevas de la Araña

N. Santos da Rosa

Since wrapping up the project earlier this year, the team has published a series of studies from sites across four continents. They reveal that prehistoric cultures around the world used sound in strikingly different ways. In Siberia’s Altai mountains, for example, amplification and unusually high clarity of sound were detected at potential gathering spots, where rituals and offerings involving music may once have taken place. In Mexico’s Santa Teresa canyon, there is rock art at sites where pre-Hispanic cultures are thought to have held ritual dances. And at Spain’s Cuevas de la Araña, the researchers report finding paintings primarily where the caves’ acoustics “could have intensified the sensory effect and emotional impact of ceremonies likely performed with musical accompaniment”.

The team also visited White River Narrows, a canyon in Nevada where Waller had previously noted an unusual sonic connection between painted rock faces. “Some of the rock art sites can actually communicate with each other, so if you’re at one, you can hear the echoing coming to you from another,” he says. Building on this, the Artsoundscapes researchers discovered that certain painted spaces outside the canyon lack reverberation but possess exceptional sound transmission, reproducing sounds with great clarity and amplification. Therefore, they concluded, these sites would have been more suitable for storytelling than shamanic rituals.

Only in South Africa’s Maloti-Drakensberg mountains – which are famous for their San rock art – did the team fail to find a connection between paintings and sound. “We were expecting fantastic results – something new and exciting,” says Díaz-Andreu. “We didn’t find them.”

Perceiving a “presence”

Although there is no universal pattern, there is a growing consensus that painted sites worldwide were often chosen for their extraordinary acoustic properties and the impact these would have had on people’s consciousness. In Finland’s lake district, for example, prehistoric hunter-gatherers were inspired to leave their mark on cliffs that produced a disorienting sonic reflection. “The [wall] repeats, or doubles, every sound that you make in front of it, so that you experience a kind of doubled reality that is not normal,” says Riitta Rainio at the University of Helsinki in Finland. “It’s not a long echo like in caves, but a single reflection that’s very short, sharp and strong.”

Rainio and her colleagues have conducted psychoacoustic experiments to measure the subjective response of modern listeners to this auditory illusion. They found that people tend to perceive a “presence” at these painted sites. In one recent paper, they wrote that the sounds seem to “emanate from invisible sources behind the paintings” and that “a prehistoric visitor, who marvelled at the voices, music, and noises emanating from the rock, would have recognised them as coming from a human-like source, perhaps some kind of apparition or living person inside the rock”.

Speaking of her own experiences at the lakeside rock faces, Rainio says: “I was often quite scared, because I really thought that there was someone else there. There’s this phenomenon where it seems like someone is approaching you as you approach the cliff.”

“

There’s this phenomenon where it seems like someone is approaching you as you approach the cliff

“

Similarly, the Artsoundscapes team has investigated the psychoacoustic impact of rock art sites in both Siberia and the Mediterranean. Using the impulse response data from decorated caves in the Altai mountains, the team created “auralizations” of natural sounds – including animal calls, weather phenomena and the crackling of a bonfire – as if heard from within these spaces. In laboratory tests, participants reported that these digitised soundscapes evoked feelings of “presence”, “closeness” and “tension”.

Teaming up with neuroscientists at the University of Barcelona’s Brainlab, Díaz-Andreu’s group also used electroencephalography (EEG) to study the ways in which certain sounds influence human brain activity. Their findings suggest that our brainwaves tend to synchronise with music that has a tempo of 99 beats per minute, potentially triggering altered states of consciousness. How this discovery relates to ancient shamanic rituals at rock art sites is a matter of conjecture, however. “We don’t know for sure what the meaning of those sites was, but they are generally regarded as sacred, religious or ritual places,” says Rainio. “And ritual usually means some kind of sound-making, which is often music.” Tellingly, some of the paintings in Finland depict people playing drums.

Prehistoric sounds

Another clue about the sorts of sounds prehistoric people made at these decorated rock faces comes from the painted Isturitz cave in France, where 35,000-year-old flutes made from vulture bones have been found. By playing replicas of these prehistoric instruments inside the caverns where they were discovered, Till became the first person since the Stone Age to experience their ritual potential. “Previously, I’d only ever heard these bone flutes in classrooms or in concert halls, where they have quite a polite sound, a small sound,” he says. “But then you take them into the cave and they produce this enormous, soaring sound, which transforms the cave into a space that sings.”

Listen: Vulture bone replica of the Hohle Fels flute being played by Anna Friedericke Potengowski in the Hohle Fels cave

![endif]–>

Similar experiments have been conducted by archaeologist Fernando Coimbra at the Portuguese Centre for Geohistory and Prehistory, who played replicas of ancient bone flutes at a palaeolithic rock art site called Escoural cave. “When I played songs outside the cave, the sound vanished, but inside, the cave acts as an amplifier,” he says.

In addition, archaeoacoustics researchers are moving beyond the sphere of rock art to reveal the many ways in which music may have shaped ancient ritual experiences. At the 5000-year-old Neolithic tomb of Ħal Saflieni in Malta, for instance, experiments by both Till and Coimbra have identified unusual resonant frequencies within a chamber called the oracle room. “If you play a large drum in there, the bass frequencies sustain for about 35 seconds, which is just remarkable”, says Till. “So, you have to think of Ħal Saflieni not as a place where music was played, but as a musical instrument in itself, because the resonances are so strong that if you play anything in there, the building rings.”

Listen: Iégor Reznikoff singing in the Hypogeum of Hal Saflieni

Inspired by similar, earlier findings, neuroscientists at the University of California, Los Angeles, used EEG to measure how these acoustic resonances affect human brain activity. Intriguingly, they discovered that frequencies close to 110 hertz – characteristic of a low baritone voice – tend to deactivate the brain’s language centres and may boost emotional processing within the prefrontal cortex. This supports the idea that ritual chanting at places like Ħal Saflieni may have altered the consciousness of people within the space.

Nevertheless, not everyone is convinced that these sites were deliberately engineered to produce such acoustic effects. A 3000-year-old temple in Peru, for instance, creates acoustic resonances at the same frequency as those produced by conch shell horns – or pututus – excavated at the site. “I don’t believe, personally, that the Chavín architecture was built simply to work with these conch shells,” says archaeoacoustic researcher Miriam Kolar at Stanford University in California. “But I’m convinced by the evidence that the relationship did not go unnoticed. It’s impossible to perform a pututu blast in any of the spaces of Chavín without getting some sort of strong sensory effect.”

We don’t know exactly what went on at the site, but Kolar says the “whole body response” triggered by these extraordinary acoustics may have provided a basis for ritual activities by creating a powerful shared experience. Likewise, Till’s archaeoacoustic research at Stonehenge in the UK suggests that the rhythmic sound of percussion would have “made the whole space resonate like a wine glass”, potentially synchronising the emotional experiences of thousands of participants during solstice rituals some 5000 years ago.

A temple in Peru produces acoustic resonances that match the frequency of conch shells found at the site

David Ryan/Alamy

Bringing the story full circle, Till thinks that these Neolithic monuments may have served to perpetuate the ritual function of Palaeolithic rock art sites. “We used to have caves where the spirits lived, and we knew the spirits lived there because we could hear their reverberation,” he says. “But when we left the caves to occupy the open spaces and the plains, we needed a place where the ancestors could be.” Stonehenge, Ħal Saflieni and other similar monuments may therefore have been built as new homes for the dead, where the voices of the spirits could once again be heard and consulted through sonic rituals.

This body of work is finally bringing archaeoacoustics into the fold of mainstream academia. More broadly, these findings underscore the importance of incorporating sound into archaeology, both in terms of enhancing our understanding of ancient ritual experiences and the conservation of prehistoric material culture. Waller points out that at famous rock art sites around the world, visitors are encouraged to exercise decorum and hush, yet until we reintroduce sound to these spaces, we won’t know what it is we are trying to protect.

“I’m advocating for the preservation of the sound, because there are examples where they’ve built a visitor centre right in the middle of the canyon or they’ve put the restroom right in front of the rock art panel, and they’re unintentionally ruining the acoustics,” he says.

“I’m trying to spread the word, to preserve the soundscapes.”

Topics:

Source link : https://www.newscientist.com/article/2502898-we-can-finally-hear-the-long-hidden-music-of-the-stone-age/?utm_campaign=RSS%7CNSNS&utm_source=NSNS&utm_medium=RSS&utm_content=home

Author :

Publish date : 2025-11-18 16:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.