BBC News, Nottingham

BBC

BBCThe NHS is largely funded by public money paid for through taxes and national insurance.

In February, one of the busiest and biggest NHS trusts in England was given a record £1.6m fine over maternity failings in connection with the deaths of three babies.

Nottingham University Hospitals (NUH) NHS trust is already at the centre of the largest maternity review of its kind in the NHS, following hundreds of baby deaths and injuries.

When it was fined at Nottingham Magistrates’ Court, the judge said the trust was operating at a deficit of about £100m, and added there was “no money to pay any substantial fines without requiring the trust to make further cuts”.

District Judge Grace Leong considered other court judgements and guidelines for comparable offences before handing down the fine.

So why was an already struggling, publicly-funded service given such a large fine, and what justice did the fine bring for the families the trust let down?

Emmie Studencki/Ryan Parker

Emmie Studencki/Ryan ParkerThe details of the case

Adele O’Sullivan died on 7 April 2021 – just 26 minutes old – Kahlani Rawson died on 15 June at four days old and Quinn Lias Parker died on 16 July at two days old.

NUH pleaded guilty to six counts of failing to provide safe care and treatment to the babies and their mothers, in a prosecution brought by the healthcare watchdog, the Care Quality Commission (CQC).

The court heard there were similar failings in all three cases, including a failure to expedite the delivery of the babies, not recognising serious conditions, communication issues and staff not being equipped to interpret anomalies in foetal heart monitoring.

It was the second time the trust had been prosecuted by the CQC for maternity failings.

Joe Giddens/PA Wire

Joe Giddens/PA WireIn 2023, the trust was fined £800,000 over the death of Wynter Andrews, who died shortly after her birth at the Queen’s Medical Centre in 2019.

Until this year, that fine was the largest handed down for maternity failings.

NUH prosecutions make up two of five maternity-related criminal prosecutions brought by the CQC.

The watchdog gained powers under the Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated activities) Regulations 2014, in 2015.

This prosecution by the CQC is separate from any prosecution that could arise from a corporate manslaughter investigation, which was opened earlier this month.

On 2 June, Nottinghamshire Police said it was examining whether maternity care provided by NUH had been grossly negligent.

How did the judge decide on £1.6m?

Google

GoogleIn her sentencing remarks, District Judge Grace Leong said she would have to fix a “significant financial penalty” to mark the gravity of the offences, but also had to strike “a delicate balance”.

“I cannot ignore the negative impact that the fine will have on services to patients at a time when the NHS continues to face unprecedented challenges both in terms of insufficient funding, the backlog of patients waiting for treatment and the demands placed upon the trust’s services from an ageing population,” the judge said.

There was no ceiling to the level of fine the judge could impose.

That meant the sentence was a matter of discretion, with the judge considering other sources of guidance – such as any High Court or Court of Appeal judgements – and other sentencing guidelines for comparable offences.

It was reduced from a starting point of £5.5m, as the judge took into account the financial implications on the public body and its guilty pleas.

How could the fine impact services?

NUH did not want to put anyone forward for interview, and did not wish to detail how the fine might impact services.

However, in response to the BBC, a statement from NUH chief executive Anthony May said: “We fully accept the findings from court, including the fine handed down by the judge.

“The mothers and families of these babies have had to endure things that no family should after the care provided by our hospitals failed them, and for that I am truly sorry.

“We will work to ensure to minimise the impact of the fine on our patients, including ongoing efforts to improve our maternity services.”

NUH

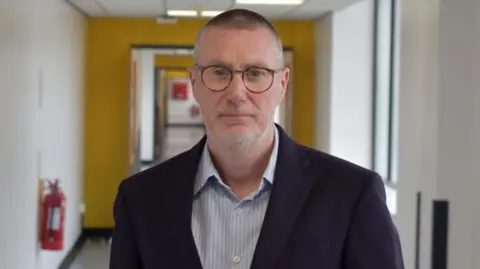

NUHRoy Lilley, former chairman of the old Homewood NHS Trust in Chertsey, Surrey – which later merged with Ashford and St. Peter’s Hospitals NHS Trust – and now an independent commentator on health service issues, said some impact on services would be “inevitable”.

“Clearly a chunk of money like £1.6m is going to have an impact on the trust’s ability to operate.

“The day-to-day running of the trust is, of course, difficult enough with all the financial pressures but to have this kind of money taken out of its revenue balances, it makes it even more difficult,” he said.

Mr Lilley – who has not worked for NUH – added: “It will certainly slow down some of the plans that they had in terms of improvements.”

“Generally it has a very bad effect, a big impact on the trust’s ability to respond,” he said.

Mr Lilley said it was possible for trusts to seek loans from the Department of Health of Social Care (DHSC) in the face of financial difficulty.

The BBC understands while NHS trusts are expected to meet their legal and financial obligations – including prosecution fines – they can access loans in some instances.

The trust’s annual budget is £1.8bn.

PA Media

PA MediaWhat does the fine mean to the families?

The families affected by NUH’s maternity failings have consistently called for accountability.

Following the sentencing, solicitor Natalie Cosgrave – representing the parents of baby Quinn – said in a statement that the prosecution was “the only system that exists” to obtain it.

Sadie Simpson, an associate clinical negligence solicitor who represented the families of Adele and Kahlani, told the BBC the trust’s guilty plea was “some level of accountability, but it’s only one part of a much bigger picture”.

To the bereaved families, it is individuals who should be held accountable, not just the trust as an organisation, Ms Simpson said.

Ms Simpson has also represented the families of Adele and Kahlani, as well as others, in civil claims against NUH.

At each stage of the various investigations and proceedings they have endured – including inquests, internal reviews and court hearings – the families have called for more change and scrutiny.

Ms Simpson said: “The judge was very clear that a fine is the only sentence that she can impose, and no fine is ever going to be enough when you’ve lost your child.”

During the sentencing in February, the earlier case of Wynter Andrews – who died 23 minutes after being born – was referenced several times.

Her parents Sarah and Gary Andrews watched the hearing from the public gallery “as concerned parents”, but did not know their daughter’s case would be mentioned “quite so prominently”.

“I think for us it’s important to highlight that this process is the only avenue that families have to get some accountability,” he said.

“The judge is in a really difficult position, I feel, but we’re counting pennies over babies’ lives.”

Where does the money go?

The fine is paid to HM Treasury – the government’s finance ministry which controls public spending – as with any prosecution fine.

Families affected in this case will not receive any of the money from the prosecution.

The trust was also told to cover prosecution costs of £67,755.23 and a victim surcharge of £190.

Prosecution costs in this case will be paid to the CQC.

The victim surcharge – which is imposed on offenders to ensure they hold some responsibility towards the cost of support victims and witnesses – goes to a general fund and not directly to those involved.

That money provides a contribution towards Ministry of Justice-funded support services for victims and witnesses.

The £1.6m fine is separate from the tens of millions of pounds the trust has paid out in damages for civil claims in relation to maternity care.

What next for the trust?

Nottinghamshire Police’s investigation into the trust’s maternity services – called Operation Perth – has seen more than 200 family cases referred to it so far.

Meanwhile, the separate maternity review by senior midwife Donna Ockenden is currently examining the testimony of more than 2,000 cases.

The review began in September 2022 and closed to new cases at the end of May.

Ms Ockenden’s final report of findings is due to be published in June 2026.

And last week, the trust announced plans to cut at least 430 jobs in an attempt to save £97m in the next year.

The planned job cuts follow the government’s instruction to all trusts to reduce the size of their corporate and support services, and were not as a result of the record fine, the trust said.

Source link : https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ckgrjr7emlgo

Author :

Publish date : 2025-06-20 05:25:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.